By Dan Callahan

[The Furies streets on June 24th, 2008. Screencaps from DVDBeaver.] Anthony Mann is best known today for the remarkable series of westerns he made with James Stewart in the fifties, but he reached his peak with Men in War (1957) and Man of the West (1958), late works which brought his central theme of the violence within man and the demoralizing aftermath of violence to nearly intolerable heights of insight and catharsis. In his famous Stewart films, Mann had a tendency to be a bit too tidy in his storytelling; coming out of one of his mid-period westerns can be a little like exiting a scrupulous, intelligent lecture on ethics and morality, festooned with some of the best landscape photography this side of John Ford. Criterion’s surprising, all-stops-out release of Mann’s early western The Furies (1950) offers a valuable view of this director nearing the height of his powers, before his gifts had calcified; in many ways, it’s his most exciting movie because it’s also his most unresolved, opening up a Pandora’s box of psychological issues that cannot be contained in any conventional conclusion.

Anthony Mann is best known today for the remarkable series of westerns he made with James Stewart in the fifties, but he reached his peak with Men in War (1957) and Man of the West (1958), late works which brought his central theme of the violence within man and the demoralizing aftermath of violence to nearly intolerable heights of insight and catharsis. In his famous Stewart films, Mann had a tendency to be a bit too tidy in his storytelling; coming out of one of his mid-period westerns can be a little like exiting a scrupulous, intelligent lecture on ethics and morality, festooned with some of the best landscape photography this side of John Ford. Criterion’s surprising, all-stops-out release of Mann’s early western The Furies (1950) offers a valuable view of this director nearing the height of his powers, before his gifts had calcified; in many ways, it’s his most exciting movie because it’s also his most unresolved, opening up a Pandora’s box of psychological issues that cannot be contained in any conventional conclusion.

At its core, The Furies is a passionate stand off between a father and a daughter, played by a rip-snorting Walter Huston (in his last role on screen) and a primal Barbara Stanwyck, who dazzlingly alternates between extreme aggression and extreme, childlike vulnerability. As T.C. Jeffords, a wily cattle baron who fancies himself a sort of prairie Napoleon, Huston is in titanic grand old man mold (if you want to see the real genesis of Daniel Day-Lewis’ John Huston-aping Daniel Plainview, look no further). His beady eyes twinkling, T.C. continually asks Vance to scratch his “sixth lumbar vertebrae,” and when you see the outrageously knowing way that Stanwyck scratches her Daddy’s itches, you’ll wonder how Mann snuck this Incest Out West epic past the censors. The Furies has several tributary plots, the most affecting of which is Vance’s platonic love affair with her best friend Juan (Gilbert Roland), a Mexican on the verge of being burned off his own land by her father. Stanwyck develops far more heat and feeling with Roland than with her nominal leading man, Wendell Corey, but the real face-off mid-way through the film is between Vance and a self-described “adventuress” played by the formidable Judith Anderson. In the theater, Anderson was the greatest modern Medea and had cornered the market on vengeance, so it’s quite appropriate when this vengeance is visited upon her in the film’s most shocking scene; I won’t spoil it for you, but let’s just say that Stanwyck is the first, best and ultimate Scissors Sister.

The Furies has several tributary plots, the most affecting of which is Vance’s platonic love affair with her best friend Juan (Gilbert Roland), a Mexican on the verge of being burned off his own land by her father. Stanwyck develops far more heat and feeling with Roland than with her nominal leading man, Wendell Corey, but the real face-off mid-way through the film is between Vance and a self-described “adventuress” played by the formidable Judith Anderson. In the theater, Anderson was the greatest modern Medea and had cornered the market on vengeance, so it’s quite appropriate when this vengeance is visited upon her in the film’s most shocking scene; I won’t spoil it for you, but let’s just say that Stanwyck is the first, best and ultimate Scissors Sister.

It would take a boatload of Freudian psychoanalysts to unpack all the psychosexual baggage on display in The Furies, all amplified by one of Franz Waxman’s stormiest scores; most of the film is so alarming, and Stanwyck’s Vance is so dedicatedly perverse, that it’s easy to shake off the last twenty minutes or so, which serve as a kind of valedictory for Huston the actor while smoothing out the rough edges of his crude tycoon character. Fascinating as Stanwyck and Huston are, though, in the end it’s Anderson who haunts the film. In her last scene, this former tigress rises to a level of regret that’s practically Shakespearian in its pathos and depth, matching Mann’s obsessive attempts to bring the form of classical tragedy to the western. Her suffering is echoed in the famous scene in Mann’s The Man from Laramie (1955) where James Stewart’s hand gets shot at point blank range, and the sickening scene in Man of the West where Julie London is forced to strip. Mann was always after the root of our worst impulses, and in The Furies, a very messy, provoking film, he came a little closer to those roots than he ever would again, even in the justly lauded movies of his maturity. Image/Sound/Extras: There’s been a meticulous clean-up of the image, especially in the many outdoor scenes played in soft, nearly out of focus grey half-light, and the sound is good, though there’s a bit of hiss on the track towards the end. There’s a brief interview with Mann himself, a touching interview with his daughter Nina, who emphasizes how personal his movies were, an excellent commentary track by Jim Kitses, and Niven Busch’s original novel, a lurid blueprint for the film where Juan is more clearly Vance’s lover. Best of all, there’s a superb essay by Robin Wood on Mann’s westerns and The Furies in particular. All in all, this is one of the essential DVD releases of the year.

Image/Sound/Extras: There’s been a meticulous clean-up of the image, especially in the many outdoor scenes played in soft, nearly out of focus grey half-light, and the sound is good, though there’s a bit of hiss on the track towards the end. There’s a brief interview with Mann himself, a touching interview with his daughter Nina, who emphasizes how personal his movies were, an excellent commentary track by Jim Kitses, and Niven Busch’s original novel, a lurid blueprint for the film where Juan is more clearly Vance’s lover. Best of all, there’s a superb essay by Robin Wood on Mann’s westerns and The Furies in particular. All in all, this is one of the essential DVD releases of the year.

_________________________________________________

House contributor Dan Callahan's writing has appeared in Slant Magazine, Bright Lights Film Journal and Senses of Cinema, among other publications.

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

The Criterion Collection #435 The Furies

The Criterion Collection #434: Classe Touse Risques

By Andrew Chan Until recently, Claude Sautet’s Classe Tous Risques was a long forgotten noir relic. A commercial flop in its own country, it was only released briefly in the U.S. in a dubbed version called The Big Risk before it fell completely out of sight. But thanks to a Rialto Pictures re-release in 2005, and the attraction of lead performances from stars most consider among the immortals, it has the air of a major new discovery. Following hopeless fugitive Lino Ventura as he sneaks his way from Milan to Paris with wife and children in tow, Sautet’s first major film adopts some of the mood and energy from American crime movies but—like a handful of French films before and after it—tries to endow the genre with a conscience. Responsibility to friends and family humanizes even the most heartless, and Classe Tous Risques takes as its subject the masculine codes of honor that are upheld and broken by those who dare to live outside the law.

Until recently, Claude Sautet’s Classe Tous Risques was a long forgotten noir relic. A commercial flop in its own country, it was only released briefly in the U.S. in a dubbed version called The Big Risk before it fell completely out of sight. But thanks to a Rialto Pictures re-release in 2005, and the attraction of lead performances from stars most consider among the immortals, it has the air of a major new discovery. Following hopeless fugitive Lino Ventura as he sneaks his way from Milan to Paris with wife and children in tow, Sautet’s first major film adopts some of the mood and energy from American crime movies but—like a handful of French films before and after it—tries to endow the genre with a conscience. Responsibility to friends and family humanizes even the most heartless, and Classe Tous Risques takes as its subject the masculine codes of honor that are upheld and broken by those who dare to live outside the law.

