By Robert Humanick For lack of a less obvious metaphor, Berlin Alexanderplatz is like an ocean: vast and deep, for sure, but also internally turbulent, its tides ebbing and flowing, constantly lapping against its barely-there borders. At 15½ hours (divided over fourteen episodes), the film was practically guaranteed immortality in the annals of film history, if only for its length alone. Yet there is far more to appreciate about Rainer Werner Fassbinder's magnum opus than the sheer undertaking of it all, even if its quality wavers throughout, rising and sinking like the tides, some of its moments among the best in cinema and others decidedly more trying.

For lack of a less obvious metaphor, Berlin Alexanderplatz is like an ocean: vast and deep, for sure, but also internally turbulent, its tides ebbing and flowing, constantly lapping against its barely-there borders. At 15½ hours (divided over fourteen episodes), the film was practically guaranteed immortality in the annals of film history, if only for its length alone. Yet there is far more to appreciate about Rainer Werner Fassbinder's magnum opus than the sheer undertaking of it all, even if its quality wavers throughout, rising and sinking like the tides, some of its moments among the best in cinema and others decidedly more trying.

If one is to take the film as a whole -- a challenging act for almost any viewer, given that most of us are accustomed to digesting our art in three or four hour long chunks at a time -- Berlin Alexanderplatz is a sprawling, multi-layered, multi-character study, full of organs and constructs that would seemingly stretch out for miles if uncoiled from their tightly packed arrangements. It is a work representative of what is nowadays being made possible in the union between film and television (of the ever-growing terrain of cinema), fusing the relatively compact, carefully manicured narrative of the feature-length film with the more episodic approach of the television format. Together, the two multiply (rather than simply add upon) their myriad possibilities. Part of me wants to call the film a masterpiece, and, at the very least, there are stretches of work here than can be called something to that effect. It almost goes without saying that the length of the narrative allows for dramatic opportunities otherwise impossible at conventional feature length, with the detail of character here a profound realization of artistic potential that we quickly come to accept and almost take for granted. Berlin Alexanderplatz does so much right -- perfect, even -- that it becomes easy to overlook its successes in light of its more relative "problems." The film is a self-contained smorgasbord of subplots, culs-de-sac and complex character relationships, all vying with the central storyline of Franz Biberkopf's (Günter Lamprecht) re-entry into 1920's Berlin society after a four-year prison sentence (following the inadvertent murder of his lover Ida (Barbara Valentin) -- a traumatic event returned to repeatedly throughout the series, and one whose violence constantly threatens to resurface). Having suffered the consequences for his criminal acts, Biberkopf vows to never again backslide, to go clean and straight no matter what the cost, a promise that leads to tremendous suffering, both of the spirit and of the flesh. Over the course of the film's thirteen parts (and its much-touted two hour epilogue), Franz and those surrounding him will rise and fall, each in their own ways, at once revealing more of their personal selves while also paving a symbolic path towards the rise of Nazism in early 20th Century Germany.

Part of me wants to call the film a masterpiece, and, at the very least, there are stretches of work here than can be called something to that effect. It almost goes without saying that the length of the narrative allows for dramatic opportunities otherwise impossible at conventional feature length, with the detail of character here a profound realization of artistic potential that we quickly come to accept and almost take for granted. Berlin Alexanderplatz does so much right -- perfect, even -- that it becomes easy to overlook its successes in light of its more relative "problems." The film is a self-contained smorgasbord of subplots, culs-de-sac and complex character relationships, all vying with the central storyline of Franz Biberkopf's (Günter Lamprecht) re-entry into 1920's Berlin society after a four-year prison sentence (following the inadvertent murder of his lover Ida (Barbara Valentin) -- a traumatic event returned to repeatedly throughout the series, and one whose violence constantly threatens to resurface). Having suffered the consequences for his criminal acts, Biberkopf vows to never again backslide, to go clean and straight no matter what the cost, a promise that leads to tremendous suffering, both of the spirit and of the flesh. Over the course of the film's thirteen parts (and its much-touted two hour epilogue), Franz and those surrounding him will rise and fall, each in their own ways, at once revealing more of their personal selves while also paving a symbolic path towards the rise of Nazism in early 20th Century Germany.

