By Dan Callahan So, a “proletariat trilogy” from the eighties by a Finnish director? It doesn’t sound too delightful, does it? But the three Aki Kaurismäki films collected in this Criterion release from their Eclipse line are delightful, on some level. They all involve people who work at low-level jobs: garbage-men, factory workers of all kinds, shop girls. In the second film, Ariel (1988), the heroine (Susanna Haavisto) begins as a meter maid giving out tickets, then progresses to jobs where she always seems to be cutting up disgustingly large sides of beef. Yet these movies don’t feel like drudgery, maybe because they aren’t in any way realistic; they take place in a tightly controlled world of their own. I’ve never been to Finland, but I’d be surprised to find even a vestige of Kaurismäki’s grim, deadpan cuteness.

So, a “proletariat trilogy” from the eighties by a Finnish director? It doesn’t sound too delightful, does it? But the three Aki Kaurismäki films collected in this Criterion release from their Eclipse line are delightful, on some level. They all involve people who work at low-level jobs: garbage-men, factory workers of all kinds, shop girls. In the second film, Ariel (1988), the heroine (Susanna Haavisto) begins as a meter maid giving out tickets, then progresses to jobs where she always seems to be cutting up disgustingly large sides of beef. Yet these movies don’t feel like drudgery, maybe because they aren’t in any way realistic; they take place in a tightly controlled world of their own. I’ve never been to Finland, but I’d be surprised to find even a vestige of Kaurismäki’s grim, deadpan cuteness.

These three films are unusual in several ways. Notably, they all run around an hour and ten minutes, as if Kaurismäki knew that a little of his particular sensibility went a long way. They all use music inventively, either to provide emotion where there is none, or to act as counterpoint to the comically drab lives of the protagonists. The funniest thing about the first film, Shadows in Paradise (1986), is the title: Kaurismäki’s vision of the Finnish city Helsinki is about as far from paradise as you can get, and you can’t imagine anything in this city that could cause a shadow, either physically or psychically.

There never seems to be anybody on the pleasantly lonely streets of Shadows in Paradise, and there’s no street noise, either; as garbage men go to work in the film’s first shots, none of them says a word to each other. When one of the garbage men, Nikander (Matti Pellonpää) takes his girl Illona (Kati Outinen) to a restaurant, the maître d' tells them that it’s full (earlier in the film, Ilona asks for a hotel room, and has to wait quite a while to find out that it’s full, too). Kaurismäki’s comic timing is slightly off in these scenes, but Outinen lands a huge laugh when she defends Nikander to a girl she works with, then languidly runs down the guys this girl goes out with. Outinen gets the laugh by effecting an “I couldn’t care less, but why not keep going?” mood, and Kaurismäki is smart enough to keep the camera on her as she does this. The resolution of the slight story in Shadows in Paradise is fun, but it has a whiff of wish fulfillment, and this wish fulfillment takes over in Ariel, the weakest of the three films. It begins again with men going to work, this time in a mine, and it quickly sketches in another droll love story. There is a very funny series of scenes set in an eerily genteel flophouse, a place where men put up framed photos and silently read their papers, but Ariel flounders when it takes up a crime plot that concludes in an absurdly unconvincing prison escape. Kaurismäki’s distinctive brand of unreality can’t handle the mechanics of a standard story like this. A stay in prison isn’t at all different in Ariel from life on the outside, but this joke isn’t particularly pointed; what’s needed is a touch more outrage, a bit of wildness. As it is, the film just dribbles nicely along to a silly conclusion scored to a Finnish version of “Over the Rainbow.”

The resolution of the slight story in Shadows in Paradise is fun, but it has a whiff of wish fulfillment, and this wish fulfillment takes over in Ariel, the weakest of the three films. It begins again with men going to work, this time in a mine, and it quickly sketches in another droll love story. There is a very funny series of scenes set in an eerily genteel flophouse, a place where men put up framed photos and silently read their papers, but Ariel flounders when it takes up a crime plot that concludes in an absurdly unconvincing prison escape. Kaurismäki’s distinctive brand of unreality can’t handle the mechanics of a standard story like this. A stay in prison isn’t at all different in Ariel from life on the outside, but this joke isn’t particularly pointed; what’s needed is a touch more outrage, a bit of wildness. As it is, the film just dribbles nicely along to a silly conclusion scored to a Finnish version of “Over the Rainbow.”