The rediscovery of Classe Tous Risques is, in a way, doubly special, as it leads us to reexamine the work of someone who is not an acknowledged master. Sautet’s career is notable for its lack of ostentation. Having begun as a highly respected assistant director in the ’50s, known for fixing the weak spots in a script and taking the reins from inept filmmakers (Truffaut once called him the “mender of French cinema”), he made a name for himself as a skilled and competent craftsman but not as an auteur. Against the two great superstars of the French New Wave, both of whom made their debuts right around the time Classe Tous Risques was released, he had neither the stylistic flair nor the youthful preoccupations to hold his own. What anchored his films was not the nouvelle vague’s cinephilia or ideology, but rather the ordinary human concerns he found at the center of big genre constructions like the criminal underworld or the comic ménage a trois. For him, even the fantasies of genre were subject to the cruel disappointments of real life. I can’t claim any special expertise on Sautet, having only seen the four titles (out of the 14 features he made) currently available on American DVD. But looking back at what I’ve seen of this unsung oeuvre, what strikes me are the affinities linking works as disparate as his first gangster film and the not-quite-romantic dramas for which he later became famous. Consider the lovely César and Rosalie, which was a hit for him in 1972, and the intriguingly understated, mostly unarticulated passion of Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud, which in 1995 became his swan song. Both films introduce an amiable, well-liked man in the autumn of his years falling in love with a young woman. Both are leisurely paced and visually sunny, but also characterized by midlife male frustration. This fascination with aging—with the male’s stumbling transition from one self to another, milder, less free self—can be found in Classe Tous Risques, where Ventura must face up to the responsibilities of a grown man just as the sins of his youth are catching up with him.

I can’t claim any special expertise on Sautet, having only seen the four titles (out of the 14 features he made) currently available on American DVD. But looking back at what I’ve seen of this unsung oeuvre, what strikes me are the affinities linking works as disparate as his first gangster film and the not-quite-romantic dramas for which he later became famous. Consider the lovely César and Rosalie, which was a hit for him in 1972, and the intriguingly understated, mostly unarticulated passion of Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud, which in 1995 became his swan song. Both films introduce an amiable, well-liked man in the autumn of his years falling in love with a young woman. Both are leisurely paced and visually sunny, but also characterized by midlife male frustration. This fascination with aging—with the male’s stumbling transition from one self to another, milder, less free self—can be found in Classe Tous Risques, where Ventura must face up to the responsibilities of a grown man just as the sins of his youth are catching up with him.

In contrast to the sympathy Sautet extends to the men in César and Nelly, the women (Romy Schneider and Emmanuelle Béart) remain about as enigmatic as the trio of female characters in Classe Tous Risques. Defined by the vagueness of their whims, they are gauzily emotional, steely and unknowable, as if Sautet were paralyzed by the thought of having to enter a woman’s psychology. Accordingly, the representations of and attitudes toward love in these films are uniformly ambivalent, and remarkable for being neither condescending to that emotion nor confined by its intensity. When Ventura—almost at the end of his rope—takes time to fall in love with some random chambermaid, the plot twist serves as nothing more than an evanescent moment of grace, requiring minimal dramatization and no further explanation. Even at the end, love is possible, though it is clear it won’t absolve anyone’s sins or compensate for the greatest human weaknesses. While Sautet’s films profess to be grounded in and conflicted over adult fears and dilemmas, there is still something inexplicably remote about them. In César and Rosalie, the lack of intimacy we feel toward the characters allows us to buy into the central love triangle’s frequent and absurd rearrangements. But in Classe Tous Risques’ case, this remove becomes an impediment, keeping the film just out of reach of the ranks of Touchez pas au grisbi, Rififi, and Bob le flambeur, even in the moments when it thrills and moves us. In the effort to avoid melodrama—a difficult act to pull off with those children in jeopardy—it sometimes feels stiff and stifled rather than suave. There is no scene here comparable to the grudging tenderness of Jean Gabin and his best friend sharing a hotel room, or the twinkle in Roger Duchesne’s eyes when he acts as a father figure to a duo of street kids—no scene that gives us a feel for the genuineness of the gangster’s heart of gold and the depth of his family crisis, while also revealing the thug’s capacity for brutishness.

While Sautet’s films profess to be grounded in and conflicted over adult fears and dilemmas, there is still something inexplicably remote about them. In César and Rosalie, the lack of intimacy we feel toward the characters allows us to buy into the central love triangle’s frequent and absurd rearrangements. But in Classe Tous Risques’ case, this remove becomes an impediment, keeping the film just out of reach of the ranks of Touchez pas au grisbi, Rififi, and Bob le flambeur, even in the moments when it thrills and moves us. In the effort to avoid melodrama—a difficult act to pull off with those children in jeopardy—it sometimes feels stiff and stifled rather than suave. There is no scene here comparable to the grudging tenderness of Jean Gabin and his best friend sharing a hotel room, or the twinkle in Roger Duchesne’s eyes when he acts as a father figure to a duo of street kids—no scene that gives us a feel for the genuineness of the gangster’s heart of gold and the depth of his family crisis, while also revealing the thug’s capacity for brutishness.

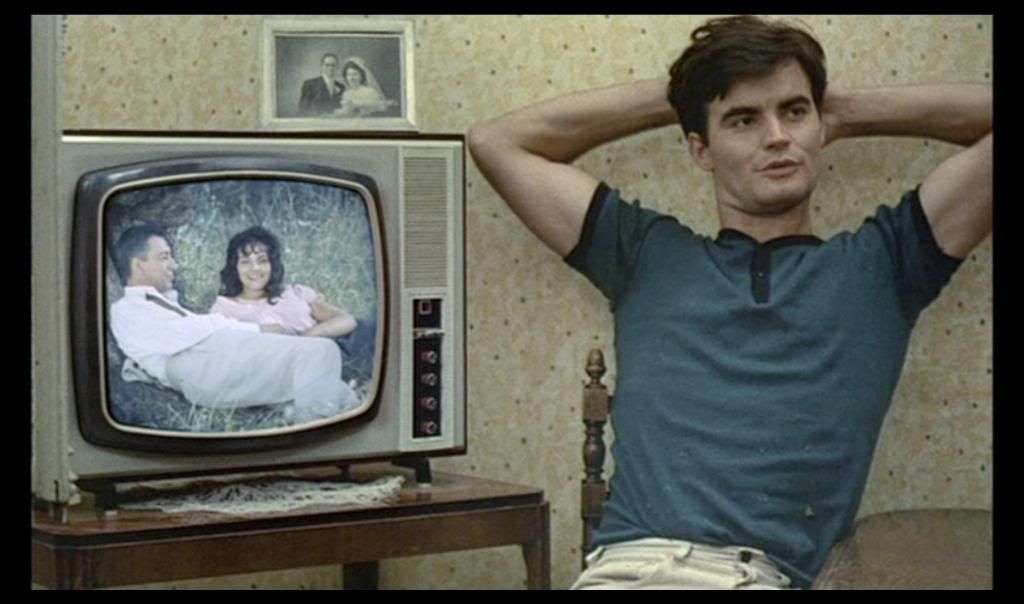

Ventura is great for his role and instantly relatable, his iconic face exuding more life-size decency than movie-size courage or charisma. But here he is largely incapable of communicating the sorrowfulness of a Bogart or the humor of a Gabin—qualities that make a cliché-ridden genre come alive with inner drama. It is Belmondo, with his mixture of toughness, seduction, and angelic innocence, who emerges as the film’s most alluring element, even as Sautet’s elliptical style keeps the character mostly inscrutable. As the hapless hero’s saving grace, Belmondo (fresh off a star-making turn in Breathless) offers the perfect foil to Ventura. More or less at peace with the contradictory extremes of criminal life, he’s as suave as any of the great men of noir, and separate from all the film’s middle-aged hand-wringing. Sautet’s vision was able to recognize human fragility without turning soft, and was willing to accept the ultimate dissatisfaction in relationships and social life. Where the rules of love fail the characters in Sautet’s later romances, the unforgiving nature of adult society and the irresoluteness of male friendship are what lead Ventura to his inescapable destiny. These darker, more personal undercurrents can easily go unnoticed when Classe Tous Risques is lumped with other pre-New Wave crime flicks, and when César and Nelly are marketed to appeal to the middle-brow tastes Truffaut famously ridiculed in his rants against “la qualité française,” along with the kind of movies that now get exiled to Blockbuster’s foreign section. If a director as subtle and sophisticated as Sautet still fails to inspire much excitement, it’s because he was always, in the words of Jonathan Rosenbaum, aesthetically conservative, even as he tried to breathe new life into tired old formulas. His Classe Tous Risques is not as cold-blooded or urgently told as the finest Hollywood noirs, or as boldly atmospheric as a Jean-Pierre Melville film, or even as entertaining as that wonderful Italian gangster comedy, Mafioso, just recently released on Criterion, which shares the same juxtaposition of the demands of domestic, private life with the relentless pull of the underworld.

