By Kevin B. Lee & Michael Joshua Rowin [Editor's Note: And the Ship Sails On is part of Kevin B. Lee's ongoing quest to see every title on the list of the 1000 Greatest Films compiled by They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?. His original entry on the film can be found at his blog Shooting Down Pictures. Kevin collaborated with film critic Michael Joshua Rowin to produce a video essay (accessible below) on the film. What follows is the full transcript of their conversation.]

[Editor's Note: And the Ship Sails On is part of Kevin B. Lee's ongoing quest to see every title on the list of the 1000 Greatest Films compiled by They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?. His original entry on the film can be found at his blog Shooting Down Pictures. Kevin collaborated with film critic Michael Joshua Rowin to produce a video essay (accessible below) on the film. What follows is the full transcript of their conversation.]

KEVIN B. LEE: And the Ship Sails On is one of the last of Federico Fellini’s films, made at the twilight of his career. A lot of critics and even Fellini aficionados don’t give this film its full due; they see it as a morbid take on a past era, shot in morose shades of grey without the kind of elaborate camerawork and carnivalesque air that you find in his 60s films. We’re going to talk about a few of the things that we’ve picked up on in this movie that really make it stand out and worth considering.

Making Music without Rota KL: And the Ship Sails On happens to be the first film that Fellini had made without his longtime collaborator, the legendary composer Nino Rota. Which presents an irony since the film seems so preoccupied with the theme of music and examining music in all its power and mystery over people.

KL: And the Ship Sails On happens to be the first film that Fellini had made without his longtime collaborator, the legendary composer Nino Rota. Which presents an irony since the film seems so preoccupied with the theme of music and examining music in all its power and mystery over people.

MICHAEL JOSHUA ROWIN: It’s an interesting aspect and I think in a way you can say that Fellini used opera as a way to get around the fact that he wasn’t working with Nino Rota for the first time. But it’s also a tribute to Nino Rota -- there are all sorts of different forms of music here: Serbian dance music, opera, carnivalesque water music, industrial sounds, and all sorts of interesting textures and tones going on. And that’s something that Nino Rota did for Fellini -- he combined muzaky lounge music with classical components, with great symphony scores for his films, and he made music a key component in his films, from La Strada where a musical refrain is a beautifully haunting motif, to Orchestral Rehearsal where music is the central theme. So in a way the film is a tribute to all Rota had done to bringing a powerful element to the Fellini universe.

Boiler Room Opera KL: This film is very much about the operatic aesthetic. Plotwise the film is about a group of opera singers who are taking a cruise to dispatch the remains of a legendary diva. On this boat we get a sense of opera under different perspectives, as an embodiment of high and low culture, something that applies to Fellini’s films as well, since his films aspire to artistic stature but also have a heavy degree of carnivalesque lowbrow elements that he really loves.

KL: This film is very much about the operatic aesthetic. Plotwise the film is about a group of opera singers who are taking a cruise to dispatch the remains of a legendary diva. On this boat we get a sense of opera under different perspectives, as an embodiment of high and low culture, something that applies to Fellini’s films as well, since his films aspire to artistic stature but also have a heavy degree of carnivalesque lowbrow elements that he really loves.

MJR: What you were just saying was one of Fellini’s hallmarks. Take the scene where the workers in the boiler room goad the opera singers into a singing contest. The room compositionally dwarfs the characters. We have a lot of long shots where the boiler itself makes the characters small and puny.

KL: He establishes this vertical space where the opera singers are looking down and the laborers are looking up, which implies that the singers have this authority over the boiler room workers. But they’re in competition with each other. Fellini likes to cut horizontally between the singers, and they’re looking at each other jealously. Whereas the boiler room workers are almost always shown as one group, swaying in unison while listening to the singers above. MJR: Fellini cuts to the different singers in close up. He gets closer and closer to them. In the past he used tracking shots to seek his characters out. Here he’s dividing them. Most of the film takes place in long shots which is very different from the usual Fellini aesthetic.

MJR: Fellini cuts to the different singers in close up. He gets closer and closer to them. In the past he used tracking shots to seek his characters out. Here he’s dividing them. Most of the film takes place in long shots which is very different from the usual Fellini aesthetic.

KL: Which I guess is a nod towards the theatrical tradition.