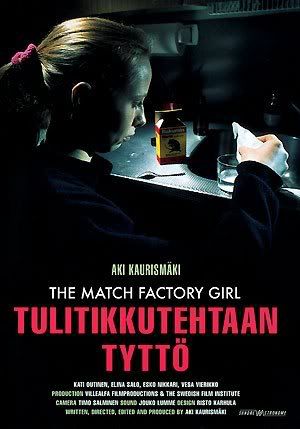

But the third film in the set, The Match Factory Girl (1990), is a small masterpiece where Kaurismäki hones a savage story to such a fine edge that it wouldn’t be embarrassing to compare it to the best of Bresson. At its center is Kati Outinen, who played the girlfriend in Shadows in Paradise. Here she plays Iris, a sullen girl who works in a factory and lives at home with her mother and stepfather. We see her cooking a homely meal for them; afterwards, Kaurismäki juxtaposes TV coverage of the massacre in Tiananmen Square with Iris making herself up to go out dancing. When he cuts to a kitschy, time-warp sort of dance hall, the contrast with the violence we’ve just seen on television is shocking, and funny, too; it signals that The Match Factory Girl is going to be in a much darker key than the first two films. Iris just sits by herself at the dance hall, sipping an orange drink. Finishing it, she puts it down next to a row of empty bottles, which lets us know that she’s been consuming the same orange drink in one spot for a very long time. It’s the kind of pitiful detail that makes you want to laugh at Iris, but the laugh catches in your throat. Poor, glowering Iris meets a man (Vesa Vierikko) at another dance hall, and she actually dances with him; the morning after, he puts some money on her dresser and leaves, another moment where you don’t know whether to laugh or cringe. There’s almost no dialogue in The Match Factory Girl, and when there is, it’s usually a man telling Iris something awful, or insulting, or both. Increasingly hopeless, Iris sits in a movie theater with tears running down her face; gradually, we hear the soundtrack and realize that she’s at a Marx Brothers movie! Clearly, Iris is an inconsolable girl who is inching closer and closer to the edge, and it’s easy to get transfixed by her sour pout, her accusatory blue eyes and the pink scrunchie that holds her blond hair in a tragic ponytail. The last third of the movie, where Iris takes definitive action, is swift, merciless, hilarious and perfectly judged. Outinen does no “acting” whatsoever, yet this is a truly exceptional performance. In its abstract terms, The Match Factory Girl makes you understand why some people are driven to unconscionable deeds, and the whole movie is a triumph for Kaurismäki and his minimalist methods.

Poor, glowering Iris meets a man (Vesa Vierikko) at another dance hall, and she actually dances with him; the morning after, he puts some money on her dresser and leaves, another moment where you don’t know whether to laugh or cringe. There’s almost no dialogue in The Match Factory Girl, and when there is, it’s usually a man telling Iris something awful, or insulting, or both. Increasingly hopeless, Iris sits in a movie theater with tears running down her face; gradually, we hear the soundtrack and realize that she’s at a Marx Brothers movie! Clearly, Iris is an inconsolable girl who is inching closer and closer to the edge, and it’s easy to get transfixed by her sour pout, her accusatory blue eyes and the pink scrunchie that holds her blond hair in a tragic ponytail. The last third of the movie, where Iris takes definitive action, is swift, merciless, hilarious and perfectly judged. Outinen does no “acting” whatsoever, yet this is a truly exceptional performance. In its abstract terms, The Match Factory Girl makes you understand why some people are driven to unconscionable deeds, and the whole movie is a triumph for Kaurismäki and his minimalist methods.

_________________________________________________

House contributor Dan Callahan's writing has appeared in Slant Magazine, Bright Lights Film Journal and Senses of Cinema, among other publications.

Friday, December 1, 2006

Eclipse Series 12: Aki Kaurismäki’s Proletariat Trilogy

Eclipse Series 10: Silent Ozu—Three Family Comedies

By Dan Callahan Most dedicated film lovers are familiar with the elegiac '50s family dramas of Yasujiro Ozu, classics like Late Spring (1949) and Tokyo Story (1953). Much as they are cherished and respected, even his most fervent admirers have admitted the sameness of these films, in which a constantly smiling Setsuko Hara beams from her tatami mat and says, “Life is certainly disappointing!” After her pronouncement, Ozu cuts to a boat chugging along a river; he then cuts back to Hara, who has a measured shot/reverse shot conversation with one of her parents. Mom or Dad smiles finally, then reflects, “My dreams of youth are gone!” Then Ozu cuts to laundry flapping in the breeze against a mackerel sky, etc. To paraphrase Virginia Woolf, Ozu prefers to suffer and understand rather than to fight and enjoy. His Zen resignation is like a drug to some, but it must be said that Ozu’s basic attitude can seem complacent, even maddening, especially to American viewers whose birthright has always been the urge to tell someone off, make a change, start again. Of course, this “anything is possible” point of view has led to a lot of pain for most of our ambitious American strivers, so a pinch or more of Ozu’s philosophy can be beneficial to us.

Most dedicated film lovers are familiar with the elegiac '50s family dramas of Yasujiro Ozu, classics like Late Spring (1949) and Tokyo Story (1953). Much as they are cherished and respected, even his most fervent admirers have admitted the sameness of these films, in which a constantly smiling Setsuko Hara beams from her tatami mat and says, “Life is certainly disappointing!” After her pronouncement, Ozu cuts to a boat chugging along a river; he then cuts back to Hara, who has a measured shot/reverse shot conversation with one of her parents. Mom or Dad smiles finally, then reflects, “My dreams of youth are gone!” Then Ozu cuts to laundry flapping in the breeze against a mackerel sky, etc. To paraphrase Virginia Woolf, Ozu prefers to suffer and understand rather than to fight and enjoy. His Zen resignation is like a drug to some, but it must be said that Ozu’s basic attitude can seem complacent, even maddening, especially to American viewers whose birthright has always been the urge to tell someone off, make a change, start again. Of course, this “anything is possible” point of view has led to a lot of pain for most of our ambitious American strivers, so a pinch or more of Ozu’s philosophy can be beneficial to us. Ozu made a lot of films in the '30s, many of which are silent, some of which are lost, and these early films are seldom screened, so the new Eclipse series release, "Silent Ozu—Three Family Comedies", is valuable in that it lets us see the genesis of his refined late style. The initial movie in the set, Tokyo Chorus (1931) has been identified by some writers as Ozu’s first really mature work, and it does have a cohesiveness that some of his other '30s films lack. Chorus opens with a bunch of schoolboys being drilled in marching formation; one of the boys is rebellious, sticking his tongue out at the headmaster and making a face at him. This boy is also dreamy and contemplative: we see him sitting and staring at trees shivering in the wind, an image that haunts the rest of the movie. Then there’s a jump ahead in time, and the boy (Tokihiko Okada) is now an office drone with a wife and two small children. Okada’s daughter is played by a seven-year old Hideko Takamine, who grew up into a major actress for Mikio Naruse and other Japanese directors in the fifties. Takamine is instantly recognizable here; it’s startling to see her famously pinched, wary face on top of a little girl body. And she’s already a nag: “Daddy’s a liar!” baby Takamine whines, at one point.