Sautet’s vision was able to recognize human fragility without turning soft, and was willing to accept the ultimate dissatisfaction in relationships and social life. Where the rules of love fail the characters in Sautet’s later romances, the unforgiving nature of adult society and the irresoluteness of male friendship are what lead Ventura to his inescapable destiny. These darker, more personal undercurrents can easily go unnoticed when Classe Tous Risques is lumped with other pre-New Wave crime flicks, and when César and Nelly are marketed to appeal to the middle-brow tastes Truffaut famously ridiculed in his rants against “la qualité française,” along with the kind of movies that now get exiled to Blockbuster’s foreign section. If a director as subtle and sophisticated as Sautet still fails to inspire much excitement, it’s because he was always, in the words of Jonathan Rosenbaum, aesthetically conservative, even as he tried to breathe new life into tired old formulas. His Classe Tous Risques is not as cold-blooded or urgently told as the finest Hollywood noirs, or as boldly atmospheric as a Jean-Pierre Melville film, or even as entertaining as that wonderful Italian gangster comedy, Mafioso, just recently released on Criterion, which shares the same juxtaposition of the demands of domestic, private life with the relentless pull of the underworld.

But one trick that Sautet quietly pioneered in both Classe and his later romances is sure to leave a deep impression on anyone interested in taking a closer look at the parallels in his work. His great trademark is a harsh, clipped narrative brevity: deaths and separations and ends of relationships coming so unceremoniously, with so little fanfare, that they show us the swiftness with which life’s changes—and a film’s climax—can occur. In Sautet’s world, as in ours, people depart without warning, without proper goodbyes. And at the end of Classe Tous Risques, Ventura, too, has vanished like an afterthought of the camera, perhaps no luckier or more tragic than the rest of us.

Image/Sound/Extras: The Criterion Collection’s one-disc package boasts a typically beautiful transfer, as well as an impressive collection of excerpts from interviews conducted by French critic N.T. Binh. These include conversations with Sautet, who shares his early experiences in the film industry, and novelist and screenwriter José Giovanni, who relates the true story that inspired him to write Classe Tous Risques. Also included is an old interview of Ventura looking back on his career. Along with the highly informative essays in the set’s booklet—most notable of which is a tribute by Bertrand Tavernier, reminiscing on his double-friendship with mentors Sautet and Giovanni—these supplementary materials emphasize the close bonds forged during the filmmaking process, an insight that complements the film’s focus on the complicated loyalties of male relationships.

Andrew Chan is a poet and film critic currently studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the creator of the blog Movie Love.

The Criterion Collection #426: The Ice Storm

By Andrew Chan As an NYU-educated Taiwanese filmmaker, Ang Lee seemed to make it clear with his 1992 debut that his concerns were both Eastern and Western. Only a few years on the heels of Amy Tan’s bestselling The Joy Luck Club, Pushing Hands and its commercially successful follow-up, The Wedding Banquet -- two films which were mainstream in their temperament, but bold in their bilingualism -- inserted themselves into an environment increasingly hospitable to Asian-American immigrant narratives. These first films were among the very few of their time that were interested in seriously examining the ways in which Chinese and Westerners interact in today’s world, and it is difficult to know what Lee could have contributed to the stunted development of Asian-American cinema had he mined this subject further. Instead of maintaining the intimate, personal tone of what would later be dubbed as his “Father Knows Best” trilogy, Lee went on to balance his first three modestly made Chinese-language films with three prestigious English-language ones, surprising viewers with how seamlessly he assimilated into a diverse set of quintessentially Western milieus. Some regarded his choice of material as if it were an astonishing stunt, because while Europeans from Fritz Lang all the way down to Milos Forman had experienced great success in Hollywood, no Asian director in history had ever even attempted to embrace Americanization on quite this level. Though Hong Kong’s Peter Chan (The Love Letter) and mainlander Chen Kaige (Killing Me Softly) have subsequently tried to pull off their own breakthroughs, Lee remains the only contemporary Chinese filmmaker to have integrated completely into the American movie industry.

As an NYU-educated Taiwanese filmmaker, Ang Lee seemed to make it clear with his 1992 debut that his concerns were both Eastern and Western. Only a few years on the heels of Amy Tan’s bestselling The Joy Luck Club, Pushing Hands and its commercially successful follow-up, The Wedding Banquet -- two films which were mainstream in their temperament, but bold in their bilingualism -- inserted themselves into an environment increasingly hospitable to Asian-American immigrant narratives. These first films were among the very few of their time that were interested in seriously examining the ways in which Chinese and Westerners interact in today’s world, and it is difficult to know what Lee could have contributed to the stunted development of Asian-American cinema had he mined this subject further. Instead of maintaining the intimate, personal tone of what would later be dubbed as his “Father Knows Best” trilogy, Lee went on to balance his first three modestly made Chinese-language films with three prestigious English-language ones, surprising viewers with how seamlessly he assimilated into a diverse set of quintessentially Western milieus. Some regarded his choice of material as if it were an astonishing stunt, because while Europeans from Fritz Lang all the way down to Milos Forman had experienced great success in Hollywood, no Asian director in history had ever even attempted to embrace Americanization on quite this level. Though Hong Kong’s Peter Chan (The Love Letter) and mainlander Chen Kaige (Killing Me Softly) have subsequently tried to pull off their own breakthroughs, Lee remains the only contemporary Chinese filmmaker to have integrated completely into the American movie industry. Emerging just as the Taiwanese New Wave was making its greatest strides, inventing its own language, and committing itself to the exploration of national identity, Lee shed any association he might have had with the aims of his countrymen. He was either extremely wide-ranging in his genre tastes, or he was creating a career right out of a film-school textbook, aligning himself with Hollywood models such as screwball comedy (The Wedding Banquet), classy period pieces (Sense and Sensibility), and grim social satire (The Ice Storm). Though Lee’s work might seem too polite to be truly divisive, the path he has chosen has inspired varying reactions among critics in the U.S., a fact that has become more obvious with each new film he has made since the turn of the millennium. Among a growing number of American critics, the globalized nature of Lee’s oeuvre has been equated with a lack of coherent vision or distinctive style, those qualities supposedly necessary to any true auteur. Where once his versatility was mistaken for edginess (and seemed, at one point, to be unanimously praised), the way it has secured his Academy pedigree has come to mark him as a cultural dullard -- a fate sealed by the straitjacketed sexuality of Brokeback Mountain and the lukewarm critical response to his by-the-numbers Lust, Caution. Since the twin Oscar successes of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Brokeback solidified his status as one of the few celebrity directors of his generation, detractors have been more emboldened to dismiss him as a mere craftsman, a symbol for the regrettable confluence of the arthouse market with safe, mainstream taste.

Emerging just as the Taiwanese New Wave was making its greatest strides, inventing its own language, and committing itself to the exploration of national identity, Lee shed any association he might have had with the aims of his countrymen. He was either extremely wide-ranging in his genre tastes, or he was creating a career right out of a film-school textbook, aligning himself with Hollywood models such as screwball comedy (The Wedding Banquet), classy period pieces (Sense and Sensibility), and grim social satire (The Ice Storm). Though Lee’s work might seem too polite to be truly divisive, the path he has chosen has inspired varying reactions among critics in the U.S., a fact that has become more obvious with each new film he has made since the turn of the millennium. Among a growing number of American critics, the globalized nature of Lee’s oeuvre has been equated with a lack of coherent vision or distinctive style, those qualities supposedly necessary to any true auteur. Where once his versatility was mistaken for edginess (and seemed, at one point, to be unanimously praised), the way it has secured his Academy pedigree has come to mark him as a cultural dullard -- a fate sealed by the straitjacketed sexuality of Brokeback Mountain and the lukewarm critical response to his by-the-numbers Lust, Caution. Since the twin Oscar successes of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Brokeback solidified his status as one of the few celebrity directors of his generation, detractors have been more emboldened to dismiss him as a mere craftsman, a symbol for the regrettable confluence of the arthouse market with safe, mainstream taste.

