By Andrew Chan Despite the persistent belief that great art is driven and justified by an intellectual (rather than emotional or aesthetic) impulse, it is in fact difficult to make a film whose basis is conceptual without the results coming off as simplistic or overly designed. Such films present themselves with the challenge of filtering the world through an idea, a phrase, or even a single word, and ultimately fail if the starting-point diminishes our worldview rather than expanding or complicating it. There are, of course, some outstanding examples of films that wear their thematic concerns on their sleeves while also succeeding as art, one being Kieslowski’s Decalogue, which addressed the limits of its approach by embracing and revising the old form of the parable. Another example would be the major films of Agnès Varda, which employ a mode of storytelling that launches from ideas, or from the rickety language we use to encapsulate ideas, and risks the theoretical and the literary in order to achieve (at its best) a beautifully nuanced metacinema. With the Faulkner-inspired structure of La Pointe Courte, the real-time experiment of Cléo from 5 to 7, and the explorations of one-word concepts (“happiness” and “gleaning”) in Le Bonheur and The Gleaners and I, Varda encourages her audience to question the ways in which movies construct, interrupt, and sometimes collapse the narratives and meanings they put forth.

Despite the persistent belief that great art is driven and justified by an intellectual (rather than emotional or aesthetic) impulse, it is in fact difficult to make a film whose basis is conceptual without the results coming off as simplistic or overly designed. Such films present themselves with the challenge of filtering the world through an idea, a phrase, or even a single word, and ultimately fail if the starting-point diminishes our worldview rather than expanding or complicating it. There are, of course, some outstanding examples of films that wear their thematic concerns on their sleeves while also succeeding as art, one being Kieslowski’s Decalogue, which addressed the limits of its approach by embracing and revising the old form of the parable. Another example would be the major films of Agnès Varda, which employ a mode of storytelling that launches from ideas, or from the rickety language we use to encapsulate ideas, and risks the theoretical and the literary in order to achieve (at its best) a beautifully nuanced metacinema. With the Faulkner-inspired structure of La Pointe Courte, the real-time experiment of Cléo from 5 to 7, and the explorations of one-word concepts (“happiness” and “gleaning”) in Le Bonheur and The Gleaners and I, Varda encourages her audience to question the ways in which movies construct, interrupt, and sometimes collapse the narratives and meanings they put forth.

In 1985’s Vagabond, which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and is still probably her masterpiece, Varda’s affinity for the conceptual manifests itself both stylistically and thematically. But her career-long suspicion of any conclusive vérité that might be extracted from cinema makes for a film that revolves around ambiguities and questions rather than big statements; in fact, Varda goes so far as to remind us of this early on with a shot of a red question mark painted on the wall of a building. Like La Pointe Courte and Cléo from 5 to 7, Vagabond operates on a structural gimmick; evoking Citizen Kane, Rashomon, and (according to Varda) the experimental novels of Nathalie Sarraute, the film sets out to reconstruct the life of a dead woman named Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire) through a series of rambling flashbacks punctuated by uniformly terse, direct-to-camera testimonies from people who were acquainted with her. Found frozen to death in a ditch in the opening scene, Mona is revived as a subject for investigation. We learn that she was a drifter but are only given clues to her former life as a typist and vocational school drop-out; we discover nothing of where she used to live or the family she has run away from. As the film moves from scenario to scenario, we meet men who found her sexually unyielding, overly idealistic, or unappreciative of their charity; and women who were fascinated or repulsed by (or even jealous of) her complete disregard for social norms. Highlights among these characters include a hippie who gives Mona shelter; an agronomist who takes her on as a kind of sociological project; a Tunisian migrant worker who promises to take care of her; and a maid who views her as a romantic figure capable of drawing out passion in men. In this tangle of flimsy interpretations, Mona hardens into a new cinematic archetype: a young female rebel who is genuinely without a cause. But neither Varda nor her audience is capable of summoning interpretations that are not ideological or poetic, even though Mona’s journey is strictly non-ideological and non-poetic. We are led back to the devastating old cliché that nothing and no one can be fully known, since knowledge is dependent on competing subjectivities.

Found frozen to death in a ditch in the opening scene, Mona is revived as a subject for investigation. We learn that she was a drifter but are only given clues to her former life as a typist and vocational school drop-out; we discover nothing of where she used to live or the family she has run away from. As the film moves from scenario to scenario, we meet men who found her sexually unyielding, overly idealistic, or unappreciative of their charity; and women who were fascinated or repulsed by (or even jealous of) her complete disregard for social norms. Highlights among these characters include a hippie who gives Mona shelter; an agronomist who takes her on as a kind of sociological project; a Tunisian migrant worker who promises to take care of her; and a maid who views her as a romantic figure capable of drawing out passion in men. In this tangle of flimsy interpretations, Mona hardens into a new cinematic archetype: a young female rebel who is genuinely without a cause. But neither Varda nor her audience is capable of summoning interpretations that are not ideological or poetic, even though Mona’s journey is strictly non-ideological and non-poetic. We are led back to the devastating old cliché that nothing and no one can be fully known, since knowledge is dependent on competing subjectivities.