Ozu made a lot of films in the '30s, many of which are silent, some of which are lost, and these early films are seldom screened, so the new Eclipse series release, "Silent Ozu—Three Family Comedies", is valuable in that it lets us see the genesis of his refined late style. The initial movie in the set, Tokyo Chorus (1931) has been identified by some writers as Ozu’s first really mature work, and it does have a cohesiveness that some of his other '30s films lack. Chorus opens with a bunch of schoolboys being drilled in marching formation; one of the boys is rebellious, sticking his tongue out at the headmaster and making a face at him. This boy is also dreamy and contemplative: we see him sitting and staring at trees shivering in the wind, an image that haunts the rest of the movie. Then there’s a jump ahead in time, and the boy (Tokihiko Okada) is now an office drone with a wife and two small children. Okada’s daughter is played by a seven-year old Hideko Takamine, who grew up into a major actress for Mikio Naruse and other Japanese directors in the fifties. Takamine is instantly recognizable here; it’s startling to see her famously pinched, wary face on top of a little girl body. And she’s already a nag: “Daddy’s a liar!” baby Takamine whines, at one point.

There’s an earthy, even scatological humor in Tokyo Chorus that Ozu would gradually pare away from his films, by and large, but his sense of resignation was present from the beginning. As Okada sits in a park, at loose ends and out of a job, a friend tells him that a bear has escaped from a nearby zoo. Okada smiles at his excited pal and says, “A bear getting out isn’t going to change our lives.” This “what will be will be” vibe is fine for some situations, but Ozu always takes it too far. After all, the bear might be right behind Okada and ready to eat him; the least he could do would be to get up and leave the area, but no, it doesn’t matter, he says, for nothing matters to him at this moment. At its worst, Ozu’s seemingly serene acceptance of life is actually close to do-nothing, harmful nihilism. Still, it’s hard to argue with the long scene where the desolate family tries to forget their problems with an extended game of patty cake; we can actually see Ozu’s anxious cheerfulness visibly burning away his characters’ worries. In the end, though, Ozu asks us to weep for his hero, forced to take a demeaning job with his old schoolmaster. Naruse also knew that his people had to make sacrifices to go on, but I’ll take the grown-up Takamine’s wry, almost humorous confrontation with her hated job at the end of When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960) over Ozu’s more adolescent and not at all funny look at defeat in Tokyo Chorus. I Was Born, But... (1932) is Ozu’s best-known early film, and it fully deserves its reputation. We watch two young boys doing ordinary things like cutting school and playing with other kids for a while before the real subject of the movie rears its ugly head. About an hour in, the boys sit and watch their wage slave father, Yoshii (Tatsuo Saito), make the same dumb faces and gestures over and over again, in movies that are being projected for some of his co-workers. Watching the co-workers’ reactions, Yoshii’s sons understand instinctively that their father is a figure of fun to the other adults. To a kid, especially a boy, there’s nothing worse than a realization like that, and their violent reaction at home later on is both grueling and fair. “You tell us to become somebody, but you’re nobody!” one of them shouts at Yoshii. Their father doesn’t defend himself, and their mother is an even weaker presence. “I give up,” says Yoshii, grabbing a bottle of liquor, as many Ozu men will do in later films. This scene of fatherly self-deprecation is unthinkable in an American movie, and it says a lot about Ozu’s essential despair, just as the final, small act of kindness on the part of one of the boys’ friends, which ends the film, says a lot about his appreciation of life’s small mercies.

I Was Born, But... (1932) is Ozu’s best-known early film, and it fully deserves its reputation. We watch two young boys doing ordinary things like cutting school and playing with other kids for a while before the real subject of the movie rears its ugly head. About an hour in, the boys sit and watch their wage slave father, Yoshii (Tatsuo Saito), make the same dumb faces and gestures over and over again, in movies that are being projected for some of his co-workers. Watching the co-workers’ reactions, Yoshii’s sons understand instinctively that their father is a figure of fun to the other adults. To a kid, especially a boy, there’s nothing worse than a realization like that, and their violent reaction at home later on is both grueling and fair. “You tell us to become somebody, but you’re nobody!” one of them shouts at Yoshii. Their father doesn’t defend himself, and their mother is an even weaker presence. “I give up,” says Yoshii, grabbing a bottle of liquor, as many Ozu men will do in later films. This scene of fatherly self-deprecation is unthinkable in an American movie, and it says a lot about Ozu’s essential despair, just as the final, small act of kindness on the part of one of the boys’ friends, which ends the film, says a lot about his appreciation of life’s small mercies. The third film in the set, Passing Fancy (1933), is nowhere near as good as the first two movies. It really wants to be a talkie; there are too many titles for all the conversation scenes, and the setpiece sequence, a confrontation between a boy and his drunken, good-for-nothing father, suffers in comparison with the tougher, similar scene in I Was Born, But...; what was true and moving in that film seems maudlin here. Passing Fancy ends with the contemplation of some trees, bringing us full circle back to the daydreaming image at the beginning of Tokyo Chorus. This was a director who stressed such continuity: Ozu’s technical skills are already impressive in these three early films, and his way of looking at life and people is as firm at age thirty as it would be at age fifty. Let us enjoy and even learn from Ozu, but let’s not accept all of his ideas about human forbearance without a dash or two of our own American “get up and go,” seasoned heavily with Naruse’s hardboiled black humor.