Lee is, by now, a naturalized American both legally and artistically. Could it be that by embracing the aesthetic traditions and social issues of this country, he has, to a certain degree, sacrificed public recognition as an “artist”? Does this response have anything to do with our current investment in the notion of national cinemas, or an underlying expectation that foreign-born auteurs should honor the responsibility of filming their native lands into being? And how much does our bestowal of the label “artist” rely upon our ability to imagine the director deeply enmeshed in (and personally implicated by) the cultural specificities of his material? In a globalized age, where the discussion of a movie’s nationality has become as much of a critical focal point as issues of authorship were at auteurism’s birth, it seems true that Lee fascinates us as someone whose body of work is most accurately described as international, or (perhaps in his estimation) post-“nationality.” In his second English-language film, The Ice Storm, Lee makes his most ostentatious claim to culturally specific insight on American life. But a decade after the film’s release (which was largely ignored at the box office and year-end awards), it still feels like the most mechanical exercise of his hit-and-miss career. Part of the failure must be attributed to the narrative itself, which follows the typical dysfunctions of unhappy suburban families in 1973 Connecticut. Heavy-handed metaphors, frequently banal observations, and a bogus denouement can be blamed on Rick Moody, who wrote the novel on which the film is based, and James Schamus, the long-time Lee collaborator responsible for the Cannes-winning screenplay. But there’s something additionally off-putting about the film’s determined frigidity, its lack of aesthetic personality. What we recognize as skillfulness in the directing lies in its leanness, in the sense that not a moment of storytelling is going to waste; where Pushing Hands was flabby and overextended, The Ice Storm shows Lee maturing in his craft and paring down his approach. But as interested as the film is in the domestic sphere as a stage for private humiliation, there’s very little inner life on display here, and not much moral or emotional riskiness. How could the Moody novel -- famous for being passionate, embittered, and semi-autobiographical -- have been rendered so bloodless on the big screen?

In his second English-language film, The Ice Storm, Lee makes his most ostentatious claim to culturally specific insight on American life. But a decade after the film’s release (which was largely ignored at the box office and year-end awards), it still feels like the most mechanical exercise of his hit-and-miss career. Part of the failure must be attributed to the narrative itself, which follows the typical dysfunctions of unhappy suburban families in 1973 Connecticut. Heavy-handed metaphors, frequently banal observations, and a bogus denouement can be blamed on Rick Moody, who wrote the novel on which the film is based, and James Schamus, the long-time Lee collaborator responsible for the Cannes-winning screenplay. But there’s something additionally off-putting about the film’s determined frigidity, its lack of aesthetic personality. What we recognize as skillfulness in the directing lies in its leanness, in the sense that not a moment of storytelling is going to waste; where Pushing Hands was flabby and overextended, The Ice Storm shows Lee maturing in his craft and paring down his approach. But as interested as the film is in the domestic sphere as a stage for private humiliation, there’s very little inner life on display here, and not much moral or emotional riskiness. How could the Moody novel -- famous for being passionate, embittered, and semi-autobiographical -- have been rendered so bloodless on the big screen? The Ice Storm tries its best to identity itself with the dark heart of the early ’70s; it has the look of Boogie Nights and Almost Famous with all the exuberance (including the songs) scoured out. But, more than anything, it is unmistakably an artifact of the ’90s, a trendy dissection of upper-middle-class American values that will forever be linked to more entertaining works such as American Beauty and the TV series Picket Fences. Hell-bent on exposing raging libidos and lonely hearts underneath all the good breeding, the film divides a cast of WASPy veterans and soon-to-be-famous young actors into two families, both plagued by midlife crisis, extramarital sex, and the trials of puberty. Structured to give full impact to Lee’s juxtapositions of the older and younger generations, the film shows adults scrambling to adopt the freedoms of the hippie movement, and ending up looking no more grown-up than their lonely, sexually experimental kids. Early exposition builds toward the film’s second half, which chronicles the disintegration of the characters’ personal and social worlds during a night of bad weather. Lee’s reversal of the “Father Knows Best” trilogy’s filially pious representations of its elders is tempered by a conservative, fire-and-brimstone approach to morality. In an embarrassing, climactic invocation of the mythic, Nature exacts atonement for sexual sin and poor parenting, and an innocent is sacrificed in order to reaffirm the love underlying all familial relationships.

The Ice Storm tries its best to identity itself with the dark heart of the early ’70s; it has the look of Boogie Nights and Almost Famous with all the exuberance (including the songs) scoured out. But, more than anything, it is unmistakably an artifact of the ’90s, a trendy dissection of upper-middle-class American values that will forever be linked to more entertaining works such as American Beauty and the TV series Picket Fences. Hell-bent on exposing raging libidos and lonely hearts underneath all the good breeding, the film divides a cast of WASPy veterans and soon-to-be-famous young actors into two families, both plagued by midlife crisis, extramarital sex, and the trials of puberty. Structured to give full impact to Lee’s juxtapositions of the older and younger generations, the film shows adults scrambling to adopt the freedoms of the hippie movement, and ending up looking no more grown-up than their lonely, sexually experimental kids. Early exposition builds toward the film’s second half, which chronicles the disintegration of the characters’ personal and social worlds during a night of bad weather. Lee’s reversal of the “Father Knows Best” trilogy’s filially pious representations of its elders is tempered by a conservative, fire-and-brimstone approach to morality. In an embarrassing, climactic invocation of the mythic, Nature exacts atonement for sexual sin and poor parenting, and an innocent is sacrificed in order to reaffirm the love underlying all familial relationships. There is, admittedly, a certain beauty in the film’s pacing during its first half, in the matter-of-fact way it tries to inform us of the momentous transitions both the characters and the society are undergoing, and also in its avoidance of fetishizing period detail. But at some point the audience has the sensation of repeatedly being jerked forward and back. A framing device involving the Marvel comic Fantastic Four is introduced early on, rather heavy-handedly, only to disappear and then occasionally resurface for no apparent reason. The film’s social and political critique also falls by the wayside, relegated to brief glimpses of Nixon speeches on TV and fleeting mentions of Deep Throat, alternative religion, and the Vietnam War. Having eliminated almost every aspect that might be considered peripheral, Lee maintains a tight focus on the two families, and yet all of the characters remain emotionally mysterious to us. While admirers of the film usually point to the ensemble cast as one of its main virtues, it’s difficult to look past how the majority of the lead performances rely on the same tics and tendencies on which many of these actors have built their entire careers. In the roles of the wives, Joan Allen is frozen in the wounded sternness that has been her shtick for years, while Sigourney Weaver spends her scenes with her best mean face on, lips pursed, fumbling the delivery of her bitchiest lines. As the philandering husband, Kevin Kline puts so much effort into blending the comic and the tragic, the sympathetic and the repugnant, that he ends up a blur. The children turn out to be even harder to tolerate: Christina Ricci plays morbid and sardonic, Elijah Wood is doe-eyed, and Tobey Maguire unleashes the endearing, introverted nerdiness he would use in the Spider-Man movies. When the unsung Jamey Sheridan, as a bereaved father, finally beats the diva-thespians at their own game by delivering the kind of emotional authenticity that cannot be faked, it feels as if he has wandered in off another set.

There is, admittedly, a certain beauty in the film’s pacing during its first half, in the matter-of-fact way it tries to inform us of the momentous transitions both the characters and the society are undergoing, and also in its avoidance of fetishizing period detail. But at some point the audience has the sensation of repeatedly being jerked forward and back. A framing device involving the Marvel comic Fantastic Four is introduced early on, rather heavy-handedly, only to disappear and then occasionally resurface for no apparent reason. The film’s social and political critique also falls by the wayside, relegated to brief glimpses of Nixon speeches on TV and fleeting mentions of Deep Throat, alternative religion, and the Vietnam War. Having eliminated almost every aspect that might be considered peripheral, Lee maintains a tight focus on the two families, and yet all of the characters remain emotionally mysterious to us. While admirers of the film usually point to the ensemble cast as one of its main virtues, it’s difficult to look past how the majority of the lead performances rely on the same tics and tendencies on which many of these actors have built their entire careers. In the roles of the wives, Joan Allen is frozen in the wounded sternness that has been her shtick for years, while Sigourney Weaver spends her scenes with her best mean face on, lips pursed, fumbling the delivery of her bitchiest lines. As the philandering husband, Kevin Kline puts so much effort into blending the comic and the tragic, the sympathetic and the repugnant, that he ends up a blur. The children turn out to be even harder to tolerate: Christina Ricci plays morbid and sardonic, Elijah Wood is doe-eyed, and Tobey Maguire unleashes the endearing, introverted nerdiness he would use in the Spider-Man movies. When the unsung Jamey Sheridan, as a bereaved father, finally beats the diva-thespians at their own game by delivering the kind of emotional authenticity that cannot be faked, it feels as if he has wandered in off another set.