While the Welles of the ’40s and Kurosawa of the ’50s were a little too pleased with their innovations, directing as if they were the first filmmakers to discover truth’s slipperiness, Varda’s own take on this classic multi-POV structure shows ease and mastery worth those intervening decades. Vagabond begins creakily with Varda as narrator, already mythologizing Mona as some magical creature from the sea; one would be forgiven for anticipating a control-freak of an auteur who won’t stop flaunting her own devices. But the voice-over is dispensed with, and Varda’s grip on the material becomes looser, as if to match the grunginess of her anti-heroine. As she contrasts the overlapping truths emerging from her eccentric cast of characters (most of whom are played by non-professional actors), our attention is directed away from intellectualizing Mona’s splintered identity to experiencing it. Varda’s concept-driven style remains fluid; it rarely overstates itself, and exhibits the director’s willingness to step back and let Bonnaire’s remarkable performance embody not just ideas but also a credible, fascinating, individual self. Despite the faultiness of truth, the film allows for the fact that someone actual is being resurrected here; in a sense, cinema makes real; and the truths about Mona that have been omitted or obscured are no greater than truths omitted and obscured in the constraints of any fiction or non-fiction narrative. In the wild eyes of a precocious actress (Bonnaire was only seventeen at the time of production), Mona’s doom, charisma, and affected dispassion take on a documentary-like authenticity, comparable to legendary direct-from-the-streets performances such as Fernando Ramos de Silva in Pixote. The major theme of Vagabond turns out to be another concept: freedom. (The film would make an interesting double feature with Kieslowski’s upper-class Blue.) The cost of being completely free of society’s expectations, the pain of relationships, and the boredom of work is being, in the end, completely alone. It is clear not only that Mona has liberated herself from the drudgery of what she saw as limited, quotidian options, but also that she is free from making the sacrifices domestic women are forced to make when they marry men. In the ’80s, the phenomenon of “homeless and lawless” women (in the words of the film’s French title, Sans toit ni loi) was still quite new in France. Varda makes a distinction between the reactions Mona receives from the different genders; men, on their motorcycles and in their trucks, often look past Mona’s filth and see a potential sex object, while women see a possibly feminist pioneer who fends for herself in a male world. The film is, on the one hand, repulsed by Mona’s unladylike filth (the camera catches her cleaning out her nose on more than one occasion) and her rejection of all things passionate and interpersonal, but on the other hand, it can’t help but celebrate her almost pious reduction to an elemental existence. This sympathy arises in spite of the fact that Mona never becomes a sympathetic character.

The major theme of Vagabond turns out to be another concept: freedom. (The film would make an interesting double feature with Kieslowski’s upper-class Blue.) The cost of being completely free of society’s expectations, the pain of relationships, and the boredom of work is being, in the end, completely alone. It is clear not only that Mona has liberated herself from the drudgery of what she saw as limited, quotidian options, but also that she is free from making the sacrifices domestic women are forced to make when they marry men. In the ’80s, the phenomenon of “homeless and lawless” women (in the words of the film’s French title, Sans toit ni loi) was still quite new in France. Varda makes a distinction between the reactions Mona receives from the different genders; men, on their motorcycles and in their trucks, often look past Mona’s filth and see a potential sex object, while women see a possibly feminist pioneer who fends for herself in a male world. The film is, on the one hand, repulsed by Mona’s unladylike filth (the camera catches her cleaning out her nose on more than one occasion) and her rejection of all things passionate and interpersonal, but on the other hand, it can’t help but celebrate her almost pious reduction to an elemental existence. This sympathy arises in spite of the fact that Mona never becomes a sympathetic character.

Even more urgent than the film’s ideas on freedom is this question of sympathy, which is a sly but forceful implication of the audience. The film implicitly asks: What qualities are required for a person to be deserving of other people’s compassion? The same question was hurled last year at the Thoreau-wannabe in Into the Wild, another willfully irresponsible outcast who, one might argue, also brought tragedy on himself. But Vagabond is much less romantic and transcendent than that film, or almost any other film about drifters that has followed it. With dirt-colored cinematography, prickly textures, and an eerie violin score that mimics a lacerating wind, it rarely gives us refuge from the harshness of its exteriors; it seems that few films have ever been set at such a merciless physical and emotional temperature. When we first see Mona’s dead body in this dead landscape, our impulse is to search for the victim, the martyr, or the symbol in her. But we can’t pity her the way we do Lars von Trier’s put-upon stoics; we learn soon enough that she’s an unapologetic nihilist who has no interest in saving herself, let alone the world. What place does our compassion and charity take in this story? How do we explain her motivations to ourselves? Is she responsible for the choices she makes in a world that seems to be without real choices? Can we dismiss her as the product of social oppression or psychological illness, or do we find pieces of our most fundamental fears and longings in her? These questions go to the heart of how poverty, pain, and filth continue to be moralized in our society. Vagabond, one of Varda’s most shrewdly political films, recognizes the privileged position cinema places us in by offering entire lives up to our scrutiny. It makes itself equal to such a responsibility. The film’s great achievement is a character who repeatedly confounds our most ingrained senses of judgment.

But we can’t pity her the way we do Lars von Trier’s put-upon stoics; we learn soon enough that she’s an unapologetic nihilist who has no interest in saving herself, let alone the world. What place does our compassion and charity take in this story? How do we explain her motivations to ourselves? Is she responsible for the choices she makes in a world that seems to be without real choices? Can we dismiss her as the product of social oppression or psychological illness, or do we find pieces of our most fundamental fears and longings in her? These questions go to the heart of how poverty, pain, and filth continue to be moralized in our society. Vagabond, one of Varda’s most shrewdly political films, recognizes the privileged position cinema places us in by offering entire lives up to our scrutiny. It makes itself equal to such a responsibility. The film’s great achievement is a character who repeatedly confounds our most ingrained senses of judgment.

Image/Sound/Extras: The fourth disc in The Criterion Collection’s generous and eye-opening set 4 by Agnès Varda, this is an update of an extra-less version the company released in 2000. Image and sound are as immaculate as one would expect from a new high-definition digital transfer supervised by the director herself. The illuminating essay included with the package, written by critic Chris Darke, is a vast improvement on the one by Sandy Flitterman-Lewis found in the earlier edition. But the real highlights here are a new bounty of supplements: these include the forty-minute making-of documentary Remembrances, in which we get to see an older, shockingly glamorous Sandrine Bonnaire; a brief interview with composer Joanna Bruzdowicz followed by a back-to-back presentation of all the film’s dolly shots; a 1986 radio interview that explains why Varda dedicated the film to the French novelist Nathalie Sarraute and which suggests a kinship between these two underappreciated, groundbreaking female artists; and, perhaps best of all, a short tribute, in much-degraded 16mm, to the charming actress Marthe Jarnais.