The third film in the set, Passing Fancy (1933), is nowhere near as good as the first two movies. It really wants to be a talkie; there are too many titles for all the conversation scenes, and the setpiece sequence, a confrontation between a boy and his drunken, good-for-nothing father, suffers in comparison with the tougher, similar scene in I Was Born, But...; what was true and moving in that film seems maudlin here. Passing Fancy ends with the contemplation of some trees, bringing us full circle back to the daydreaming image at the beginning of Tokyo Chorus. This was a director who stressed such continuity: Ozu’s technical skills are already impressive in these three early films, and his way of looking at life and people is as firm at age thirty as it would be at age fifty. Let us enjoy and even learn from Ozu, but let’s not accept all of his ideas about human forbearance without a dash or two of our own American “get up and go,” seasoned heavily with Naruse’s hardboiled black humor.

Image/Sound/Extras: Tokyo Chorus is the most visually innovative of the films, so it’s unfortunate that the image is so badly damaged; the entire movie is fighting against a veil of print decay. Donald Sosin’s piano score for Chorus is upbeat and sprightly even when things look bleakest for the characters, which works well at first, but begins to seem strange as the film goes on. I Was Born, But… and Passing Fancy look fine, and Sosin’s scores for both are excellent. No extras, since this is an Eclipse no-frills release.

_________________________________________________

House contributor Dan Callahan's writing has appeared in Slant Magazine, Bright Lights Film Journal and Senses of Cinema, among other publications.

Eclipse Series 8: Lubitsch Musicals

By Dan Callahan The four Ernst Lubitsch musicals collected in this box set mark a transitional period in his work, a bridge from perfectly judged silent films like So This is Paris (1926) to the risky, spare achievements of later movies like To Be or Not to Be (1942) and Cluny Brown (1946). Maurice Chevalier and Jeannette MacDonald are the nominal stars of this early talkie series, either together or paired with other players, and you just have to accept and even embrace the former's full-frontal “ooh la la!” chortles and the latter's not-yet-calcified operetta hauteur if you plan to make it through these pictures alive. They both came from the stage, and they have just the right lightly formal quality for Lubitsch’s theatrical bits of business. Though a little of Chevalier’s strenuous Gallic charmboat act goes a long, long way, it must be said that Lubitsch makes MacDonald surprisingly sexy and even touching in her pre-Nelson Eddy salad days at Paramount.

The four Ernst Lubitsch musicals collected in this box set mark a transitional period in his work, a bridge from perfectly judged silent films like So This is Paris (1926) to the risky, spare achievements of later movies like To Be or Not to Be (1942) and Cluny Brown (1946). Maurice Chevalier and Jeannette MacDonald are the nominal stars of this early talkie series, either together or paired with other players, and you just have to accept and even embrace the former's full-frontal “ooh la la!” chortles and the latter's not-yet-calcified operetta hauteur if you plan to make it through these pictures alive. They both came from the stage, and they have just the right lightly formal quality for Lubitsch’s theatrical bits of business. Though a little of Chevalier’s strenuous Gallic charmboat act goes a long, long way, it must be said that Lubitsch makes MacDonald surprisingly sexy and even touching in her pre-Nelson Eddy salad days at Paramount. The Love Parade (1929) opens with lots of quick cutting to close-ups of garters and tiny derringers and closing doors, as if Lubitsch is trying to continue the fluidity of his silent films in this early talkie context, much as Hitchcock clung to his montage effects in his first talkie, Blackmail (1929). Then Chevalier starts to sing to the camera, and it’s hard not to recoil from his “oh ho ho’s!” and cartoonish boasting about women, which never appear to have any firm basis in sexual reality. We then see MacDonald rise from her bed in fetching lingerie to long in song for a “Dream Lover.” She’s queen of a country called Sylvania, and gets a kick out of showing off her legs to her dirty old men cabinet ministers until she meets up with supposed lothario Chevalier. Lubitsch sends up the audience’s voyeurism by having all the film’s servants staring at the movie star couple through keyholes and open windows, vicariously thrilling to their anticipatory erotic excitement. The main theme here is the melancholy but also momentous promise of sex; all Lubitsch’s characters have one foot in bed at all times.

The Love Parade (1929) opens with lots of quick cutting to close-ups of garters and tiny derringers and closing doors, as if Lubitsch is trying to continue the fluidity of his silent films in this early talkie context, much as Hitchcock clung to his montage effects in his first talkie, Blackmail (1929). Then Chevalier starts to sing to the camera, and it’s hard not to recoil from his “oh ho ho’s!” and cartoonish boasting about women, which never appear to have any firm basis in sexual reality. We then see MacDonald rise from her bed in fetching lingerie to long in song for a “Dream Lover.” She’s queen of a country called Sylvania, and gets a kick out of showing off her legs to her dirty old men cabinet ministers until she meets up with supposed lothario Chevalier. Lubitsch sends up the audience’s voyeurism by having all the film’s servants staring at the movie star couple through keyholes and open windows, vicariously thrilling to their anticipatory erotic excitement. The main theme here is the melancholy but also momentous promise of sex; all Lubitsch’s characters have one foot in bed at all times. In The Love Parade’s scintillating first hour, Lubitsch insists that two people should have sex right away, and that there will be plenty more mysteries to unravel in subsequent couplings. The title song suggests that every woman Chevalier could ever bed is in MacDonald, somewhere, if he just looks at her closely enough over a long period of time. But the fact that she’s a queen proves intimidating. After their marriage, Chevalier is alarmed when he hears a royal cannon firing over and over again; it’s as if he’s afraid he can’t compete sexually with such heavy artillery. This is classic Lubitsch, a romantic dirty joke, but after the wedding night, The Love Parade sags, and the plot requires Chevalier to put queen MacDonald in her place, which gets depressing after a while. Lupino Lane and future tell-all alcoholic Lillian Roth pick up some slack with their acrobatic comic servant routines, but the film is far too long at 109 minutes. At the time, The Love Parade was a big hit, and you can still feel how fresh and inventive it must have felt in that arid, “microphone in the flowerpot” early talkie year.