In the late ’40s and early ’50s, the triumvirate of Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Arthur Miller depicted families going down in flames on a grand, tragic scale. American theater of that period set a new tone for the way we think about family dysfunction, producing what are still perhaps the nation’s most unsettling artistic explorations of the subject. Lee’s film is the aesthetic opposite of that tradition; austere rather than histrionic, self-consciously subdued rather than cathartic, its tone (not to mention its recurring train imagery) invites some viewers to make a false comparison to the serenity of Ozu. On the one hand, we can be grateful that The Ice Storm not only steers clear of what has become clichéd in great American drama, but that it also never falls prey to the irony that would make American Beauty so popular two years later (and would soon become the dominant tone for dark family portraits in American movies). In better hands, though, the film’s chilly disposition could have had the brutal yet poignant effect of Raymond Carver minimalism; instead it manages to make the clinical feel gratuitous, as if Lee were using Ordinary People as his model. In comparison to the warm humanism that characterizes the best of his work, the coldness immediately registers as an affectation, making the final plot twist’s attempt at tragedy all the more feeble and calculated. Though it’s impossible to know if the tepidness of this film has anything to do with Lee’s status (at the time) as a newcomer to America, one can’t help but note that its distance and disinterestedness fit alongside certain conceptions of that status. As in the work of another American-educated Taiwanese filmmaker, Edward Yang, The Ice Storm has an all-encompassing sympathy for both sides of the generational divide, a quality one might mistake for objectivity; what it lacks is Yang’s depth. Since he started making films in the English language, Lee has continually tried to disappear into his work, to render his own voice inconsequential -- an approach that flies in the face of auteurist values but is not, in itself, illegitimate. Despite this, it still seems that seeing America through the eyes of an immigrant should bring us some sort of new information about ourselves, new ways of evaluating our culture; at the very least, it shouldn’t make us even more bored of our own problems. But when the method is as culturally non-specific and stubbornly universalizing as Lee’s is both here and elsewhere, we end up reverting to the same old clichés about America, the world, and human nature.

Though it’s impossible to know if the tepidness of this film has anything to do with Lee’s status (at the time) as a newcomer to America, one can’t help but note that its distance and disinterestedness fit alongside certain conceptions of that status. As in the work of another American-educated Taiwanese filmmaker, Edward Yang, The Ice Storm has an all-encompassing sympathy for both sides of the generational divide, a quality one might mistake for objectivity; what it lacks is Yang’s depth. Since he started making films in the English language, Lee has continually tried to disappear into his work, to render his own voice inconsequential -- an approach that flies in the face of auteurist values but is not, in itself, illegitimate. Despite this, it still seems that seeing America through the eyes of an immigrant should bring us some sort of new information about ourselves, new ways of evaluating our culture; at the very least, it shouldn’t make us even more bored of our own problems. But when the method is as culturally non-specific and stubbornly universalizing as Lee’s is both here and elsewhere, we end up reverting to the same old clichés about America, the world, and human nature.

Images/Sound/Extras: While The Ice Storm may not warrant Criterion canonization (the cover goes so far as to proclaim it “one of the finest films of the nineties”), the new two-disc set makes the best possible case for the film in its extensive and informative supplemental material. Lee is not known for his electrifying personality, but the extras reveal his interesting and conscientious mind for cinema. A commentary featuring Lee and producer-screenwriter James Schamus begins with a good-natured “fuck you” to the question of how a Taiwanese director can make a movie about Americans. The lively discussion gives fans a chance to listen to their friendly rapport, which has been the basis for one of contemporary cinema’s most successful and enduring film collaborations. Other features include deleted scenes; a documentary of (mostly dull) reminiscences from the cast; interviews with the cinematographer, production designer, and costume designer; and a recent conversation between Lee and Schamus at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image. All this, in addition to an excellent transfer and Criterion’s best cover design so far this year, makes for a handsome (if not quite extraordinary) set.

Andrew Chan is a poet and film critic currently studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the creator of the blog Movie Love.

The Criterion Collection #422: The Last Emperor

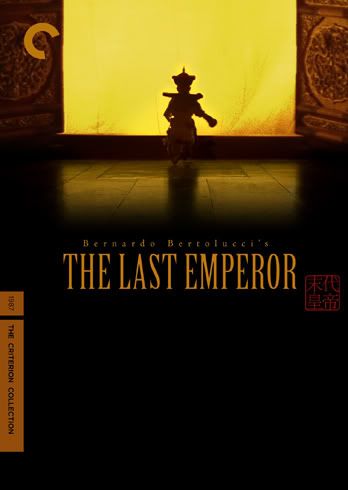

By Andrew Chan Before the average person could afford to travel by air, movies were the most viable form of transportation. Audiences were stunned by how this new medium could convince the eye it was having an intimate encounter with a corner of the world previously inaccessible. It is dismaying, then, to realize that a certain stock of images have always dominated cinema history, and that the art form so rarely lives up to its capacity for introducing new sights and sounds to our worldview. In the 1980s, when the Chinese government granted Bernardo Bertolucci unprecedented access to the Forbidden City, an entire nation that had been ignored in popular world cinema suddenly became a new frontier for Western viewers. The promise of the project must have seemed overwhelming: at a time when good old camp like The Good Earth and Shanghai Express were still Hollywood’s paradigmatic depictions of the country, here was the most sensual of European masters taking on the role of a modern-day Marco Polo. He would come back to share with us treasures that had never appeared before on a movie screen. When the resulting achievement, The Last Emperor, became an international hit and a whirlwind success at the Academy Awards, it was a breakthrough for Chinese images in Western cinema. But behind the silk veils and looming structures of Bertolucci’s biggest blockbuster remains one of the strangest mainstream epics imaginable, a film that wears its compromises of style and perspective on its sleeve.

Before the average person could afford to travel by air, movies were the most viable form of transportation. Audiences were stunned by how this new medium could convince the eye it was having an intimate encounter with a corner of the world previously inaccessible. It is dismaying, then, to realize that a certain stock of images have always dominated cinema history, and that the art form so rarely lives up to its capacity for introducing new sights and sounds to our worldview. In the 1980s, when the Chinese government granted Bernardo Bertolucci unprecedented access to the Forbidden City, an entire nation that had been ignored in popular world cinema suddenly became a new frontier for Western viewers. The promise of the project must have seemed overwhelming: at a time when good old camp like The Good Earth and Shanghai Express were still Hollywood’s paradigmatic depictions of the country, here was the most sensual of European masters taking on the role of a modern-day Marco Polo. He would come back to share with us treasures that had never appeared before on a movie screen. When the resulting achievement, The Last Emperor, became an international hit and a whirlwind success at the Academy Awards, it was a breakthrough for Chinese images in Western cinema. But behind the silk veils and looming structures of Bertolucci’s biggest blockbuster remains one of the strangest mainstream epics imaginable, a film that wears its compromises of style and perspective on its sleeve. Following the life of Pu Yi, who ascended the throne at the age of three, the film’s structure shifts back and forth from his early days as a purely symbolic ruler to his gradual movement away from the palace and later imprisonment in a Communist reeducation center. Doted on since infancy by eunuch servants who obey his every command, Pu Yi learns to live a life of seemingly unlimited privileges, but realizes he is trapped when he cannot even leave the grounds to mourn his biological mother who has died beyond the palace walls. Having never been instilled as a youth with any values other than that of his own (ultimately hollow) importance, he grows into little more than a marker of the times, a vessel for the ideologies he assumes in order to stay in power at least in name. He eventually falls prey to Japan, which establishes him as ruler of the puppet-state Manchuria.

Following the life of Pu Yi, who ascended the throne at the age of three, the film’s structure shifts back and forth from his early days as a purely symbolic ruler to his gradual movement away from the palace and later imprisonment in a Communist reeducation center. Doted on since infancy by eunuch servants who obey his every command, Pu Yi learns to live a life of seemingly unlimited privileges, but realizes he is trapped when he cannot even leave the grounds to mourn his biological mother who has died beyond the palace walls. Having never been instilled as a youth with any values other than that of his own (ultimately hollow) importance, he grows into little more than a marker of the times, a vessel for the ideologies he assumes in order to stay in power at least in name. He eventually falls prey to Japan, which establishes him as ruler of the puppet-state Manchuria.