Andrew Chan is a poet and film critic currently studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the creator of the blog Movie Love.

Monday, January 1, 2007

The Criterion Collection #74: Vagabond

The Criterion Collection #73: Cléo from 5 to 7

By Andrew Chan Agnès Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7, the film that put the “Grandmother of the French New Wave” on the international map, follows a pop singer (Corinne Marchand) through the streets of Paris as she awaits medical results that will report the severity of her cancer. Captured in approximate real time, her journey begins in a fortune teller’s office; within minutes, a foreboding tarot reading has her convinced she’s done for. But the film that follows is never chained to the heroine’s sense of impending doom. From start to finish, Cléo is a remarkably tonic portrait of urban anxiety, the sloth of the privileged, and the hazards of day-to-day, hour-to-hour living. Usually identified with the more serious and radical Left Bank division of the New Wave (which also included Alain Resnais and Chris Marker), Varda adopts the free-spirited attitude of Truffaut and Godard’s earliest popular successes, resulting in a film that is both a study in stylistic possibilities and a valentine to urban life.

Agnès Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7, the film that put the “Grandmother of the French New Wave” on the international map, follows a pop singer (Corinne Marchand) through the streets of Paris as she awaits medical results that will report the severity of her cancer. Captured in approximate real time, her journey begins in a fortune teller’s office; within minutes, a foreboding tarot reading has her convinced she’s done for. But the film that follows is never chained to the heroine’s sense of impending doom. From start to finish, Cléo is a remarkably tonic portrait of urban anxiety, the sloth of the privileged, and the hazards of day-to-day, hour-to-hour living. Usually identified with the more serious and radical Left Bank division of the New Wave (which also included Alain Resnais and Chris Marker), Varda adopts the free-spirited attitude of Truffaut and Godard’s earliest popular successes, resulting in a film that is both a study in stylistic possibilities and a valentine to urban life.

Varda has stated that Cléo marked the first time she was able to reconcile her interest in the artificial, reconstructive properties of film with the medium’s capacity for authentically documenting the real world. This tension between the natural and the fabricated echoes not only in Varda’s stylistic flourishes (her idiosyncratic editing; her thrilling mixtures of genre) but also in the personality and predicament of her title character. Has there ever been a tragic heroine as unimposing as Cléo, or a depiction of illness as deliberately on-the-surface as in this film? Varda commits her first transgression by setting Cléo during what she admits are the raciest two hours in everyday French life, that period typically set aside for an evening roll in the hay. The film departs from our expectations of how the ill should be represented onscreen, the departure being particularly jarring because Varda introduces that weighty word “cancer” right off the bat. The audience’s immediate desire is to sympathize with Cléo, to heroize her, and to be helped along by some wholesome, old-fashioned melodrama. Instead, we find Cléo concerned about her potential loss of youth and beauty, constantly staring at herself in the endless hall of mirrors formed by the shop windows of Paris. Soon enough, we find her concerns pushed to the film’s margins time and again by more frivolous attractions. By surrounding Cléo in an environment of blithe obliviousness, Varda would have us convinced that the central drama here—the gut-wrenching anticipation of destiny; the misfortune of a possibly premature death—is of no real import. This unsentimental strategy allows us to discern one of the central issues laid out in the film, which concerns the rules of public emotional display. How does a film (or a person) weigh private fears against the social (and even political) priorities of the world? In one scene, Cléo walks into a restaurant for the sole purpose of playing her latest song on the jukebox to gauge the customers’ (largely indifferent) reactions. Moments later, she is riding in a taxi, hearing celebrity news about the recovery of Édith Piaf from surgery, and world news about the Algerian conflict. In this clever juxtaposition of audio, we are confronted with the fundamentally feminist question of where an individual woman’s anxieties stand in the grand scale of a busy, tragic world, as well as the humanist question of how we look outside ourselves without our personal suffering being illegitimated.

By surrounding Cléo in an environment of blithe obliviousness, Varda would have us convinced that the central drama here—the gut-wrenching anticipation of destiny; the misfortune of a possibly premature death—is of no real import. This unsentimental strategy allows us to discern one of the central issues laid out in the film, which concerns the rules of public emotional display. How does a film (or a person) weigh private fears against the social (and even political) priorities of the world? In one scene, Cléo walks into a restaurant for the sole purpose of playing her latest song on the jukebox to gauge the customers’ (largely indifferent) reactions. Moments later, she is riding in a taxi, hearing celebrity news about the recovery of Édith Piaf from surgery, and world news about the Algerian conflict. In this clever juxtaposition of audio, we are confronted with the fundamentally feminist question of where an individual woman’s anxieties stand in the grand scale of a busy, tragic world, as well as the humanist question of how we look outside ourselves without our personal suffering being illegitimated.