In The Love Parade’s scintillating first hour, Lubitsch insists that two people should have sex right away, and that there will be plenty more mysteries to unravel in subsequent couplings. The title song suggests that every woman Chevalier could ever bed is in MacDonald, somewhere, if he just looks at her closely enough over a long period of time. But the fact that she’s a queen proves intimidating. After their marriage, Chevalier is alarmed when he hears a royal cannon firing over and over again; it’s as if he’s afraid he can’t compete sexually with such heavy artillery. This is classic Lubitsch, a romantic dirty joke, but after the wedding night, The Love Parade sags, and the plot requires Chevalier to put queen MacDonald in her place, which gets depressing after a while. Lupino Lane and future tell-all alcoholic Lillian Roth pick up some slack with their acrobatic comic servant routines, but the film is far too long at 109 minutes. At the time, The Love Parade was a big hit, and you can still feel how fresh and inventive it must have felt in that arid, “microphone in the flowerpot” early talkie year. Lubitsch’s follow-up, Monte Carlo (1930) is the weakest film in the set; even the most famous sequence, when MacDonald sings, “Beyond the Blue Horizon” on a train, is disappointingly truncated and reserved. Lubitsch never goes all-out with this very funny song of liberation; he simply holds a few medium shots of MacDonald singing in profile, then cuts to far-off peasants tentatively joining her as a chorus. The real problem here, though, is the leading man, Jack Buchanan, a big star of the London stage who is so hand-flappingly effeminate on screen that Lubitsch must have felt he had to fill the rest of the cast with even nellier men to make his star look manlier. This attempt at contrast proves disastrous, especially in a number called “Trimmin’ the Women,” where Buchanan and two campy little fellows (Tyler Brooke and John Roche) sing about how they love to get close to women’s hair: they practically fly around the room. MacDonald has to carry the love story all by herself, and the drawn-out plot quickly becomes tedious.

Lubitsch’s follow-up, Monte Carlo (1930) is the weakest film in the set; even the most famous sequence, when MacDonald sings, “Beyond the Blue Horizon” on a train, is disappointingly truncated and reserved. Lubitsch never goes all-out with this very funny song of liberation; he simply holds a few medium shots of MacDonald singing in profile, then cuts to far-off peasants tentatively joining her as a chorus. The real problem here, though, is the leading man, Jack Buchanan, a big star of the London stage who is so hand-flappingly effeminate on screen that Lubitsch must have felt he had to fill the rest of the cast with even nellier men to make his star look manlier. This attempt at contrast proves disastrous, especially in a number called “Trimmin’ the Women,” where Buchanan and two campy little fellows (Tyler Brooke and John Roche) sing about how they love to get close to women’s hair: they practically fly around the room. MacDonald has to carry the love story all by herself, and the drawn-out plot quickly becomes tedious. The Smiling Lieutenant (1931) represents a substantial leap forward, with Chevalier set off by two exciting Paramount women, Claudette Colbert and Miriam Hopkins. It’s Lubitsch pleasure without much Lubitsch depth, but diverting all the same. When Chevalier meets violinist Colbert, he tells her he plays the piano, and she suggests, “Sometime we might have a duet.” He leers at her and cries, “I love chamber music!” They’re obviously talking about sex, but Lubitsch toys with our expectations by then cutting to them actually playing music, as if he’s saying, “What did you think they were talking about? Get your mind out of the gutter!” They’re soon singing with each other over breakfast, with Chevalier claiming, “You put magic in the muffins!” while Colbert wrinkles her nose (it’s worth noting that her orchestra is called “The Viennese Swallows”!) Hopkins gives an expertly timed comic performance as plain-Jane royalty with Princess Leia buns on her ears who makes a play for Chevalier; Colbert gallantly helps her out by singing the unforgettable ditty, “Jazz Up Your Lingerie.” The fun evaporates, though, when Colbert tells her, “Girls who start with breakfast don’t usually stay for supper,” an unhappy bit of moralizing that goes against the message of The Love Parade.

The Smiling Lieutenant (1931) represents a substantial leap forward, with Chevalier set off by two exciting Paramount women, Claudette Colbert and Miriam Hopkins. It’s Lubitsch pleasure without much Lubitsch depth, but diverting all the same. When Chevalier meets violinist Colbert, he tells her he plays the piano, and she suggests, “Sometime we might have a duet.” He leers at her and cries, “I love chamber music!” They’re obviously talking about sex, but Lubitsch toys with our expectations by then cutting to them actually playing music, as if he’s saying, “What did you think they were talking about? Get your mind out of the gutter!” They’re soon singing with each other over breakfast, with Chevalier claiming, “You put magic in the muffins!” while Colbert wrinkles her nose (it’s worth noting that her orchestra is called “The Viennese Swallows”!) Hopkins gives an expertly timed comic performance as plain-Jane royalty with Princess Leia buns on her ears who makes a play for Chevalier; Colbert gallantly helps her out by singing the unforgettable ditty, “Jazz Up Your Lingerie.” The fun evaporates, though, when Colbert tells her, “Girls who start with breakfast don’t usually stay for supper,” an unhappy bit of moralizing that goes against the message of The Love Parade. The best film is the last, One Hour with You (1932), a remake of Lubitsch’s silent The Marriage Circle (1924), which was prepared by the busy auteur, but mostly directed by George Cukor. When he saw that the film was going to be success, Lubitsch attempted to get Cukor’s name taken off the credits, but Cukor took him to court and wound up with assistant billing. Just how much was done by each director is still in question, but it has more shading and depth than Lubitsch’s previous talkies, and this could be because these gifted men were working in tandem. Cukor gives it a brisker pace and he takes care with performances, so that MacDonald especially brings an emotion and sexuality to her role that she seldom showed elsewhere. On the other hand, it does have the darkening boudoir aspect of Lubitsch’s next film, one of his best, Trouble in Paradise (1932). Whoever is responsible for it, One Hour with You is a delight, especially its ending, which suggests that a little infidelity will never hurt a solid, pleasurable marriage.