MJR: There’s a great contrast between the high art aesthetic of opera and the ridiculous hyperbolic caricatures that Fellini gets out of these close-up shots of these opera singers doing their damnedest to outdo each other and to win the workers’ favor. It’s very comic and irreverent. I think that’s the main thing about Fellini’s take on high art. He usually likes spoiling it with really crude jokes.

KL: And the fact that it’s in the boiler room and these highly trained baritones and sopranos are singing their lungs out in the midst of this very noisy boiler room…

A Carnival of Sounds MJR: There’s many kinds of sounds working in this film, it’s not just opera. We have industrial clanging sounds, we have the chicken scene, a singing that borders on the hypnotic, we have this music done with glasses, we have Serbian folk music, so Fellini is combining a lot of different sounds and music and tones in this film.

MJR: There’s many kinds of sounds working in this film, it’s not just opera. We have industrial clanging sounds, we have the chicken scene, a singing that borders on the hypnotic, we have this music done with glasses, we have Serbian folk music, so Fellini is combining a lot of different sounds and music and tones in this film.

KL: The film emerges as this extended study of the nature of music as an art form and as a primal mysterious force with strange powers over the human mind…

MJR: I think that’s why Fellini at times is hard to pin down. He can be a political filmmaker, a social observer and so on, but a lot of his ideas are mystical -- I don’t want to say New Age -- but they’re irrational. They try to deal with the transcendent, the ludicrous, the unexplainable. Take the scene with the classical musicians playing music with stemware. It’s very eerie and mysterious, but it’s also funny. It’s a carnivalesque, vaudeville performance, with these upper class artistes who are engaging in something that you would see at a circus.

KL: It’s a weird mix of these technically gifted musicians who are able to apply their talents to make lowbrow music out of these glasses. It’s a weird mix of highbrow skill and lowbrow entertainment.

Highbrow Art and Lowbrow Entertainment MJR: That’s what’s so great about Fellini to me. He’s a filmmaker who emerged during this great wave of European art films and so much of his cinema was experimental, and narratively stylistically unconventional. And yet he was totally unafraid to give us some simple and delightful entertainments.

MJR: That’s what’s so great about Fellini to me. He’s a filmmaker who emerged during this great wave of European art films and so much of his cinema was experimental, and narratively stylistically unconventional. And yet he was totally unafraid to give us some simple and delightful entertainments.

KL: I think about Bergman and the flak that he’s gotten recently. I think Fellini has suffered the same blows by the critical establishment over the years. They aren’t considered highbrow enough -- they’re seen as highbrow entertainers for people who like to think they’re sophisticated in their understanding of cinema, but it’s really these simple, carnivalesque pleasures dressed up in fancy cinematography and symbolism. What do you make of that? MJR: Personally i think that’s unfair. I don’t think that really takes into account how sophisticated Fellini’s vision really was. He was dealing with the high and the low, but not in a way that was middlebrow. He wasn’t catering to any bourgeois populist taste. He definitely struck a nerve, but by this point in his career, after Amarcord he had really fallen out of critical favor. It’s interesting, he still kept on doing what he was doing. But I think, even watching this, and this was a film I had forgotten over time, I found it to be really interesting, just as interesting as Amarcord, which was very popular in its time. And also dark, and melancholic, and touching on all these moods and ideas. There’s so much life to it even though it’s a bleak film in many ways. And just to reduce him to a middle-brow filmmaker is unfair.

MJR: Personally i think that’s unfair. I don’t think that really takes into account how sophisticated Fellini’s vision really was. He was dealing with the high and the low, but not in a way that was middlebrow. He wasn’t catering to any bourgeois populist taste. He definitely struck a nerve, but by this point in his career, after Amarcord he had really fallen out of critical favor. It’s interesting, he still kept on doing what he was doing. But I think, even watching this, and this was a film I had forgotten over time, I found it to be really interesting, just as interesting as Amarcord, which was very popular in its time. And also dark, and melancholic, and touching on all these moods and ideas. There’s so much life to it even though it’s a bleak film in many ways. And just to reduce him to a middle-brow filmmaker is unfair.

KL: After the musicians finish their stemware concert, they start intellectualizing and critiquing the performance they had just finished. Fellini treats it with this gentle mockery, making fun of their seriousness and pretension.

MJR: He recognizes how ridiculous these characters can be, but at the same time he’s not disdainful of their intellectualism. As you see, when they start talking about the Serbian folk music, which is really just an expression of these peoples’ feelings, which comes out of these people’s cultures… Fellini shows the contrast between the pure love of the music by one people, but then he shows them joining in and taking part in it just as the Serbs are. Fellini’s trying to show music as this unifying force which can transcend nationality, race, politics.