Whenever Varda decides to bring on the old-school heartache, she does so using the most transparently artificial means. On the rare occasions that we are allowed to plunge into Cléo’s psyche, we either hear her thoughts in voiceover, or experience her fear through a series of jump-cuts. The first time Cléo breaks into tears is exactly the point at which the film’s emotional expression and its transparency as film collide. In one of the most astonishing scenes, the camera starts off observing Cléo at rehearsal, slides in to frame her in the manner of a musical number, then quickly zooms out to jerk the audience back into the film’s “standard” layer of reality. Real-time structure always positions a movie at the center of cinema’s oldest genre division: the split between documentary and fiction which Varda has mined throughout her career. Approximations of “real time” in movies are usually undertaken with the intent of establishing a heightened reality. But attempts at this challenging stunt are few because, no matter how realistic cinema may pretend to be, it always exists in a separate universe, one whose sense of time moves according to the characters’ emotions or the director’s idea of what will keep an audience interested. As a gimmick, real time holds such fascination precisely because it is so confused about what it wants to achieve: while in theory it strives for slice-of-life naturalism, in actuality it can never divorce itself from the wish to be audacious, pyrotechnic, virtuosic—the same wish that, to a certain extent, underlies all our notions about the magic of cinema.

Real-time structure always positions a movie at the center of cinema’s oldest genre division: the split between documentary and fiction which Varda has mined throughout her career. Approximations of “real time” in movies are usually undertaken with the intent of establishing a heightened reality. But attempts at this challenging stunt are few because, no matter how realistic cinema may pretend to be, it always exists in a separate universe, one whose sense of time moves according to the characters’ emotions or the director’s idea of what will keep an audience interested. As a gimmick, real time holds such fascination precisely because it is so confused about what it wants to achieve: while in theory it strives for slice-of-life naturalism, in actuality it can never divorce itself from the wish to be audacious, pyrotechnic, virtuosic—the same wish that, to a certain extent, underlies all our notions about the magic of cinema.

The most famous examples of real-time experimentation have a decidedly non-naturalistic effect: Hitchcock’s Rope looks staged; Sokurov’s Russian Ark is sublime and hallucinatory; Linklater’s Before Sunset practically swoons as each second passes by. As in life, the typical film takes time’s passage for granted. But in real time, that passage is isolated and can become more entrancing than even the visual, spatial or aural qualities of a film. In Cléo, Varda invokes the concepts of realism and naturalism implicit in the use of real time, but she also does everything in her power to challenge them by slicing up the flow of time with her sometimes startling edits, and saving the film’s longest takes for the end so that they feel like a breath of fresh air, or a sigh of relief. Cléo moves in sections, with each new chapter title announcing not just the starting but also the ending time of a sequence. This formalist gesture attempts to toll us back to our conception of the film as an exercise in realism. But the principal delight is in watching Varda break her own rules. She has never been a minimalist, and far from being an attempt at “pure,” aesthetically chastened cinema, this film makes its audience aware of the many tools that lie at a director’s disposal. Beginning with the transition from color to black-and-white in the film’s first chapter, we are made conscious of the wide assortment of tricks being played, and as Varda adds on fractured editing, Michel Legrand’s lovely score, claustrophobic art direction, and collage-like bits of sound design, we get the sense that each moviemaking mechanism constitutes another layer of (or an additional distance from) reality. As much as Breathless or Shoot the Piano Player, Cléo is built on a relationship to movie-loving culture. Not only does the film feature cameos from Godard and Anna Karina, but these appearances occur in their very own set-piece: a film within the film. The mounting joy we feel in the final scenes is plugged directly into our cinephilia, as the film becomes reminiscent of great movies that were made before it (particularly Murnau’s Sunrise and Minnelli’s The Clock) and after it (Before Sunset).

Cléo moves in sections, with each new chapter title announcing not just the starting but also the ending time of a sequence. This formalist gesture attempts to toll us back to our conception of the film as an exercise in realism. But the principal delight is in watching Varda break her own rules. She has never been a minimalist, and far from being an attempt at “pure,” aesthetically chastened cinema, this film makes its audience aware of the many tools that lie at a director’s disposal. Beginning with the transition from color to black-and-white in the film’s first chapter, we are made conscious of the wide assortment of tricks being played, and as Varda adds on fractured editing, Michel Legrand’s lovely score, claustrophobic art direction, and collage-like bits of sound design, we get the sense that each moviemaking mechanism constitutes another layer of (or an additional distance from) reality. As much as Breathless or Shoot the Piano Player, Cléo is built on a relationship to movie-loving culture. Not only does the film feature cameos from Godard and Anna Karina, but these appearances occur in their very own set-piece: a film within the film. The mounting joy we feel in the final scenes is plugged directly into our cinephilia, as the film becomes reminiscent of great movies that were made before it (particularly Murnau’s Sunrise and Minnelli’s The Clock) and after it (Before Sunset).

Lying underneath the film’s ostensible obsession with time is Varda’s carefree, pleasurable pacing. Where real time rendered Hitchcock stilted, it made Varda jazzier, certainly freer and more associative than in her carefully scripted debut, La Pointe Courte. Cléo shuffles along leisurely, big-hearted and receptive to all the distractions that come its way, at times falling into some of the most rapturous moments to be found in the Varda canon. Marchand’s performance hits its peak when Cléo, in her first moment of complete solitude, descends a set of stairs toward a park, singing and puckering her lips like the star of her own revue. In this late scene, we understand for the first time that—as much as Cléo’s outwardly driven personality and hunger for attention have been influenced by a culture that demands women be image-conscious—our heroine is also, at the end of the day, a natural born performer. Cléo isn’t the prototypical feminist classic chronicling a woman’s journey from submissiveness to assertiveness, or from silence to self-articulation. The film spends much of its time insisting upon its heroine’s superficiality, refusing to ennoble her even as she carries the burden of a ready-made martyr. The beauty of her ultimate revelation is that, even though it results from an encounter with romance, it occurs modestly, without an ecstatic climax. Throughout the movie we’ve seen Cléo do nothing but perform and act out, so what strikes us most about this ending is her non-performing, and the fact that Varda and Marchand feel no need to compensate for her by bestowing the external markers of a wise, liberated female. Cléo and her true feelings remain mysterious and amorphous, breaking with a long tradition of histrionic silver-screen sufferers. In a film possessed of such youthful, quintessentially New Wave faith in the powers of cinematic style and technique, the director’s vision falls on the side of what cannot be filmed, or even said. Cléo—at the brink of what could be true love—finally stands on her own, proving herself to no one, including the film’s audience.