The best film is the last, One Hour with You (1932), a remake of Lubitsch’s silent The Marriage Circle (1924), which was prepared by the busy auteur, but mostly directed by George Cukor. When he saw that the film was going to be success, Lubitsch attempted to get Cukor’s name taken off the credits, but Cukor took him to court and wound up with assistant billing. Just how much was done by each director is still in question, but it has more shading and depth than Lubitsch’s previous talkies, and this could be because these gifted men were working in tandem. Cukor gives it a brisker pace and he takes care with performances, so that MacDonald especially brings an emotion and sexuality to her role that she seldom showed elsewhere. On the other hand, it does have the darkening boudoir aspect of Lubitsch’s next film, one of his best, Trouble in Paradise (1932). Whoever is responsible for it, One Hour with You is a delight, especially its ending, which suggests that a little infidelity will never hurt a solid, pleasurable marriage.

Image/Sound/Extras (editor's note: click here for more in-depth technical information on this set from DVDBeaver): The Smiling Lieutenant (aspect ratio 1.21:1, monaural) looks the best of the four, almost pristine, but poor Monte Carlo (aspect ratio 1.20:1, monaural) is in bad shape. It even goes soft and out of focus twice before MacDonald sings “Beyond the Blue Horizon,” and the nighttime scenes are barely visible. The Love Parade (aspect ratio 1.21:1, monaural) is spotty, but quite acceptable for a film of its vintage, and One Hour with You (aspect ratio 1.36:1, monaural) is grainy when it needs to shimmer. Nevertheless, this is a valuable set for a quartet of films that have always been difficult to see. Per the Eclipse series mission statement, there are no extra features.

_________________________________________________

House contributor Dan Callahan's writing has appeared in Slant Magazine, Bright Lights Film Journal and Senses of Cinema, among other publications.

Eclipse Series 5: The First Films of Samuel Fuller

By Keith Uhlich Tempting as it is to describe Samuel Fuller as the cinema’s brute poet, the three films included on The Criterion Collection’s fifth Eclipse series (“The First Films of Samuel Fuller”) encourage a more multifaceted reading. Whether working as reporter or soldier, Fuller always had his hand in the arts, and he might be the living epitome of that old John Ford/Liberty Valance saw: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” His autobiography, A Third Face, pushed several friends and colleagues to an enthusiastic epiphany (“Sam Fuller won World War II!”) that I’m sure the stogie-chomping stalwart would have basked in for a delirious moment or two. But guaranteed the seriousness of his experiences would have intruded on this hypothetical reverie; for all his gruff joie de vivre, there’s a concomitantly profound sense of sadness underlying each and every shot of Fuller’s cinema.

Tempting as it is to describe Samuel Fuller as the cinema’s brute poet, the three films included on The Criterion Collection’s fifth Eclipse series (“The First Films of Samuel Fuller”) encourage a more multifaceted reading. Whether working as reporter or soldier, Fuller always had his hand in the arts, and he might be the living epitome of that old John Ford/Liberty Valance saw: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” His autobiography, A Third Face, pushed several friends and colleagues to an enthusiastic epiphany (“Sam Fuller won World War II!”) that I’m sure the stogie-chomping stalwart would have basked in for a delirious moment or two. But guaranteed the seriousness of his experiences would have intruded on this hypothetical reverie; for all his gruff joie de vivre, there’s a concomitantly profound sense of sadness underlying each and every shot of Fuller’s cinema. As both reporter and soldier, he was no doubt trained to bear witness to the moment, and it is this, more than anything, that ensured his long-standing B-level status among the cinema cognoscenti. Fuller isn’t one for making artful, mock-definitive statements about the world we live in – when he gets polemical (as in the explicit racial commentary of The Steel Helmet, one of the films included in this set), his observations tend to be intentionally rough around the edges, treading bitter, defeatist misanthropy. As a liberator of the concentration camps, Fuller certainly saw his fair share of the evil that humans do, and the majority of his films suggest that such collective dis-ease is ongoing, never-ending. Contented happiness, if it comes, is either a deceptive load of bullshit or merely a momentary uplift of the soul, unique to the individual experiencing it (and how often this latter incidence occurs, for Fuller’s characters, at the point of dying).

As both reporter and soldier, he was no doubt trained to bear witness to the moment, and it is this, more than anything, that ensured his long-standing B-level status among the cinema cognoscenti. Fuller isn’t one for making artful, mock-definitive statements about the world we live in – when he gets polemical (as in the explicit racial commentary of The Steel Helmet, one of the films included in this set), his observations tend to be intentionally rough around the edges, treading bitter, defeatist misanthropy. As a liberator of the concentration camps, Fuller certainly saw his fair share of the evil that humans do, and the majority of his films suggest that such collective dis-ease is ongoing, never-ending. Contented happiness, if it comes, is either a deceptive load of bullshit or merely a momentary uplift of the soul, unique to the individual experiencing it (and how often this latter incidence occurs, for Fuller’s characters, at the point of dying). I Shot Jesse James (1949) provides one such example of this. Fuller’s debut feature is remarkable for its sophisticated and intuitive treatment of a famed tale of the Old West, viewing Robert Ford’s (John Ireland) cowardly assassination of his friend and fellow thief Jesse James (Reed Hadley) as a quintessentially gay love story. Of I Shot Jesse James’ producer, Robert L. Lippert, Fuller observed, “[he was] too uptight to even pronounce the word homosexual,” and Fuller most certainly used this instinctive fear (one not only limited to his business partner) to his advantage. It’s not so much the explicit nature of some of the film’s allusions (James asking Ford to wash his back; the assassination itself, shot in such a way as to evoke rape) as it is Ireland’s interiorized performance and Fuller’s matter-of-fact mise en scene (complete with ripped-from-the-headlines transitional montages) that solidifies I Shot Jesse James’ accomplishments.

I Shot Jesse James (1949) provides one such example of this. Fuller’s debut feature is remarkable for its sophisticated and intuitive treatment of a famed tale of the Old West, viewing Robert Ford’s (John Ireland) cowardly assassination of his friend and fellow thief Jesse James (Reed Hadley) as a quintessentially gay love story. Of I Shot Jesse James’ producer, Robert L. Lippert, Fuller observed, “[he was] too uptight to even pronounce the word homosexual,” and Fuller most certainly used this instinctive fear (one not only limited to his business partner) to his advantage. It’s not so much the explicit nature of some of the film’s allusions (James asking Ford to wash his back; the assassination itself, shot in such a way as to evoke rape) as it is Ireland’s interiorized performance and Fuller’s matter-of-fact mise en scene (complete with ripped-from-the-headlines transitional montages) that solidifies I Shot Jesse James’ accomplishments. It would be enough for some artists to challenge the status quo by aligning audience sympathies with a murderer, but Fuller goes deeper into his protagonist’s tortured psyche, uncovering a sublimated sense of love that only finds expression as climax to his death rattle. Otherwise, Robert Ford walks around like an empty shell of a man, shunned by the community at large; forced, by monetary need, to re-enact James’ murder onstage; rejected by his actress girlfriend Cynthy Waters (Barbara Britton), who seems less put off by the murder itself than by the implication of something untoward underlying Ford’s actions. Fitting that it is she who hears his dying confession (“I’m sorry for what I done to Jess. I loved him.”) and that Fuller sees fit to exit the film on this decidedly bitter moment out of time. Like a ground-in punctuation mark closing out a frenetically hand-written confession, it packs a wallop.

It would be enough for some artists to challenge the status quo by aligning audience sympathies with a murderer, but Fuller goes deeper into his protagonist’s tortured psyche, uncovering a sublimated sense of love that only finds expression as climax to his death rattle. Otherwise, Robert Ford walks around like an empty shell of a man, shunned by the community at large; forced, by monetary need, to re-enact James’ murder onstage; rejected by his actress girlfriend Cynthy Waters (Barbara Britton), who seems less put off by the murder itself than by the implication of something untoward underlying Ford’s actions. Fitting that it is she who hears his dying confession (“I’m sorry for what I done to Jess. I loved him.”) and that Fuller sees fit to exit the film on this decidedly bitter moment out of time. Like a ground-in punctuation mark closing out a frenetically hand-written confession, it packs a wallop. In contrast, Fuller’s second feature, The Baron of Arizona (1950) is all thumbs, as much a forgery as the one perpetrated by its protagonist James Addison Reavis (Vincent Price). Price can get his freak on with the best of them, and he’s justified in declaring Reavis one of his all-time favorite roles. But his assaying of this charismatic con artist (who creates a detailed rock-paper-people trail that ascribes to he and his heirs full ownership of the state of Arizona) is strangely muted within Fuller’s muddled whole. The Baron of Arizona is a globetrotter, traversing a poverty row-forged path from the United States’ harsh western countryside to a puzzle-box Spanish monastery (where books are chained up for their own protection) and back again. Yet it never attains the hypnotic precision of Fuller’s best work (the psychologically charged sense of a nightmare unfolding), and this despite the presence of master cinematographer James Wong Howe, working for chiaroscuro-evocative scale.

In contrast, Fuller’s second feature, The Baron of Arizona (1950) is all thumbs, as much a forgery as the one perpetrated by its protagonist James Addison Reavis (Vincent Price). Price can get his freak on with the best of them, and he’s justified in declaring Reavis one of his all-time favorite roles. But his assaying of this charismatic con artist (who creates a detailed rock-paper-people trail that ascribes to he and his heirs full ownership of the state of Arizona) is strangely muted within Fuller’s muddled whole. The Baron of Arizona is a globetrotter, traversing a poverty row-forged path from the United States’ harsh western countryside to a puzzle-box Spanish monastery (where books are chained up for their own protection) and back again. Yet it never attains the hypnotic precision of Fuller’s best work (the psychologically charged sense of a nightmare unfolding), and this despite the presence of master cinematographer James Wong Howe, working for chiaroscuro-evocative scale. But Fuller’s next film (the final one in this set) is an indisputable masterpiece. The Steel Helmet (1951) is a fever dream of the Korean War, entirely possessed of its own unique, inimitable rhythms. Gene Evans’ gruff, cigar-chomping Sergeant Zack acts as de facto head of a ragtag assemblage of soldiers and hangers-on only a few steps removed from complete caricature. The film is primarily a series of clashes between skin color, physiognomy, ideology, and attitude, but what separates this from the liberal pieties of lesser filmmakers is Fuller’s masterful abstraction of the landscape in which these confrontations occur. A battle with snipers in a fog-shrouded forest seems to go on for an eternity – it goes past the point of exhaustion to a disquieting place of hyper-awareness. Like a virus, it infects each and every subsequent action so that, say, a booby-trapped explosive packs all the numbing, horrific punch that it should – it’s not merely a punctuating, manipulative grace note; it resonates with all that has come before and all that is yet to be.