The challenge of the film is to dramatize the struggle of a man who has little courage or wisdom to impress an audience, a man who was revered in his own cocoon-like remnant of China’s dying feudalist system, and who had only ever possessed the mere image of authority. Bertolucci doesn’t paint a portrait of a sympathetic or passionate person, so he is lucky to have chosen John Lone as the leading man. Playing Pu Yi from young adulthood to old age, and aided by some expert and subtle makeup work, Lone delivers the film’s most emotionally resonant performance by making variations on an unwavering emotional monotone. With more resignation than externalized despair, he manages to shape a character of compelling humanity and compromised dignity, communicating through perfectly maneuvered facial expressions (wounded but never pitiable). The title character is a cipher, but the restrained elegance of Lone’s interpretation helps anchor a film that insists on virtuosity on every sensory level. From the moment it enters the Forbidden City, the film dares us to take in all the beauty Bertolucci has laid out for us. It is as if he believes these long-storied palaces and courtyards were constructed for the sole purpose of being filmed by him. But The Last Emperor is not only a magnificent example of location shooting; it also counts as one of the great collaborations of cinematographer, art director, and costume designer, that relationship which has always been holy in the tradition of epic filmmaking. This is lavishness that doesn’t normalize; there is always something new to be awed by, which may be compensation for the absence of other traditional epic tropes that hook a viewer. There is no sweeping romance to speak of here, and the sex in the film is a collection of recycled gestures from The Conformist. Nor is there any suspense to relish in the film’s political intrigue, nor the epic’s usual expansive sense of space in the sets’ imprisoning enclosures.

The title character is a cipher, but the restrained elegance of Lone’s interpretation helps anchor a film that insists on virtuosity on every sensory level. From the moment it enters the Forbidden City, the film dares us to take in all the beauty Bertolucci has laid out for us. It is as if he believes these long-storied palaces and courtyards were constructed for the sole purpose of being filmed by him. But The Last Emperor is not only a magnificent example of location shooting; it also counts as one of the great collaborations of cinematographer, art director, and costume designer, that relationship which has always been holy in the tradition of epic filmmaking. This is lavishness that doesn’t normalize; there is always something new to be awed by, which may be compensation for the absence of other traditional epic tropes that hook a viewer. There is no sweeping romance to speak of here, and the sex in the film is a collection of recycled gestures from The Conformist. Nor is there any suspense to relish in the film’s political intrigue, nor the epic’s usual expansive sense of space in the sets’ imprisoning enclosures.

Banking on keeping the audience’s attention with the newness of its images, The Last Emperor is caught in the awkward position of having to reconcile its orientalist curiosity with its historical reverence, its markedly Western perspective with its desire to immerse audiences in authentic details of an insular world. What results from Bertolucci grafting his European sensibilities onto these Chinese landscapes? First off, it’s important to discuss the disorienting effect of having a predominantly Chinese cast deliver dialogue almost exclusively in English—an issue that is easier to raise now that a number of recent, popular American movies have been made in foreign languages (Letters from Iwo Jima, The Kite Runner). This choice emphasizes the alien quality that Bertolucci surrounds his characters in; for instance, the youngest versions of Pu Yi that we encounter in the film sound downright supernatural when they open their mouths and deliver the script’s stilted lines in vaguely Chinese-American accents. The strategy is full of pitfalls, and the wheels seem to come off completely when the emperor’s Scottish tutor arrives and, suddenly, the adolescent Pu Yi’s English becomes shakier as if to remind us that this is not his native language. But where a film like Memoirs of a Geisha was offensive for its substitution of Japanese with broken English, The Last Emperor is uncomfortable with a purpose, as it constantly keeps us aware that this interpretation of history is being translated through an outsider’s lens. At the same time, though, this reading of the film reveals one of the deepest flaws in screenwriter Mark Peploe’s writing: rarely escaping the caricatured cadence of their speech, all his characters remain merely conceptual and almost indistinguishable from each other in personality. Language is only one factor in the film’s negotiation of East and West. That struggle is embedded in Bertolucci’s exoticizing gaze, which never fails to relish the details of palace customs, such as a turtle swimming in a bowl of soup or a dance by Tibetan lamas. It is not Bertolucci’s goal to get us acclimated to our surroundings; at times, the Forbidden City is shot like a busily designed sci-fi/fantasy set, turning foreign style into gaudy artifice. But this is a film that makes a case for the exoticizing gaze as a mode native to the movie camera, and for exoticism as a natural interest of the cinema, insofar as the act of filmmaking is tied to the creation of spectacle. In its position in the chronology of film history (predating Zhang Yimou’s 1990 Ju Dou, the first mainland Chinese film to be nominated for a foreign-language Oscar), there is no way for The Last Emperor to dissociate from notions of the “exotic.” But the perspective from which it regards the Forbidden City seems accurate not only to the way foreigners would view it, but also to the way Chinese people are encouraged to view their own history—as a tourist attraction or amusement park—in the wake of headlong modernization. The changes that have occurred in twentieth-century China have occurred at such a speed that it is impossible for the splendors of the past to appear anything but alien to the contemporary experience. In the end, it is a double-edged sword that the film keeps the beast of Chinese history (rather than East-West relations) at the center of its attention. While this focus is a rare achievement for Western cinema, it also seems to have struck fear in the screenwriter, who seems intimidated by his own material, or by all the visual magicians bringing it to life along with him. Instead of offering us some much-needed characterization, Peploe substitutes the kind of existential numbness he brought to Antonioni’s The Passenger.

Language is only one factor in the film’s negotiation of East and West. That struggle is embedded in Bertolucci’s exoticizing gaze, which never fails to relish the details of palace customs, such as a turtle swimming in a bowl of soup or a dance by Tibetan lamas. It is not Bertolucci’s goal to get us acclimated to our surroundings; at times, the Forbidden City is shot like a busily designed sci-fi/fantasy set, turning foreign style into gaudy artifice. But this is a film that makes a case for the exoticizing gaze as a mode native to the movie camera, and for exoticism as a natural interest of the cinema, insofar as the act of filmmaking is tied to the creation of spectacle. In its position in the chronology of film history (predating Zhang Yimou’s 1990 Ju Dou, the first mainland Chinese film to be nominated for a foreign-language Oscar), there is no way for The Last Emperor to dissociate from notions of the “exotic.” But the perspective from which it regards the Forbidden City seems accurate not only to the way foreigners would view it, but also to the way Chinese people are encouraged to view their own history—as a tourist attraction or amusement park—in the wake of headlong modernization. The changes that have occurred in twentieth-century China have occurred at such a speed that it is impossible for the splendors of the past to appear anything but alien to the contemporary experience. In the end, it is a double-edged sword that the film keeps the beast of Chinese history (rather than East-West relations) at the center of its attention. While this focus is a rare achievement for Western cinema, it also seems to have struck fear in the screenwriter, who seems intimidated by his own material, or by all the visual magicians bringing it to life along with him. Instead of offering us some much-needed characterization, Peploe substitutes the kind of existential numbness he brought to Antonioni’s The Passenger.

The Last Emperor stands alongside Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi as a hugely popular ’80s film by a Western director in awe of Asia. Both of these biopics (and their runaway Oscar success) constituted a new kind of prestige picture, one that stroked the viewer’s self-regard by having him re-embrace the outside world but that also encouraged an aloof reaction with an enigmatic figure at its center. That Bertolucci’s film has always been the superior work is not only due to the visual genius on display in every frame. It is also because, in the end, it claims no authority over the history and culture it shares with us. Skimming the surface of the mind-boggling complexities of Chinese history, The Last Emperor can be both criticized and praised for the dissatisfaction it leaves in its audience. This is a film that seeks to engage that suspension of belief required by the most radical social upheavals, to inhabit that liminal space of historical transition. So perhaps it is right that Bertolucci would plant us behind a gauzy curtain rather than on the solid ground of the straightforward epic—even when such honorable distance is at times the film’s undoing.