Cléo isn’t the prototypical feminist classic chronicling a woman’s journey from submissiveness to assertiveness, or from silence to self-articulation. The film spends much of its time insisting upon its heroine’s superficiality, refusing to ennoble her even as she carries the burden of a ready-made martyr. The beauty of her ultimate revelation is that, even though it results from an encounter with romance, it occurs modestly, without an ecstatic climax. Throughout the movie we’ve seen Cléo do nothing but perform and act out, so what strikes us most about this ending is her non-performing, and the fact that Varda and Marchand feel no need to compensate for her by bestowing the external markers of a wise, liberated female. Cléo and her true feelings remain mysterious and amorphous, breaking with a long tradition of histrionic silver-screen sufferers. In a film possessed of such youthful, quintessentially New Wave faith in the powers of cinematic style and technique, the director’s vision falls on the side of what cannot be filmed, or even said. Cléo—at the brink of what could be true love—finally stands on her own, proving herself to no one, including the film’s audience.

Image/Sound/Extras: Updating an earlier Criterion edition issued in 2000, this new DVD of Cléo from 5 to 7 (available only as part of the magnificent package 4 by Agnès Varda) features a restored digital transfer, as well as the set’s largest treasure trove of supplementary material. A good portion of these extras are dedicated to emphasizing the film’s intimate sense of place. In one 35-minute featurette, Varda interviews Corinne Marchand and Antoine Bourseiller at the locations seen in the final sequences of the film. In another, we are offered a swift trip by motorcycle through present-day Paris, recreating Cléo’s 90-minute journey through the city. The disc’s most amusing curio is an excerpt from a 1993 French TV interview, in which Varda praises Madonna’s “natural” acting ability, and the pop-star herself explains why she pursued the role of Cléo in an American remake that never got off the ground.

Inexplicably buried at the bottom of the DVD cover’s list of special features, Varda’s 1958 short film L’opéra Mouffe is actually one of the best discoveries the entire box-set has to offer. Introducing itself as a diary of the everyday impressions of a pregnant woman, the film (which is silent except for its musical soundtrack) succeeds as both poem and document. Scenes of naked young lovers in bed and the elderly in Paris’ Rue Mouffetarde market are mixed with astonishing images, associations, and analogies—a huge melon being hollowed out; a baby chick wriggling in a broken light bulb—that evoke both the miraculousness and awkwardness of birth. Perhaps Varda’s numerous short films deserved a fifth disc all to themselves; L’opéra surely warrants its own essay in the collection’s accompanying booklet, not only for the way it suggests Varda’s other vocations as a photojournalist and an installation artist, but also for its rare, personal take on a specifically female experience. As in much of her earlier work, the gravity of Varda’s subject is offset by a surprising lightness and humor, made possible by a director absorbed as much in the local charms of her film’s setting as she is in her own thoughts.

Andrew Chan is a poet and film critic currently studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the creator of the blog Movie Love.

The Criterion Collection #50: And the Ship Sails On

By Kevin B. Lee & Michael Joshua Rowin [Editor's Note: And the Ship Sails On is part of Kevin B. Lee's ongoing quest to see every title on the list of the 1000 Greatest Films compiled by They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?. His original entry on the film can be found at his blog Shooting Down Pictures. Kevin collaborated with film critic Michael Joshua Rowin to produce a video essay (accessible below) on the film. What follows is the full transcript of their conversation.]

[Editor's Note: And the Ship Sails On is part of Kevin B. Lee's ongoing quest to see every title on the list of the 1000 Greatest Films compiled by They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?. His original entry on the film can be found at his blog Shooting Down Pictures. Kevin collaborated with film critic Michael Joshua Rowin to produce a video essay (accessible below) on the film. What follows is the full transcript of their conversation.]

KEVIN B. LEE: And the Ship Sails On is one of the last of Federico Fellini’s films, made at the twilight of his career. A lot of critics and even Fellini aficionados don’t give this film its full due; they see it as a morbid take on a past era, shot in morose shades of grey without the kind of elaborate camerawork and carnivalesque air that you find in his 60s films. We’re going to talk about a few of the things that we’ve picked up on in this movie that really make it stand out and worth considering.

Making Music without Rota KL: And the Ship Sails On happens to be the first film that Fellini had made without his longtime collaborator, the legendary composer Nino Rota. Which presents an irony since the film seems so preoccupied with the theme of music and examining music in all its power and mystery over people.

KL: And the Ship Sails On happens to be the first film that Fellini had made without his longtime collaborator, the legendary composer Nino Rota. Which presents an irony since the film seems so preoccupied with the theme of music and examining music in all its power and mystery over people.

MICHAEL JOSHUA ROWIN: It’s an interesting aspect and I think in a way you can say that Fellini used opera as a way to get around the fact that he wasn’t working with Nino Rota for the first time. But it’s also a tribute to Nino Rota -- there are all sorts of different forms of music here: Serbian dance music, opera, carnivalesque water music, industrial sounds, and all sorts of interesting textures and tones going on. And that’s something that Nino Rota did for Fellini -- he combined muzaky lounge music with classical components, with great symphony scores for his films, and he made music a key component in his films, from La Strada where a musical refrain is a beautifully haunting motif, to Orchestral Rehearsal where music is the central theme. So in a way the film is a tribute to all Rota had done to bringing a powerful element to the Fellini universe.

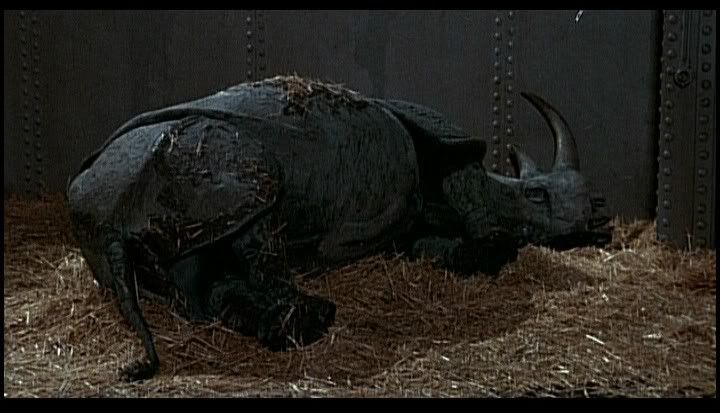

Boiler Room Opera KL: This film is very much about the operatic aesthetic. Plotwise the film is about a group of opera singers who are taking a cruise to dispatch the remains of a legendary diva. On this boat we get a sense of opera under different perspectives, as an embodiment of high and low culture, something that applies to Fellini’s films as well, since his films aspire to artistic stature but also have a heavy degree of carnivalesque lowbrow elements that he really loves.

KL: This film is very much about the operatic aesthetic. Plotwise the film is about a group of opera singers who are taking a cruise to dispatch the remains of a legendary diva. On this boat we get a sense of opera under different perspectives, as an embodiment of high and low culture, something that applies to Fellini’s films as well, since his films aspire to artistic stature but also have a heavy degree of carnivalesque lowbrow elements that he really loves.

MJR: What you were just saying was one of Fellini’s hallmarks. Take the scene where the workers in the boiler room goad the opera singers into a singing contest. The room compositionally dwarfs the characters. We have a lot of long shots where the boiler itself makes the characters small and puny.

KL: He establishes this vertical space where the opera singers are looking down and the laborers are looking up, which implies that the singers have this authority over the boiler room workers. But they’re in competition with each other. Fellini likes to cut horizontally between the singers, and they’re looking at each other jealously. Whereas the boiler room workers are almost always shown as one group, swaying in unison while listening to the singers above. MJR: Fellini cuts to the different singers in close up. He gets closer and closer to them. In the past he used tracking shots to seek his characters out. Here he’s dividing them. Most of the film takes place in long shots which is very different from the usual Fellini aesthetic.

MJR: Fellini cuts to the different singers in close up. He gets closer and closer to them. In the past he used tracking shots to seek his characters out. Here he’s dividing them. Most of the film takes place in long shots which is very different from the usual Fellini aesthetic.

KL: Which I guess is a nod towards the theatrical tradition.

MJR: There’s a great contrast between the high art aesthetic of opera and the ridiculous hyperbolic caricatures that Fellini gets out of these close-up shots of these opera singers doing their damnedest to outdo each other and to win the workers’ favor. It’s very comic and irreverent. I think that’s the main thing about Fellini’s take on high art. He usually likes spoiling it with really crude jokes.

KL: And the fact that it’s in the boiler room and these highly trained baritones and sopranos are singing their lungs out in the midst of this very noisy boiler room…

A Carnival of Sounds MJR: There’s many kinds of sounds working in this film, it’s not just opera. We have industrial clanging sounds, we have the chicken scene, a singing that borders on the hypnotic, we have this music done with glasses, we have Serbian folk music, so Fellini is combining a lot of different sounds and music and tones in this film.

MJR: There’s many kinds of sounds working in this film, it’s not just opera. We have industrial clanging sounds, we have the chicken scene, a singing that borders on the hypnotic, we have this music done with glasses, we have Serbian folk music, so Fellini is combining a lot of different sounds and music and tones in this film.

KL: The film emerges as this extended study of the nature of music as an art form and as a primal mysterious force with strange powers over the human mind…

MJR: I think that’s why Fellini at times is hard to pin down. He can be a political filmmaker, a social observer and so on, but a lot of his ideas are mystical -- I don’t want to say New Age -- but they’re irrational. They try to deal with the transcendent, the ludicrous, the unexplainable. Take the scene with the classical musicians playing music with stemware. It’s very eerie and mysterious, but it’s also funny. It’s a carnivalesque, vaudeville performance, with these upper class artistes who are engaging in something that you would see at a circus.

KL: It’s a weird mix of these technically gifted musicians who are able to apply their talents to make lowbrow music out of these glasses. It’s a weird mix of highbrow skill and lowbrow entertainment.

Highbrow Art and Lowbrow Entertainment MJR: That’s what’s so great about Fellini to me. He’s a filmmaker who emerged during this great wave of European art films and so much of his cinema was experimental, and narratively stylistically unconventional. And yet he was totally unafraid to give us some simple and delightful entertainments.

MJR: That’s what’s so great about Fellini to me. He’s a filmmaker who emerged during this great wave of European art films and so much of his cinema was experimental, and narratively stylistically unconventional. And yet he was totally unafraid to give us some simple and delightful entertainments.

KL: I think about Bergman and the flak that he’s gotten recently. I think Fellini has suffered the same blows by the critical establishment over the years. They aren’t considered highbrow enough -- they’re seen as highbrow entertainers for people who like to think they’re sophisticated in their understanding of cinema, but it’s really these simple, carnivalesque pleasures dressed up in fancy cinematography and symbolism. What do you make of that? MJR: Personally i think that’s unfair. I don’t think that really takes into account how sophisticated Fellini’s vision really was. He was dealing with the high and the low, but not in a way that was middlebrow. He wasn’t catering to any bourgeois populist taste. He definitely struck a nerve, but by this point in his career, after Amarcord he had really fallen out of critical favor. It’s interesting, he still kept on doing what he was doing. But I think, even watching this, and this was a film I had forgotten over time, I found it to be really interesting, just as interesting as Amarcord, which was very popular in its time. And also dark, and melancholic, and touching on all these moods and ideas. There’s so much life to it even though it’s a bleak film in many ways. And just to reduce him to a middle-brow filmmaker is unfair.

MJR: Personally i think that’s unfair. I don’t think that really takes into account how sophisticated Fellini’s vision really was. He was dealing with the high and the low, but not in a way that was middlebrow. He wasn’t catering to any bourgeois populist taste. He definitely struck a nerve, but by this point in his career, after Amarcord he had really fallen out of critical favor. It’s interesting, he still kept on doing what he was doing. But I think, even watching this, and this was a film I had forgotten over time, I found it to be really interesting, just as interesting as Amarcord, which was very popular in its time. And also dark, and melancholic, and touching on all these moods and ideas. There’s so much life to it even though it’s a bleak film in many ways. And just to reduce him to a middle-brow filmmaker is unfair.

KL: After the musicians finish their stemware concert, they start intellectualizing and critiquing the performance they had just finished. Fellini treats it with this gentle mockery, making fun of their seriousness and pretension.

MJR: He recognizes how ridiculous these characters can be, but at the same time he’s not disdainful of their intellectualism. As you see, when they start talking about the Serbian folk music, which is really just an expression of these peoples’ feelings, which comes out of these people’s cultures… Fellini shows the contrast between the pure love of the music by one people, but then he shows them joining in and taking part in it just as the Serbs are. Fellini’s trying to show music as this unifying force which can transcend nationality, race, politics.

Breaking Down Barriers Through Sound and Image KL: In this sequence [where the opera performers dance with the Serbian refugees] we have the same vertical hierarchy as in the boiler room scene, between the bourgeois opera performers who are upstairs and the Serbian refugees downstairs. At the same time it’s a reversal from the boiler room scene…

KL: In this sequence [where the opera performers dance with the Serbian refugees] we have the same vertical hierarchy as in the boiler room scene, between the bourgeois opera performers who are upstairs and the Serbian refugees downstairs. At the same time it’s a reversal from the boiler room scene…

MJR: Because the space collapses between them and the barrier is broken.

KL: Exactly, and it’s the lower classes who are doing the performing and the upper classes are drawn in to their performance.

MJR: This goes back to the idea of spectacle unifying two different groups of people.

KL: There’s a great use of shadow in this scene. The Serbians are mostly seen in shadow, you can’t make out their faces at all. Whereas the people on the upper deck, you can make out each of their faces in detail. But as this hierarchy collapses, you get this blend of seeing people in light and in shadow.

MJR: I wonder if Fellini’s gaze of the Serbs in this scene is a little more exotic, shrouding them in shadow…

KL: More mysterious, more protean in their collective mass movements…

MJR: Blending together…

KL: Yes, very abstract.

MJR: It reminds me of how shadowy the characters are in movies like Satyricon and Casanova where Fellini’s looking at them as some sort of mysterious, unknowable creatures whom he can never really understand as well as the caste he belongs to. KL: To me it gets to the question of human beings as individuals and human beings as collective bodies. You lose what distinguishes you when you join this mass but the mass as so much collective energy that you lose yourself to its power. That’s something that you see in his other films, in these party sequences that are alternately fascinating, seductive and terrifying all at once.

KL: To me it gets to the question of human beings as individuals and human beings as collective bodies. You lose what distinguishes you when you join this mass but the mass as so much collective energy that you lose yourself to its power. That’s something that you see in his other films, in these party sequences that are alternately fascinating, seductive and terrifying all at once.

MJR: They’re subsuming, in a way that allows you to lose yourself in a good way and in a very frightening way. Individual freedom versus mass appeal

KL: It gets to Fellini’s own attitude towards individuality. One of the paradoxes of his films is that they’re considered to be among the most ego-driven because their sensibility is so distinctive. He’s the quintessential artist who imposes his vision on the world. At the same time some of the best moments are these mass sequences with dozens of people and you’re lost in the melee of humanity.

MJR: Even though Fellini usually gives us someone to identify -- for example the Marcello character in La Dolce Vita -- in And The Ship Sails On we have a reporter character who’s our surrogate, but we’re still not sure who to identify with. Identification in Fellini films are very transitory -- it varies depending on the situation. It can completely dissolve.

KL: Some might say that this is the weak point of this film, that there’s no strong figure to identify with. There’s no Mastroianni who’s captivating and glamorous, and you identify with him and enjoy him. It’s more along the lines of Satyricon, where you’re adrift among all these wild things going on, and your attitude towards these events is less anchored.

MJR: What’s interesting is that the heroes in Fellini’s earlier films -- Nights of Cabiria…

KL: La Strada… MJR: Those characters give way to these ciphers who we are really not sure how to feel about, or these weak, reporters who are totally undermined and shown to be ridiculous in their claims to objectivity. And that’s what makes their films interesting or risky.

MJR: Those characters give way to these ciphers who we are really not sure how to feel about, or these weak, reporters who are totally undermined and shown to be ridiculous in their claims to objectivity. And that’s what makes their films interesting or risky.

KL: It’s amazing the turn that Fellini made from the romantic protagonists of the 50s and 60s to these anti-hero pieces in the 70s and 80s. Fellini’s reach can be pretty broad. He’s a filmmaker who likes to embrace different people, and he’s encompassing a lot of different roles that people choose for themselves within this realm of music as a reflection of society. Even with the realm of music you establish a hierarchy between these these highbrow trained musicians and intellectuals, and these Serbian folk whose music is as natural as the air they breathe and they don’t contemplate it as deeply as these intellectuals do, nor do they really have to. One thing that intrigues me about Fellini is that one the one hand he’s such a wide-reaching, wide embracing director, I can’t think of any other director who is as in love with humanity in all its variety, especially its facial and physical variety, some of the most memorable faces are in Fellini movies. At the same time, they all risk edging towards caricature. He has this tendency to illustrate people in terms of their types, which can be limiting at times.