Breaking Down Barriers Through Sound and Image KL: In this sequence [where the opera performers dance with the Serbian refugees] we have the same vertical hierarchy as in the boiler room scene, between the bourgeois opera performers who are upstairs and the Serbian refugees downstairs. At the same time it’s a reversal from the boiler room scene…

KL: In this sequence [where the opera performers dance with the Serbian refugees] we have the same vertical hierarchy as in the boiler room scene, between the bourgeois opera performers who are upstairs and the Serbian refugees downstairs. At the same time it’s a reversal from the boiler room scene…

MJR: Because the space collapses between them and the barrier is broken.

KL: Exactly, and it’s the lower classes who are doing the performing and the upper classes are drawn in to their performance.

MJR: This goes back to the idea of spectacle unifying two different groups of people.

KL: There’s a great use of shadow in this scene. The Serbians are mostly seen in shadow, you can’t make out their faces at all. Whereas the people on the upper deck, you can make out each of their faces in detail. But as this hierarchy collapses, you get this blend of seeing people in light and in shadow.

MJR: I wonder if Fellini’s gaze of the Serbs in this scene is a little more exotic, shrouding them in shadow…

KL: More mysterious, more protean in their collective mass movements…

MJR: Blending together…

KL: Yes, very abstract.

MJR: It reminds me of how shadowy the characters are in movies like Satyricon and Casanova where Fellini’s looking at them as some sort of mysterious, unknowable creatures whom he can never really understand as well as the caste he belongs to. KL: To me it gets to the question of human beings as individuals and human beings as collective bodies. You lose what distinguishes you when you join this mass but the mass as so much collective energy that you lose yourself to its power. That’s something that you see in his other films, in these party sequences that are alternately fascinating, seductive and terrifying all at once.

KL: To me it gets to the question of human beings as individuals and human beings as collective bodies. You lose what distinguishes you when you join this mass but the mass as so much collective energy that you lose yourself to its power. That’s something that you see in his other films, in these party sequences that are alternately fascinating, seductive and terrifying all at once.

MJR: They’re subsuming, in a way that allows you to lose yourself in a good way and in a very frightening way. Individual freedom versus mass appeal

KL: It gets to Fellini’s own attitude towards individuality. One of the paradoxes of his films is that they’re considered to be among the most ego-driven because their sensibility is so distinctive. He’s the quintessential artist who imposes his vision on the world. At the same time some of the best moments are these mass sequences with dozens of people and you’re lost in the melee of humanity.

MJR: Even though Fellini usually gives us someone to identify -- for example the Marcello character in La Dolce Vita -- in And The Ship Sails On we have a reporter character who’s our surrogate, but we’re still not sure who to identify with. Identification in Fellini films are very transitory -- it varies depending on the situation. It can completely dissolve.

KL: Some might say that this is the weak point of this film, that there’s no strong figure to identify with. There’s no Mastroianni who’s captivating and glamorous, and you identify with him and enjoy him. It’s more along the lines of Satyricon, where you’re adrift among all these wild things going on, and your attitude towards these events is less anchored.

MJR: What’s interesting is that the heroes in Fellini’s earlier films -- Nights of Cabiria…

KL: La Strada… MJR: Those characters give way to these ciphers who we are really not sure how to feel about, or these weak, reporters who are totally undermined and shown to be ridiculous in their claims to objectivity. And that’s what makes their films interesting or risky.

MJR: Those characters give way to these ciphers who we are really not sure how to feel about, or these weak, reporters who are totally undermined and shown to be ridiculous in their claims to objectivity. And that’s what makes their films interesting or risky.

KL: It’s amazing the turn that Fellini made from the romantic protagonists of the 50s and 60s to these anti-hero pieces in the 70s and 80s. Fellini’s reach can be pretty broad. He’s a filmmaker who likes to embrace different people, and he’s encompassing a lot of different roles that people choose for themselves within this realm of music as a reflection of society. Even with the realm of music you establish a hierarchy between these these highbrow trained musicians and intellectuals, and these Serbian folk whose music is as natural as the air they breathe and they don’t contemplate it as deeply as these intellectuals do, nor do they really have to. One thing that intrigues me about Fellini is that one the one hand he’s such a wide-reaching, wide embracing director, I can’t think of any other director who is as in love with humanity in all its variety, especially its facial and physical variety, some of the most memorable faces are in Fellini movies. At the same time, they all risk edging towards caricature. He has this tendency to illustrate people in terms of their types, which can be limiting at times.