Not having read Alfred Döblin's 1929 novel of the same name (a much acclaimed literary work, well-remembered, according to my research, for its use of narrative montage over traditional, straightforward storytelling devices), I cannot attest to the faithfulness of Fassbinder's vision. Despite premiering on German television, the film is a work absolutely rooted in the cinema, every setpiece fully utilized not only for the spacial relationships between its characters, but also for the ever-changing perspective experienced by the audience. The style is deliberate, even perfectionist, without ever coming across as forced. Fassbinder waxes his brutal morality play with ravishing use of stage-like long shots and intimate close-ups -- moreso than most works of the cinema, the camera is its own life force here. Doorways, windows, and arches provide the often fragmented, constricted framing through which we routinely view these characters, and so too do these architectural structures bear down on them like the invisible forces of social order that Franz Biberkopf constantly finds himself fighting against. Berlin Alexanderplatz makes the political personal, bearing witness to its characters' slow absorption into the fabric of the Weimar era, each and every one of them half-cognizant players in some larger, unseen plan. Unsurprisingly, Berlin Alexanderplatz shows a general disregard for time, using the narrative form liberally to carve out a distinct emotional and physical "place" which can be occupied by both the viewer and the characters on screen. To go into point-by-point specifics of the far-reaching storyline would be a near-fruitless effort here, but suffice to say that the almost relaxed familiarity one begins to feel towards these individuals after but three or four episodes allows for a newfound level of investment and emotional response, an experience already well-known to many mainstream filmgoers in regards to Peter Jackson's equally indulgent (and to equally positive effect, I would argue) Lord of the Rings films. The opening montage that precedes every episode of Berlin Alexanderplatz (with the exception of the epilogue) acts like something of a perpetual thematic summary, revealing itself as such only as the series reaches its final stages. Set to the industrial chugging of a locomotive engine, it unfurls in sepia-toned glory, a plethora of still images capturing the life and times of historic Germany, with the story to follow but a minuscule chapter amidst the countless stories waiting to be told.

Unsurprisingly, Berlin Alexanderplatz shows a general disregard for time, using the narrative form liberally to carve out a distinct emotional and physical "place" which can be occupied by both the viewer and the characters on screen. To go into point-by-point specifics of the far-reaching storyline would be a near-fruitless effort here, but suffice to say that the almost relaxed familiarity one begins to feel towards these individuals after but three or four episodes allows for a newfound level of investment and emotional response, an experience already well-known to many mainstream filmgoers in regards to Peter Jackson's equally indulgent (and to equally positive effect, I would argue) Lord of the Rings films. The opening montage that precedes every episode of Berlin Alexanderplatz (with the exception of the epilogue) acts like something of a perpetual thematic summary, revealing itself as such only as the series reaches its final stages. Set to the industrial chugging of a locomotive engine, it unfurls in sepia-toned glory, a plethora of still images capturing the life and times of historic Germany, with the story to follow but a minuscule chapter amidst the countless stories waiting to be told.

For me, it is in the details of these stories that Berlin Alexanderplatz shines brightest, with many of its evocations and subtleties among the deepest I've yet encountered in the medium. Among the ever-shifting storyline ultimately emerges a relationship between Franz and the innocent Mieze (Barbara Sukowa), the rhapsody of which is upset not only by Franz's own internal demons and his inability to properly recognize or rectify them, but also a strangely homoerotic friendship with the devious Reinhold Hoffmann (Gottfried John), a character of arguably greater complexity, and whose contradictions of personality at times make him even more fascinating than the more prominent Biberkopf. Although far from the only persons of importance in the film, these three characters make up the self-destructive core of Berlin Alexanderplatz, the id, ego and superego whose impossible yet highly necessary coexistence comes inevitably crashing down (in the finest scene of the entire film, set in a fog-shrouded forest, Mieze and Reinhold engage in a conflict seemingly preordained by cosmic forces). It then remains only for the shell-shocked survivors to make some sense out of this event in its ashen aftermath. It is that aftermath that makes up Berlin Alexanderplatz's highly controversial, much-debated two-hour epilogue, an epic mess (with mess not necessarily being a negative descriptor here) that strikes this viewer as at once exhilarating and excruciating, simultaneously limited by its own lofty ambitions (and the near-impossibility of realizing them in a tangible visual format) and catapulted into some high level of accomplishment by the sheer effort of it all. After the final of many devastating blows to his person, Biberkopf wanders throughout his own hell-infused subconscious, revisiting friends and acquaintances past, trying to find some truth amidst the tarnished world he's become all but oblivious to. Alternating between the real and surreal, this finale is a stylistic indulgence test almost impossible to prepare for, employing literalistic religious imagery and staged setpieces to exacerbating effect -- in part unforgivably cloying, yet also something of a wonder to behold. There are unflourished personal encounters here whose effect goes beyond words, while a boxing sequence sees Fassbinder striking just the right tone between dreamlike enigma and character exposé, although even these do not totally offset the instances of overbearing, practically inane pretentiousness.

It is that aftermath that makes up Berlin Alexanderplatz's highly controversial, much-debated two-hour epilogue, an epic mess (with mess not necessarily being a negative descriptor here) that strikes this viewer as at once exhilarating and excruciating, simultaneously limited by its own lofty ambitions (and the near-impossibility of realizing them in a tangible visual format) and catapulted into some high level of accomplishment by the sheer effort of it all. After the final of many devastating blows to his person, Biberkopf wanders throughout his own hell-infused subconscious, revisiting friends and acquaintances past, trying to find some truth amidst the tarnished world he's become all but oblivious to. Alternating between the real and surreal, this finale is a stylistic indulgence test almost impossible to prepare for, employing literalistic religious imagery and staged setpieces to exacerbating effect -- in part unforgivably cloying, yet also something of a wonder to behold. There are unflourished personal encounters here whose effect goes beyond words, while a boxing sequence sees Fassbinder striking just the right tone between dreamlike enigma and character exposé, although even these do not totally offset the instances of overbearing, practically inane pretentiousness.