History Aestheticized as Spectacle MJR: One thing that’s interesting about this sequence is that in it, music is unifying two distinct classes of people through their love of music and dance and performance. In previous Fellini films -- and And the Ship Sails On came a decade after Amarcord and Casanova -- he shows that spectacle can create communities that are not joined by love or unification but by fear. So in Amarcord, spectacle, Fascist parades and music and so on are used to bring people under the banner of conformity and mistrust. In Casanova, it’s a complete corruption of the spirit and of love, that create these spectacles that are devoid of any cathartic element, that are really for narcissistic purposes. So it’s interesting in this film, made in 1983, a decade after Amarcord, that Fellini’s view had come around again to a more optimistic, more generous appreciation of what spectacle can do.

MJR: One thing that’s interesting about this sequence is that in it, music is unifying two distinct classes of people through their love of music and dance and performance. In previous Fellini films -- and And the Ship Sails On came a decade after Amarcord and Casanova -- he shows that spectacle can create communities that are not joined by love or unification but by fear. So in Amarcord, spectacle, Fascist parades and music and so on are used to bring people under the banner of conformity and mistrust. In Casanova, it’s a complete corruption of the spirit and of love, that create these spectacles that are devoid of any cathartic element, that are really for narcissistic purposes. So it’s interesting in this film, made in 1983, a decade after Amarcord, that Fellini’s view had come around again to a more optimistic, more generous appreciation of what spectacle can do.

KL: History is reconfigured in these operatic terms. This is a fictionalized historical incident, sort of a melding of the sinking of the Lusitania with the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand, and it’s dealt with by Fellini in a heavily operatic manner. At the end, the way the opera singers evacuate the boat, they make gestures as if they’re about to leave the stage, and the stage itself is on the brink of collapsing as if it was the finale of a Fellini opera.

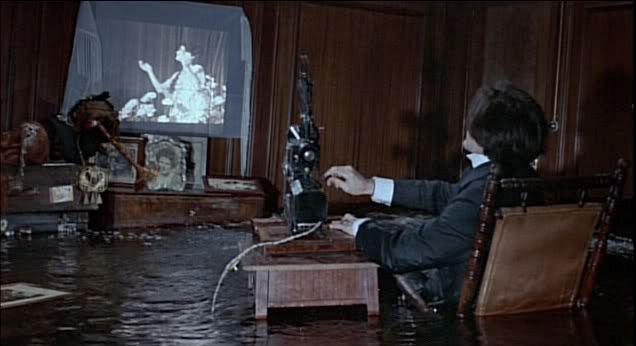

MJR: Everything in this film is highly artificial. The battleship looks unbelievably fake. The sea is made of plastic. And when everyone joins in singing at the end, it’s a climax where the artifice of opera and art renders the historical as an absurd performance piece. And the Ship Sails On is a very pared down film for Fellini in terms of color. It’s very desaturated. Grays and muted greens and blues. And that’s really the palette for the movie. He’s working in very faded tones. The movie starts out in sepia tone and when it goes into color, it’s not like this explosion into color. It’s still very muted. It’s this sort of nostalgic lens through which the film is being regarded. KL: It highly references theater and opera, but at the same time it makes these interesting transitions into cinematic moments,or meta-cinematic moments, where the dead diva is projected on the screen by the conductor…

KL: It highly references theater and opera, but at the same time it makes these interesting transitions into cinematic moments,or meta-cinematic moments, where the dead diva is projected on the screen by the conductor…

MJR: Who’s deeply emotionally attached to her. The whole idea of art as ephemeral, and the technological reproduction of the voice or the image, it’s all a metaphor for the cinema. It’s really Fellini making a statement about cinema through opera in a way. About how artifice almost makes reality both artificial but a greater reality that could ever be lived in in real life.

KL: He’s referencing these artforms that more or less have had their heyday. I wonder if he’s saying the same about cinema. There’s something about this film with its funeral attitude towards cinema… I want to call it a death of cinema film, even as it celebrates cinema’s power -- the penultimate shot in the movie attests to the magic that cinema can construct. Still there’s a sense of profound mourning for the artform as well. Image/Sound/Extras: There once was a time when Criterion packages weren't much to write home about, as evidenced by this lackluster, extra-less disc, first issued in 1999. The non-anamorphic image is grainy (especially in dark scenes); the blues, grays and sepias preferred here by Fellini are more often pallid than luminescent. The mono soundtrack is downright scandalous given that sound and music plays such a heavy part in the film's significance. An accompanying booklet consists of an excerpt from Fellini's autobiography I, Fellini, with scattered musings on the film.

Image/Sound/Extras: There once was a time when Criterion packages weren't much to write home about, as evidenced by this lackluster, extra-less disc, first issued in 1999. The non-anamorphic image is grainy (especially in dark scenes); the blues, grays and sepias preferred here by Fellini are more often pallid than luminescent. The mono soundtrack is downright scandalous given that sound and music plays such a heavy part in the film's significance. An accompanying booklet consists of an excerpt from Fellini's autobiography I, Fellini, with scattered musings on the film.

Video Essay:

____________________________________________________

Kevin B. Lee is a filmmaker based in New York City. He has written for Cinema-Scope, The Chicago Reader, Senses of Cinema and Slant. His website is www.alsolikelife.com.

Michael Joshua Rowin is a staff writer at Reverse Shot. He also writes for L Magazine, Stop Smiling, and runs the blog Hopeless Abandon.