History Aestheticized as Spectacle MJR: One thing that’s interesting about this sequence is that in it, music is unifying two distinct classes of people through their love of music and dance and performance. In previous Fellini films -- and And the Ship Sails On came a decade after Amarcord and Casanova -- he shows that spectacle can create communities that are not joined by love or unification but by fear. So in Amarcord, spectacle, Fascist parades and music and so on are used to bring people under the banner of conformity and mistrust. In Casanova, it’s a complete corruption of the spirit and of love, that create these spectacles that are devoid of any cathartic element, that are really for narcissistic purposes. So it’s interesting in this film, made in 1983, a decade after Amarcord, that Fellini’s view had come around again to a more optimistic, more generous appreciation of what spectacle can do.

MJR: One thing that’s interesting about this sequence is that in it, music is unifying two distinct classes of people through their love of music and dance and performance. In previous Fellini films -- and And the Ship Sails On came a decade after Amarcord and Casanova -- he shows that spectacle can create communities that are not joined by love or unification but by fear. So in Amarcord, spectacle, Fascist parades and music and so on are used to bring people under the banner of conformity and mistrust. In Casanova, it’s a complete corruption of the spirit and of love, that create these spectacles that are devoid of any cathartic element, that are really for narcissistic purposes. So it’s interesting in this film, made in 1983, a decade after Amarcord, that Fellini’s view had come around again to a more optimistic, more generous appreciation of what spectacle can do.

KL: History is reconfigured in these operatic terms. This is a fictionalized historical incident, sort of a melding of the sinking of the Lusitania with the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand, and it’s dealt with by Fellini in a heavily operatic manner. At the end, the way the opera singers evacuate the boat, they make gestures as if they’re about to leave the stage, and the stage itself is on the brink of collapsing as if it was the finale of a Fellini opera.

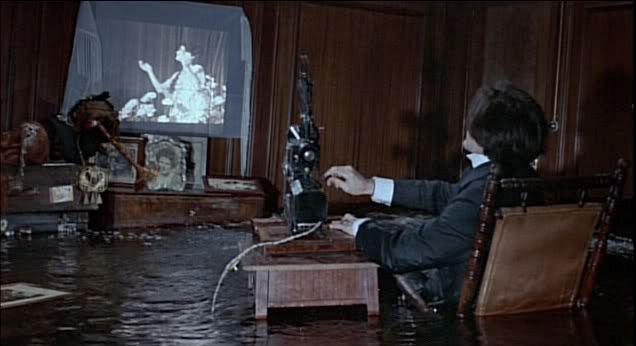

MJR: Everything in this film is highly artificial. The battleship looks unbelievably fake. The sea is made of plastic. And when everyone joins in singing at the end, it’s a climax where the artifice of opera and art renders the historical as an absurd performance piece. And the Ship Sails On is a very pared down film for Fellini in terms of color. It’s very desaturated. Grays and muted greens and blues. And that’s really the palette for the movie. He’s working in very faded tones. The movie starts out in sepia tone and when it goes into color, it’s not like this explosion into color. It’s still very muted. It’s this sort of nostalgic lens through which the film is being regarded. KL: It highly references theater and opera, but at the same time it makes these interesting transitions into cinematic moments,or meta-cinematic moments, where the dead diva is projected on the screen by the conductor…

KL: It highly references theater and opera, but at the same time it makes these interesting transitions into cinematic moments,or meta-cinematic moments, where the dead diva is projected on the screen by the conductor…

MJR: Who’s deeply emotionally attached to her. The whole idea of art as ephemeral, and the technological reproduction of the voice or the image, it’s all a metaphor for the cinema. It’s really Fellini making a statement about cinema through opera in a way. About how artifice almost makes reality both artificial but a greater reality that could ever be lived in in real life.

KL: He’s referencing these artforms that more or less have had their heyday. I wonder if he’s saying the same about cinema. There’s something about this film with its funeral attitude towards cinema… I want to call it a death of cinema film, even as it celebrates cinema’s power -- the penultimate shot in the movie attests to the magic that cinema can construct. Still there’s a sense of profound mourning for the artform as well. Image/Sound/Extras: There once was a time when Criterion packages weren't much to write home about, as evidenced by this lackluster, extra-less disc, first issued in 1999. The non-anamorphic image is grainy (especially in dark scenes); the blues, grays and sepias preferred here by Fellini are more often pallid than luminescent. The mono soundtrack is downright scandalous given that sound and music plays such a heavy part in the film's significance. An accompanying booklet consists of an excerpt from Fellini's autobiography I, Fellini, with scattered musings on the film.

Image/Sound/Extras: There once was a time when Criterion packages weren't much to write home about, as evidenced by this lackluster, extra-less disc, first issued in 1999. The non-anamorphic image is grainy (especially in dark scenes); the blues, grays and sepias preferred here by Fellini are more often pallid than luminescent. The mono soundtrack is downright scandalous given that sound and music plays such a heavy part in the film's significance. An accompanying booklet consists of an excerpt from Fellini's autobiography I, Fellini, with scattered musings on the film.

Video Essay:

____________________________________________________

Kevin B. Lee is a filmmaker based in New York City. He has written for Cinema-Scope, The Chicago Reader, Senses of Cinema and Slant. His website is www.alsolikelife.com.

Michael Joshua Rowin is a staff writer at Reverse Shot. He also writes for L Magazine, Stop Smiling, and runs the blog Hopeless Abandon.

Monday, January 1, 2007

The Criterion Collection #50: And the Ship Sails On

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Hello Kevin and Michael, thank you for your discussion of And The Ship Sails On (ATSSO). I believe you touch on a number of essential topics and I was especially informed by your treatment of the absence of an obvious protagonist in the film with which to identify. At the same time, I found your handling of "highbrow/lowbrow" too vague with respect to the dynamic between opera and the circus that I take to be at the heart of ATSSO. I recently addressed this in my review of ATTSO at Dan Jardine's Cinemania site, which I reproduce here for your consideration. Cheers.

No, this cannot be ranked as one of his great films. But yes, Fellini is never bad. And remembering that it was made very late in his career, ATSSO is fascinating for the fact that he finally focuses on opera. The cultural status of opera in the national psyche of Italy, well, it is an internationally recognized symbol, a flag for the place, a cliché. That opera is absent from the films of the director prior to ATSSO is neither an artistic oversight nor an ideological accident.

It is the circus, of course, that constitutes Fellini's field of consciousness. Not the contemporary big business circus, Cirque d Sole with its safe entertainment for the middle-class; politically domesticated, sexually sanitized, kind enough to leave the tigers in the zoo and hypocritical enough to pretend that they're still free in the jungle. What is informing Fellini is an ongoing nostalgic retrieval of his childhood encounter with the traveling circus of the 1930s, which he recapitulates throughout his work, establishing his own personal mythology of circus theatricality. Hence, for example, in Amarcord the central comedic genius of the film is to treat the coming of the fascist black shirts to his hometown as just another itinerant carnival act. Fellini's circus is dangerous working-class entertainment, politically anarchic, erotically dirty, cruel enough to shine the spotlight on all that is freakish and honest about the grotesque being us and not them.

In contradistinction to this, is there anything more bourgeois than opera? Actually, opera in different times and at different places has been sometimes more and sometimes less elitist and popular. And as already noted from the nationalist perspective, in Italy it has had the full sanction of the state as “common treasure” at least since unification. Fellini's active ignorance of opera was in reaction to mainstream cultural indoctrination, a purposeful negation on his part conducted as a feature of his bohemian development. His eventual attention to opera in ATSSO is an acknowledgment in his mature years that he himself has become an flag of Italian culture, the pride of his country internationally, a subject for doctoral dissertations and all that. Still, idiosyncratic in the extreme, he is no longer iconoclastic for his work is itself iconic.

It is from this position of security that Fellini admits in ATSSO that – hey, you know what? - opera ain't so bad after all. I won't go so far as to say that the film is a sort of apology. It is simply Fellini showing off his new found appreciation for what the rest of his countrymen dogmatically revere. As always, whatever he happens to be dealing with topically he subjects to his weird stylistic concerns, themselves derivative of his circus weltanschauung. This is to say that he shows his appreciation of opera in a very bizarre context.

The eve of WWI setting for the story is a twist on Fellini's own pre-WWII orientation that may or may not have resonance for him. I could not make anything of it dramatically beyond being yet another examination of the “roles and costumes” of the past and I found the storyline of the film a tad boring. What does strike me as meaningful, however, is the spatial designation of ATSSO. The ship setting is not just a plot excuse. The hack metaphor of the journey is beneath Fellini's artistry and besides, his characters tend to wait for Godot, run around in circles, as in a circus. Indeed, the ship setting is a compromise position between the circus and the opera, between being on the move outdoors and being stationary indoors, between a tent and real estate, between a circus ring chalked on the street and the opera-house. What corresponds to this in terms of class should be obvious and following this, I stress that Fellini's ship setting is self-consciously petit-bourgeois.

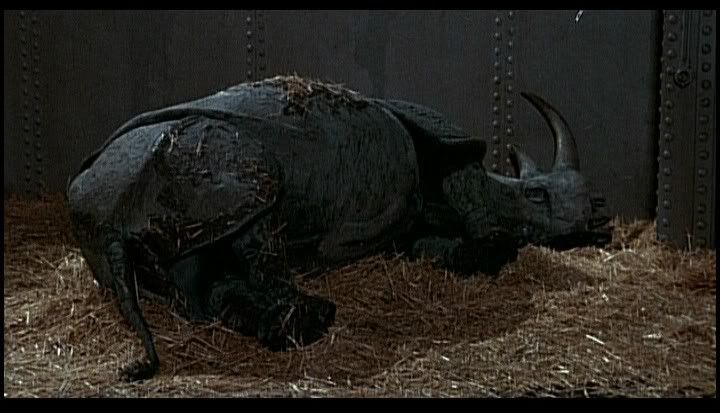

This intermediate class perspective is reverberated in the cordial relations that are struck between the aristocratic passengers and the Serbian refugees. Initially divided in a glaring manner, all it takes is a couple of ethically sensible individuals to make the proper overtures and soon enough the classes are mixing in a celebration of humanity. The opera snobs hit the deck and step to the folk dances of the gypsies. It would be easy to see this as the triumph of the circus but I maintain that Fellini is adopting a centrist position. ATSSO is not a critique of opera. It is an appreciation but one skewed through the prerogatives of the circus. I mean – hello – there's a rhinoceros on board!

In what I take to be the defining scene of the film, the opera stars competitively perform for the labourers down in the boiler room. Here Fellini makes it plain that he is cool with opera as long as he can have it on his own circus-theatrical/ideological terms. Perched on a staircase platform, the singers perform above the workers, literally singing down to them but definitely not singing “down” to them metaphorically. On the contrary, the opera-house as a whole has been turned upside-down and the dirty, sweaty shovelers of coal have become patrons of the arts. Without picking up the tab, no less. At the same time, the highbrow artists have undergone their own reversal. Singing for free like too many buskers on one corner, they are truly absurd, downright silly, belting it out in the most unlikely of places. Fighting to be heard over the roar of the machines, they have entered the realm of the street performer who must contend with all manner of noise. With the possible exception of the rhino being lifted out of the hold by block-and-tackle, the boiler room scene is THE “Felliniesque” moment in the film.

Or could this be the meta-revelation at the end of the film? Uncovering the artifice behind the production, Fellini turns the camera on the infrastructure of the set and the crew operating it. This unmasking may appear unnecessary given how obviously artificial the film is throughout. The sunset is painted and the waves are cellophane and the battleship in the distance is made of cardboard. But for me, it was an effective coda to how the film started. Fellini begins with ersatz black-and-white, jive “vintage” sepia-tone. But behind this supposedly silent footage there is an audio track. We hear the projector running. Already the statement is meta. As ATSSO carries on from here, subjects look directly into the camera to indicate that they know they are being filmed. Once the main film is up and sailing, the central character is simultaneously in the story and outside it, participating in events and commenting on them in asides to the audience. At the end when Fellini rips the lid off entirely, he is unequivocally reminding us that his theatre needs no architecture. He takes down his tent.

Then – Ben

Hi Ben - thanks for re-posting this comment, and yes it's taken me this much time to process a response! Seriously, that's a great account of Fellini's lifelong ambivalence to opera.

Your last couple of lines are evocative albeit ambiguous -- "At the end when Fellini rips the lid off entirely, he is unequivocally reminding us that his theatre needs no architecture. He takes down his tent." Isn't it more that he is acknowledging the architecture of his cinema while simultaneously dismantling it? The last image of the film - the reporter alone in a boat with a rhinoceros in the middle of an artificial sea - may then be seen as an attempt to represent the minimal essence of Fellini's art. Come to think of it , it also shares something in common with the end of CASANOVA with Sutherland alone with the automaton.

Post a Comment