Image/Sound/Extras: It would be hard to imagine a more satisfying treat for a Last Emperor and/or Bertolucci fan than Criterion’s new four-disc package. The company has outdone itself with a level of meticulousness and generosity rarely lavished on a single movie, and it’s difficult to think of a film more appropriate for such a comprehensive treatment. Despite being deeply flawed, Bertolucci’s most widely seen film deserves our continued attention and fascination for the ways in which it foregrounds almost every element of old-fashioned movie magic. Encountering the film in this beautiful edition, one is left with little question as to how it swept all the technical Oscars of its year. Two major issues surround this release. Disc 1 presents the 165-minute cut seen in theaters in 1987, while Disc 2 offers the television version (which is 53 minutes longer). In a statement on the Criterion blog, the DVD’s producer, Kim Hendrickson, corrects the assumption that the TV version is the “director’s cut” (as it has been promoted on the previous Artisan DVD) and shares a correspondence with the director in which he admits to finding the longer cut “not much different from the other one, just a little more boring.” The TV version was originally completed to fulfill a contractual obligation, but Bertolucci has always considered the theatrical release as definitive. Evaluating the two versions side by side, though, reveals what several critics (including myself) have felt: that the longer cut is the richer experience. While it doesn’t add much in terms of narrative (except for additional prison scenes and one minor character) or historical depth, it smoothes out many of the transitions that seem jerky in the theatrical version, and makes certain scenes more resonant simply by extending them.

Two major issues surround this release. Disc 1 presents the 165-minute cut seen in theaters in 1987, while Disc 2 offers the television version (which is 53 minutes longer). In a statement on the Criterion blog, the DVD’s producer, Kim Hendrickson, corrects the assumption that the TV version is the “director’s cut” (as it has been promoted on the previous Artisan DVD) and shares a correspondence with the director in which he admits to finding the longer cut “not much different from the other one, just a little more boring.” The TV version was originally completed to fulfill a contractual obligation, but Bertolucci has always considered the theatrical release as definitive. Evaluating the two versions side by side, though, reveals what several critics (including myself) have felt: that the longer cut is the richer experience. While it doesn’t add much in terms of narrative (except for additional prison scenes and one minor character) or historical depth, it smoothes out many of the transitions that seem jerky in the theatrical version, and makes certain scenes more resonant simply by extending them.

The more controversial point that must be raised about this DVD regards the involvement of Storaro, who overlooked and approved the transfer. As has been discussed in detail already on a number of DVD review sites, the cinematographer has tried to unify the aspect ratios of his films with the 2.00:1 format Univision, which he devised in 1998 out of fear that his images would be compromised on TV screens. I have not been able to compare Last Emperor’s original 2.35:1 frame with this cropped version, nor do I consider myself a strict purist, but—as many film enthusiasts have noted—home viewing has changed a lot in the decade since Storaro raised his concerns. That this legendary cinematographer (certainly one of the cinema’s great living visual stylists) would retroactively mutilate his own compositions is not a choice easily sympathized with, even if his Univision format once seemed a practical solution to a real problem. However, according to Criterion’s most recent statement on the issue, the original aspect ratio was wider than intended, and 2:1 was always Storaro’s ideal. The cropping isn’t likely to distract most viewers, though, since the image quality on Disc 1 seems to me almost flawless (though it is considerably grainier on Disc 2), and the transfer is a vast improvement on the abysmal Artisan release that has circulated since 1999. The last two discs compile an overwhelming array of supplemental material, which together work to dramatize the process of epic filmmaking to greater effect than almost any other set of DVD features I can think of. Four lengthy featurettes cover a wide terrain. "The Italian Traveler" engages Bertolucci the visionary, featuring him philosophizing on the voiceover, and chronicling his movement East after his proposed adaptation of Dashiel Hammett’s Red Harvest fell through. Two other hour-long documentaries (one produced by BBC) follow the making of the film and offer some incredible behind-the-scenes moments, including footage of Gabriella Cristiana discussing editing choices with Bertolucci. The most recent of the four featurettes is a new collection of interviews with the film’s cinematographer, art director, costume designer, and editor, reminiscing in great detail on their Oscar-winning labors. Rounding out the set is a preproduction video of Chinese locations, which gives viewers a portrait of the country as it looked in the late ’80s, and a handful of interviews that provide insight into the historical background and the artistic process behind the film.

The last two discs compile an overwhelming array of supplemental material, which together work to dramatize the process of epic filmmaking to greater effect than almost any other set of DVD features I can think of. Four lengthy featurettes cover a wide terrain. "The Italian Traveler" engages Bertolucci the visionary, featuring him philosophizing on the voiceover, and chronicling his movement East after his proposed adaptation of Dashiel Hammett’s Red Harvest fell through. Two other hour-long documentaries (one produced by BBC) follow the making of the film and offer some incredible behind-the-scenes moments, including footage of Gabriella Cristiana discussing editing choices with Bertolucci. The most recent of the four featurettes is a new collection of interviews with the film’s cinematographer, art director, costume designer, and editor, reminiscing in great detail on their Oscar-winning labors. Rounding out the set is a preproduction video of Chinese locations, which gives viewers a portrait of the country as it looked in the late ’80s, and a handful of interviews that provide insight into the historical background and the artistic process behind the film.

One of the treasures of this set is a commentary featuring Bertolucci, Jeremy Thomas, screenwriter Mark Peploe, and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto. Running the entire length of the theatrical version, the talk could easily have become boring, but the reminiscences from all participants are instead uniformly entertaining. Another gem in the box is an elegant 96-page booklet, with David Thomson’s astute appreciation of the film as exemplary “tourist cinema,” a brief but deeply felt Film Comment article written by Bertolucci, interviews with Ferdinando Scarfiotti and actor Ying Ruocheng, and a piece by Bertolucci’s personal assistant, followed by his shooting diary. What is extraordinary about Criterion’s work here is that the wealth of extras does not overwhelm or overstate the value of The Last Emperor. Instead, it elaborates on what is indisputably brilliant and interesting in the movie (its visual splendor; its reflection of a certain historical and aesthetic moment), and offers a balanced portrait of a kind of filmmaking that is both auteur-driven and highly collaborative.

Andrew Chan is a poet and film critic currently studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the creator of the blog Movie Love.

The Criterion Collection #421: Pierrot le fou

“A film is like a battleground. It has love… hate… action… violence… death… in one word, emotions.”

True, that is what Samuel Fuller famously declares early on in Pierrot le fou as his definition of cinema. But while Jean-Luc Godard’s 1965 feature certainly has those first five components contained within its wildly free-form structure, emotions aren’t exactly in abundance here. Or, to put it more accurately, there are emotions, but those emotions are deconstructed and examined to the point that standard reactions to such moments no longer apply. How you are supposed to feel about the plot and the characters in the film remains frustratingly elusive—and perhaps, in the end, irrelevant. Pierrot le fou is quite possibly the “movie-about-movies” par excellence, because by the end of it those moments of love, hate, action, violence and death don’t matter so much as one’s own unsettled awareness of just how familiar and concrete movie emotions—especially those within the kinds of genre films often adored by Godard and his Cahiers du cinéma peers—often seem compared to the messier and more complex emotions one encounters in real life.

True, that is what Samuel Fuller famously declares early on in Pierrot le fou as his definition of cinema. But while Jean-Luc Godard’s 1965 feature certainly has those first five components contained within its wildly free-form structure, emotions aren’t exactly in abundance here. Or, to put it more accurately, there are emotions, but those emotions are deconstructed and examined to the point that standard reactions to such moments no longer apply. How you are supposed to feel about the plot and the characters in the film remains frustratingly elusive—and perhaps, in the end, irrelevant. Pierrot le fou is quite possibly the “movie-about-movies” par excellence, because by the end of it those moments of love, hate, action, violence and death don’t matter so much as one’s own unsettled awareness of just how familiar and concrete movie emotions—especially those within the kinds of genre films often adored by Godard and his Cahiers du cinéma peers—often seem compared to the messier and more complex emotions one encounters in real life.Thus, the heart of this seminal Godard work lies not so much in its “last romantic couple,” not in Raoul Coutard’s eye-popping color cinematography (capturing both privilege and freedom in lush comic-book colors), not even in its many plot twists and tonal and genre shifts. All of these are certainly important to the film’s being, of course, but its real heart and soul lies in its middle section: that lengthy passage set at the edge of civilization, in the south of France, as Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo)—now liberated from the alienating clutches of his privileged life—strives to live out his dream of intellectual freedom, while the less introspectively inclined Marianne (Anna Karina) yearns to “go back to our detective novel, with fast cars and guns and nightclubs.” This passage is perhaps the most personal and resonant in Pierrot le fou: no longer shackled by the chains of narrative and genre expectations (which of course Godard tries to undermine in his usual postmodern way), Godard himself, ever the intellectually searching mind, is free to give full rein to all the philosophical and political inquiries that are weighing on him.