The experience of the epilogue is troubling in ways unbecoming to the material, and this suggests that, more than anything in the film prior, the flaws here greatly outweigh the benefits. But this is not to say the film doesn't arrive at an ultimately satisfactory destination. Indeed, Berlin Alexanderplatz is often able to overcome its perceived "flaws" via its own self-devouring, grandiose capabilities, while the effect of its more trying sections hinge on each individual viewer's ability to forgive the film its trespasses. If greatness is determined less by perfection than by sheer forward thrust, I can think of few better examples than Berlin Alexanderplatz. Like its main character -- prone to tangents, violence and complete self-indulgence -- it is a thing of immense beauty. Image/Sound/Extras: This Criterion release could have been entirely without features and it would still rank among the finest DVDs of the year. Taking into account the PAL-to-NTSC-slowdown issue already addressed by Criterion, the 1.33:1 image and Dolby 1.0 mono sound are impeccable: remarkable colors and lush skin tones, the original 16mm grain preserved in a transfer that ranks among the finest I've ever seen. Criterion has chosen to "picturebox" the feature, framing the image in a slight black box so that none of the borders will be lost, depending on the television being used for viewing. (Editor's note: see this review from DVDBeaver for further explanation of "pictureboxing.") Audio is similarly excellent, even if it isn't designed to blow the roof off your surround sound system, Bruckheimer style.

Image/Sound/Extras: This Criterion release could have been entirely without features and it would still rank among the finest DVDs of the year. Taking into account the PAL-to-NTSC-slowdown issue already addressed by Criterion, the 1.33:1 image and Dolby 1.0 mono sound are impeccable: remarkable colors and lush skin tones, the original 16mm grain preserved in a transfer that ranks among the finest I've ever seen. Criterion has chosen to "picturebox" the feature, framing the image in a slight black box so that none of the borders will be lost, depending on the television being used for viewing. (Editor's note: see this review from DVDBeaver for further explanation of "pictureboxing.") Audio is similarly excellent, even if it isn't designed to blow the roof off your surround sound system, Bruckheimer style.

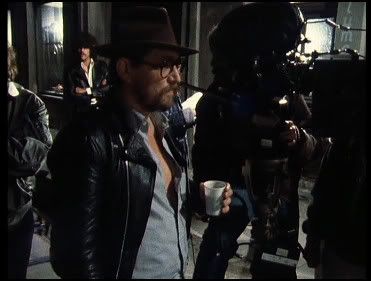

The extras, then, are not unlike whipped cream atop a mile-high meringue pie, although you may need to let the main course digest for a week or three before dovetailing into their excesses. In addition to the epilogue, Disc 6 includes the documentary "Fassbinder's Berlin Alexanderplatz: A Mega Movie and Its Story", in which cast and crew reflect on their work as if recalling some chunk of ancient, almost mythological history. Disc 7 holds the bulk of the bonus material, beginning with the informative "Notes on the Making of Berlin Alexanderplatz", a 44-minute promotional documentary made in 1979 during the shooting of the film. Most interesting here is the opportunity to see Fassbinder at work, a master in complete control and altogether without concern for anything that stands in his way. The half-hour "Berlin Alexanderplatz Remastered" covers the extensive efforts taken to restore the film, while the 23-minute interview with Johns Hopkins University professor Peter Jelavich provides a more singularly intimate deconstruction of the novel and film and their artistic and social importance. Also included is the 1931 film adaptation of the novel, directed by Phil Jutzi and penned by Döblin himself. It is an interesting work caught somewhere between the visionary technical bravura of the late silent period and the constrained medium shots of the early sound era, with Döblin having managed to whittle the essence of his work down into a mere 80 minutes. Watching it post-Fassbinder's version is nothing short of surreal. ___________________________________________________

___________________________________________________

House contributor Robert Humanick's writings have appeared in Slant Magazine and on his blog The Projection Booth. He also works sporadically with fellow Slant critic Paul Schrodt at The Stranger Song.

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

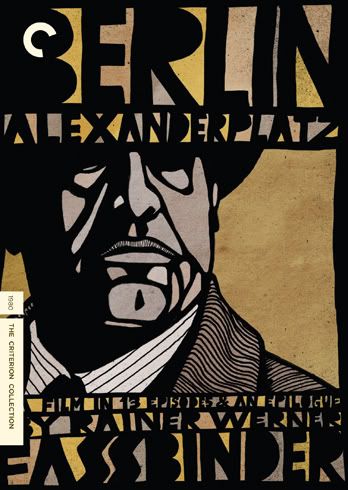

The Criterion Collection #411: Berlin Alexanderplatz

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment