By Dan Jardine & Ben Livant Dan opens with a thematic overview:

Dan opens with a thematic overview:

Your reaction to Rashômon will likely be determined, at least in part, by your attitude towards Nietzsche’s assertion: "God is dead". Now, if you find that possibility liberating, you could be intrigued by the puzzles of perception presented by Rashômon. However, if this pronouncement angers you because it defies your faith in absolute truth, you will probably find Rashômon to be an existential experiment that serves no purpose—a sort of cinematic self-indulgence that makes a virtue of its own doubt.

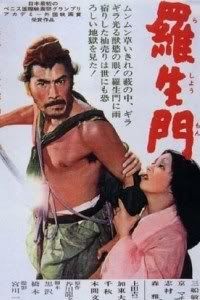

In Rashômon, a thief apparently rapes a young woman and murders her husband. A fourth person is apparently a witness. But to what? As we listen to the testimony of all involved (the dead man speaks though a medium) it becomes increasingly impossible to answer this question with any certainty. We have to wade through the contradictions, omissions and confusion to try to determine the truth, a feat made more difficult by the fact that none of the participants is particularly trustworthy. By the end of the movie, our emotions have been rubbed raw because we have been unable to empathize with a particular version of events. We finish in a moral quandary for we are no closer to determining the 'objective' truth than we were at the start of the film.

Thematically, Rashômon is a challenging philosophical exercise. Technically, the film is a tour de force of editing discipline and dramatic construction. The actors must recreate the same scene four times, playing their characters in completely different ways. Each re-telling has its own tone, and distinct point-of-view. Director Akira Kurosawa does a brilliant job of manipulating the mood, while each of the main actors is excellent. Toshirô Mifune (Kurosawa’s long-time leading man) as the thief and Machiko Kyô as the rape victim are particularly riveting. While the style of the performances may seem occasionally strained or overly technical to unfamiliar western eyes, these portraits are fascinating and our recognition of their artifice adds to our suspicion that the truth is not being told. Or maybe it is. It remains unclear how to know. Kurosawa has some bad news for you X-Philes out there: perhaps the truth is NOT out there. And maybe it isn't in here either.

Then Ben: What are you going to do? Sometimes the critics are right. Sometimes the director and cinematographer remember correctly as well. Fifty-eight years later all that's left for me to do is confirm that it continues to stand the test of time, job one for great art. The film, plus the Special Feature interviews, plus the little booklet with the original two stories, the excerpt of Kurosawa's autobiography and the historical discussion by Stephen Prince—the whole Criterion package was an exceptionally educational experience.

What are you going to do? Sometimes the critics are right. Sometimes the director and cinematographer remember correctly as well. Fifty-eight years later all that's left for me to do is confirm that it continues to stand the test of time, job one for great art. The film, plus the Special Feature interviews, plus the little booklet with the original two stories, the excerpt of Kurosawa's autobiography and the historical discussion by Stephen Prince—the whole Criterion package was an exceptionally educational experience.

Robert Altman I found especially on the money, his awareness of being a foreigner to all sorts of cultural codes readily comprehensible to the Japanese and, even more, his treatment of the "seeing is believing" cognitive rule of thumb. What his treatment implicitly explained is that, as an investigation into the subjectivity of truth, this particular investigation could only have been conducted in the medium of film. An approximation might be conducted as live theater, but this could never be as powerful because nothing can fool the eye like the camera and it is precisely this fooling of the eye which constitutes the technical basis for the philosophic problematic.

And this gives me a chance to beat on one of my favorite drums. For Kurosawa, the "tricks" of technique, the "play" in form, the matters of style are not considered the stuff of content, the substance of the film. Quite the contrary, they serve the epistemological ambiguity and moral anguish being communicated. In his essay on the film, Prince comments, "Style for Kurosawa is not an empty flourish." Damn straight. Hence, Rashômon—much much more indirectly and ultimately with far greater artistic power—delivers the moral mandate for film-making itself that is front and center in Kieslowski's compelling Camera Buff. If you are going to "fool the eye" you better be doing it to say something worth saying.

One of the things given only cursory mention by Prince that I couldn't stop remembering was that this film was released only half a decade after the atomic bombings. That Kurosawa could not go over to total despair, that he had to provide an act of redemption to the woodcutter in the final scene, this says a lot about his personal emotional healthiness. After all, nothing of the sort happens in either of the two original stories. Or is it just the 1950's Japanese version of the Hollywood happy ending for commercial considerations? I think not. I won't go on and on. But I do want to give myself credit for noticing the technical brilliance of the woodcutter's initial walk into the forest. While watching it, I didn't understand it. I didn't know yet that to enter the forest was to fall into intellectual confusion. This crisis of reason is a specifically rationalist take on the standard metaphor we all know from the Brothers Grimm: i.e., the forest as the ‘other’ of civilization. I grasped this well enough later on, but during the scene, it seemed so long and pointless. This lapse in my interpretive ability created a space in my technical sensitivity. I began to wonder how in hell they filmed the scene. It was amazing. So I was fascinated by the behind-the-scenes explanation that was provided. Brilliant! It's just stupid how good it is. The whole film. You know the feeling you sometimes get that it is somehow rude that a craftsman crafted something so... perfectly. The guy was definitely visited by The Muse.

I won't go on and on. But I do want to give myself credit for noticing the technical brilliance of the woodcutter's initial walk into the forest. While watching it, I didn't understand it. I didn't know yet that to enter the forest was to fall into intellectual confusion. This crisis of reason is a specifically rationalist take on the standard metaphor we all know from the Brothers Grimm: i.e., the forest as the ‘other’ of civilization. I grasped this well enough later on, but during the scene, it seemed so long and pointless. This lapse in my interpretive ability created a space in my technical sensitivity. I began to wonder how in hell they filmed the scene. It was amazing. So I was fascinated by the behind-the-scenes explanation that was provided. Brilliant! It's just stupid how good it is. The whole film. You know the feeling you sometimes get that it is somehow rude that a craftsman crafted something so... perfectly. The guy was definitely visited by The Muse.

And Dan:

The element of the exotic is always an interesting one with Kurosawa, because he got in such hot water with his native land for being so in love with the cinema and techniques of the west. Yet, to you and I (and, I suspect, most filmgoers who first came across his work in the 40s and 50s) a film like Rashômon seems like it comes to us from another world. Imagine how exotic he would have seemed had he not been a big fan of John Ford! We westerners probably never would have heard of him.

Rashômon adheres because it is both alien and accessible. The story's setting might as well be a fairy tale for most of us in the west; the characters are so foreign to our experience. And the acting is so far from anything we are familiar and/or comfortable with, particularly the apparent screechy excess of the female victim, that it pushes our sense of other-ness to the seeming breaking point. BUT, this multi-foliate flower of a tale has much that we recognize as well. The character's flaws are as familiar to us as any in western literature from the time of Chaucer onward, and Kurosawa's many narratives remain clear and distinct despite their contradictions because he edits them together (and keeps them apart) so beautifully that it makes the journey through this confusion nearly effortless for the viewer.

BUT, this multi-foliate flower of a tale has much that we recognize as well. The character's flaws are as familiar to us as any in western literature from the time of Chaucer onward, and Kurosawa's many narratives remain clear and distinct despite their contradictions because he edits them together (and keeps them apart) so beautifully that it makes the journey through this confusion nearly effortless for the viewer.

So, yes, style contributes impressively to the thematic substance of the film, as the moral ambiguity and existential crisis that the narratives elicit from the characters and audience are captured in some striking imagery (the sunlight speckling through the woods being Kurosawa's money shot in that regard). I'm not as sure as you that the happy ending works; it feels kind of forced given the despair we've been witnessing throughout. Then again, at this point in its history, did Japan really need another knee to the gonads?

Then Ben:

I think your treatment is quite dialectical. You are explaining a dynamic interpenetration of opposites. What is more, we are getting beyond film criticism as such and jumping full bore into cultural studies because the issue really is one of the relation between an artistic work and a non-domestic audience reception of it. I didn't want to say a "foreign" audience because it seems to me that much of what you are explaining is the non-foreign reception of what is, dialectally, plainly alien stuff. To simply suggest that the artistic work is therefore "universal" is not incorrect but is analytically crude and ultimately empty. The dialectics you foster deal with the relation between concrete (Japanese) forms and universal (humanist) themes. I like this in and of itself, but I also like it as an all-purpose methodology; indeed, I am imposing this methodological paradigm of mine on your treatment. I won't bore you further with my personal intellectual religion. Suffice to finish by suggesting that this dialectic is at the heart of a good relation between form and content as distinct from a one-sided, bad relation. For style is always a concrete thing. Content may or may not be universal, but we deem it more worthwhile when it is, we judge the work superior when it is. So the whole problem of style and content is derivative of a deeper, more abstract matter concerning the dialectics of the concrete and the universal. Image/Sound/Extras: The stunning transfer in Rashômon is impressive given the importance of the film’s treatment of light and shadow in exploring the symbolism of truth and deceit. Kurosawa’s radical decision and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa’s ability to point the camera straight at the sun through an umbrella of foliage is rendered in a particularly impressive fashion. Speaking of Miyagawa, the Criterion disc also boats excerpts from an informative documentary on the work and life of this vital cinematographer who worked on 134 films with nearly all of Japan’s most important directors.

Image/Sound/Extras: The stunning transfer in Rashômon is impressive given the importance of the film’s treatment of light and shadow in exploring the symbolism of truth and deceit. Kurosawa’s radical decision and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa’s ability to point the camera straight at the sun through an umbrella of foliage is rendered in a particularly impressive fashion. Speaking of Miyagawa, the Criterion disc also boats excerpts from an informative documentary on the work and life of this vital cinematographer who worked on 134 films with nearly all of Japan’s most important directors.

Robert Altman’s brief but pithy introduction is likewise useful, as well as full of the master’s wry wit. The film is a poem, that challenges our beliefs that if we see it, it must be true ("seeing is believing" is inverted, as Kurosawa seems to be positing that "believing is seeing"). Anyone who loves Rashômon will have a hard time arguing with Altman’s proclamation that the film changed what is possible and what is desirable about film. The audio commentary by historian and film buff Donald Richie, a staple of Criterion’s releases, and one of the world’s foremost experts on Nipponese cinema, is similarly thoughtful and engaging.

Finally, the disc is accompanied by a handy booklet that boasts not only both source materials (Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s "In the Grove" and "Rashômon", but also two very handy essays, one by Kurosawa himself, and the other by noted film scholar Stephen Prince. Kurosawa’s work offers a fascinating and richly detailed first hand account of the crafting of Rashômon, while Prince’s academic study gives us very helpful lessons in both the film’s influences and its substantial influence. Prince reinforces the importance of acknowledging Kurosawa’s accomplishments in this film, both in its modernist narrative and the technical triumph that saw the great director bend the medium’s grammar to the uncertainty and confusion at the heart of the film’s existential agony.

____________________________________________________

Dan Jardine is a contributor to The House Next Door and the publisher of Cinemania.

Ben Livant is a jazz lover and good friend of Dan's who he has been lending movies to for a while now.

Thursday, February 1, 2007

The Criterion Collection #138: Rashômon

Labels:

Akira Kurosawa,

Ben Livant,

Dan Jardine,

Rashômon

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)