But Fuller’s next film (the final one in this set) is an indisputable masterpiece. The Steel Helmet (1951) is a fever dream of the Korean War, entirely possessed of its own unique, inimitable rhythms. Gene Evans’ gruff, cigar-chomping Sergeant Zack acts as de facto head of a ragtag assemblage of soldiers and hangers-on only a few steps removed from complete caricature. The film is primarily a series of clashes between skin color, physiognomy, ideology, and attitude, but what separates this from the liberal pieties of lesser filmmakers is Fuller’s masterful abstraction of the landscape in which these confrontations occur. A battle with snipers in a fog-shrouded forest seems to go on for an eternity – it goes past the point of exhaustion to a disquieting place of hyper-awareness. Like a virus, it infects each and every subsequent action so that, say, a booby-trapped explosive packs all the numbing, horrific punch that it should – it’s not merely a punctuating, manipulative grace note; it resonates with all that has come before and all that is yet to be. The Steel Helmet’s primary location is, fittingly, an abandoned temple that the soldiers attempt to fortify. But even with the presence of a literal deity (a passive-aggressive statue of Buddha), God is entirely absent from this place. The men argue over menial tasks, engage in casual racism and impromptu discussions of same (in this respect, Fuller was way ahead of his time, practically predicting the progress made by civil rights luminaries like Rosa Parks), but the only certainty in this brute-intellectual hothouse is death, which comes, quickly and gracelessly, on a good many of the inhabitants. The loss of William Chun’s young Korean tag-along Short Round (no doubt an inspiration for Steven Spielberg, who owes a mostly unexplored aesthetic debt to Fuller, especially in The Steel Helmet-reminiscent War of the Worlds, similarly a tale of battle-scarred survivors) drives Sergeant Zack over the edge, though his madness, for all its outward aggression, is in no way physically debilitating. Perhaps this is the ultimate tragedy for Fuller: that despite the many horrors we witness and experience, our bodies so rarely allow us respite from the everyday grind. To some, this might be a prevailing example of the indomitability of the human spirit, but Fuller’s cinema, for all its life, for all its bravado, possesses a troublingly antithetical undercurrent, a resolute desire – on the part of its characters and, perhaps, of their Creator – to escape into the pure, unencumbered bliss of insanity.

The Steel Helmet’s primary location is, fittingly, an abandoned temple that the soldiers attempt to fortify. But even with the presence of a literal deity (a passive-aggressive statue of Buddha), God is entirely absent from this place. The men argue over menial tasks, engage in casual racism and impromptu discussions of same (in this respect, Fuller was way ahead of his time, practically predicting the progress made by civil rights luminaries like Rosa Parks), but the only certainty in this brute-intellectual hothouse is death, which comes, quickly and gracelessly, on a good many of the inhabitants. The loss of William Chun’s young Korean tag-along Short Round (no doubt an inspiration for Steven Spielberg, who owes a mostly unexplored aesthetic debt to Fuller, especially in The Steel Helmet-reminiscent War of the Worlds, similarly a tale of battle-scarred survivors) drives Sergeant Zack over the edge, though his madness, for all its outward aggression, is in no way physically debilitating. Perhaps this is the ultimate tragedy for Fuller: that despite the many horrors we witness and experience, our bodies so rarely allow us respite from the everyday grind. To some, this might be a prevailing example of the indomitability of the human spirit, but Fuller’s cinema, for all its life, for all its bravado, possesses a troublingly antithetical undercurrent, a resolute desire – on the part of its characters and, perhaps, of their Creator – to escape into the pure, unencumbered bliss of insanity.

Maybe that’s what movies are for. Image/Sound/Extras: Each film in “The First Films of Samuel Fuller” box set is presented in its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio, slightly pictureboxed to compensate for television overscan. For a more detailed discussion of this, in some circles, controversial practice, see DVDBeaver webmaster Gary Tooze’s discussion in his review of Kind Hearts and Coronets. Relatively, The Baron of Arizona fares worst in the image department, though this has more to do with existing print damage than anything. Per Criterion’s reputation, this is a more than satisfactory visual presentation. Sound on all three films is Dolby Digital mono in the original English, similarly issue-free aside from any source-related defects that more attuned ears may pick up. Per the Eclipse series mission statement, there are no extras included.

Image/Sound/Extras: Each film in “The First Films of Samuel Fuller” box set is presented in its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio, slightly pictureboxed to compensate for television overscan. For a more detailed discussion of this, in some circles, controversial practice, see DVDBeaver webmaster Gary Tooze’s discussion in his review of Kind Hearts and Coronets. Relatively, The Baron of Arizona fares worst in the image department, though this has more to do with existing print damage than anything. Per Criterion’s reputation, this is a more than satisfactory visual presentation. Sound on all three films is Dolby Digital mono in the original English, similarly issue-free aside from any source-related defects that more attuned ears may pick up. Per the Eclipse series mission statement, there are no extras included.

___________________________________________

Keith Uhlich is co-editor of The House Next Door and a contributor to various print and online publications.