What exactly is on his mind, then?

Pierrot le fou, of course, abounds in a wide variety of artistic references (Premiere.com critic Glenn Kenny recently compiled an ambitious three-part bibliography explaining Godard’s literary references here, here and here), but one work that he doesn’t reference explicitly is Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy, in which the controversial 19th-century German philosopher famously suggested that art—Greek tragedy and music, specifically—was, at its height, an intertwining of Apollo and Dionysus: the former signifying “plastic” truth, the latter representing intoxication and madness. Thus, great art, Nietzsche believed, was a juncture between those two poles—the Apollonian supported by the Dionysian, or (to risk oversimplifying Nietzsche’s argument) intellectual awareness propped up by emotion and feeling. We buy into the artistic illusion because the Dionysian elements rope us into accepting and becoming lost in it.

Pierrot le fou, of course, abounds in a wide variety of artistic references (Premiere.com critic Glenn Kenny recently compiled an ambitious three-part bibliography explaining Godard’s literary references here, here and here), but one work that he doesn’t reference explicitly is Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy, in which the controversial 19th-century German philosopher famously suggested that art—Greek tragedy and music, specifically—was, at its height, an intertwining of Apollo and Dionysus: the former signifying “plastic” truth, the latter representing intoxication and madness. Thus, great art, Nietzsche believed, was a juncture between those two poles—the Apollonian supported by the Dionysian, or (to risk oversimplifying Nietzsche’s argument) intellectual awareness propped up by emotion and feeling. We buy into the artistic illusion because the Dionysian elements rope us into accepting and becoming lost in it.In Nietzsche’s own words (from the Francis Golffing translation):

“At the point that matters most the Apollonian illusion has been broken through and destroyed. This drama which deploys before us, having all its movements and characters illumined from within by the aid of music—as though we witnessed the coming and going of the shuttle as it weaves the tissue—this drama achieves a total effect quite beyond the scope of any Apollonian artifice. In the final effect of tragedy the Dionysiac element triumphs once again: its closing sounds are such as were never heard in the Apollonian realm. The Apollonian illusion reveals its identity as the veil thrown over the Dionysiac meanings for the duration of the play, and yet the illusion is so potent that at its close the Apollonian drama is projected into a sphere where it begins to speak with Dionysiac wisdom, thereby denying itself and its Apollonian concreteness. The difficult relations between the two elements in tragedy may be symbolized by a fraternal union between the two deities: Dionysus speaks the language of Apollo, but Apollo, finally, the language of Dionysus; thereby the highest goal of tragedy and of art in general is reached.”

As far as I know, Godard hasn’t been connected much with Nietzsche, and for good reason. Even when his films—specifically his early-’60s works—still relied somewhat on story and character, Godard was rarely interested in maintaining any kind of façade: he was more often than not tearing down the fourth wall, reminding us of the precariousness of the cinematic artifice, and analyzing the mechanisms underneath (fiddling around with the soundtrack, jolting us from classical Hollywood complacency with “shocking” jump cuts, etc).

As far as I know, Godard hasn’t been connected much with Nietzsche, and for good reason. Even when his films—specifically his early-’60s works—still relied somewhat on story and character, Godard was rarely interested in maintaining any kind of façade: he was more often than not tearing down the fourth wall, reminding us of the precariousness of the cinematic artifice, and analyzing the mechanisms underneath (fiddling around with the soundtrack, jolting us from classical Hollywood complacency with “shocking” jump cuts, etc).Because of this, many have tagged him as a Brechtian, carrying on elements of the German playwright’s “epic theatre” tradition, which, through alienation techniques, attempted to bring the spectator closer to a drama’s content without the distraction of emotional involvement—in a way, zapping the Dionysian right out of art. And yet much of Godard’s early-’60s films, true to Nietzschean form, balance intellectual provocation with feeling and vitality. Witness, for instance, the depth of feeling bridging the emotional distance of Contempt, the effervescence underlying the musical-comedy genre analysis of A Woman is a Woman, or the fondness for his low-down characters in Band of Outsiders.

Pierrot le fou, however, represented a turning point in Godard’s artistic development. Looking at it in the context of the films that came before and after it, one can view it as a synthesis work, one that summarizes his thematic and sensual fascinations while anticipating the more distinctly Brechtian cinematic essays that would populate his late-’60s output, when characters didn’t matter so much to him as political ideas and detached examination of youth, French society, the world around us. The Hollywood genres he loved so much could no longer contain his intellectual enthusiasms, and Pierrot le fou burst the boundaries completely—filled to the gills with B-movie thriller conventions, quicksilver changes in tone and style, social satire, pointed political commentary, and eye-popping primary colors—in an attempt to reinvigorate his own energy for filmmaking and point the way toward future, more radical artistic directions.

But Pierrot le fou isn’t just a sensual celebration of one movie-obsessed director giving free rein to all of his impulses. Ever the questioning and engaged cinephile, Godard applies a distanced contemplation of that aforementioned Nietzschean artistic dichotomy of intellect and emotion, of Apollo and Dionysus. This clash between two human extremes of feeling goes all the way down to its form and style: there is a method to his surface madness. On a stylistic level, he accomplishes this as he has almost always done: he takes an interested but cool attitude toward his characters while indulging in his own passions for Pop Art imagery; film, literary and artistic references; and dexterous genre and formal play—with the effect that all those Hollywood-inspired genre elements are defamiliarized, put in quotation marks, made self-aware.

But Pierrot le fou isn’t just a sensual celebration of one movie-obsessed director giving free rein to all of his impulses. Ever the questioning and engaged cinephile, Godard applies a distanced contemplation of that aforementioned Nietzschean artistic dichotomy of intellect and emotion, of Apollo and Dionysus. This clash between two human extremes of feeling goes all the way down to its form and style: there is a method to his surface madness. On a stylistic level, he accomplishes this as he has almost always done: he takes an interested but cool attitude toward his characters while indulging in his own passions for Pop Art imagery; film, literary and artistic references; and dexterous genre and formal play—with the effect that all those Hollywood-inspired genre elements are defamiliarized, put in quotation marks, made self-aware.Right at the center of Pierrot le fou, however, are the two characters, Ferdinand and Marianne, representing the two sides of the Nietzschean coin. They both escape from the endless drone of bourgeois existence, epitomized by a party scene in which most of the partygoers speak in the language of magazine ads (“To combat underarm perspiration,” says one woman without a trace of irony, “I use Printil after my bath for all-day protection”). However, once they drive their car into the Mediterranean Sea and Ferdinand decides to start a new life—one in which he can read, write, and concentrate on his own artistic development—a rift between the two develops. For Ferdinand, this kind of Jules Verne-like existence represents the height of freedom; for Marianne, his secluded-artist lifestyle is just as stifling as her previous life back in Paris. Marianne is the one who acts on her emotional impulses: she breaks out into song and dance at two memorably random moments; she instigates the rekindling of their love affair (when she passionately says “I’m putting my hand on your knee,” Ferdinand disinterestedly responds “Me too, Marianne”); she’s the one who would rather listen to the latest pop single instead of reading (“Music after literature,” Ferdinand implores). She’s all sensual pleasure, while he’s all hardcore intellectualism—she’s Dionysus, he’s Apollo.

The scene that best summarizes this contradiction begins with Marianne walking along the Mediterranean shore, frustratingly crying out “What am I to do? I don’t know what to do!” Ferdinand, of course, is reading while soaking in the sun (with a parrot on his lap). When he asks Marianne why she looks so sad, she responds, “Because you speak to me in words, and I look at you in feelings.” When they both try to have a real conversation, they name things that immediately come to their mind. Marianne comes up with “flowers… animals… the blue of the sky… music… I don’t know, everything.” Ferdinand responds with, “ambition… hope… the way things move… accidents… What else? Well, everything.” Note that: everything. They’re both thinking about the world, it seems, but through totally antithetical perspectives—one attuned to the sensual beauties of the world, the other approaching it from an abstracted, dispassionate distance.