By Andrew Chan Before the average person could afford to travel by air, movies were the most viable form of transportation. Audiences were stunned by how this new medium could convince the eye it was having an intimate encounter with a corner of the world previously inaccessible. It is dismaying, then, to realize that a certain stock of images have always dominated cinema history, and that the art form so rarely lives up to its capacity for introducing new sights and sounds to our worldview. In the 1980s, when the Chinese government granted Bernardo Bertolucci unprecedented access to the Forbidden City, an entire nation that had been ignored in popular world cinema suddenly became a new frontier for Western viewers. The promise of the project must have seemed overwhelming: at a time when good old camp like The Good Earth and Shanghai Express were still Hollywood’s paradigmatic depictions of the country, here was the most sensual of European masters taking on the role of a modern-day Marco Polo. He would come back to share with us treasures that had never appeared before on a movie screen. When the resulting achievement, The Last Emperor, became an international hit and a whirlwind success at the Academy Awards, it was a breakthrough for Chinese images in Western cinema. But behind the silk veils and looming structures of Bertolucci’s biggest blockbuster remains one of the strangest mainstream epics imaginable, a film that wears its compromises of style and perspective on its sleeve.

Before the average person could afford to travel by air, movies were the most viable form of transportation. Audiences were stunned by how this new medium could convince the eye it was having an intimate encounter with a corner of the world previously inaccessible. It is dismaying, then, to realize that a certain stock of images have always dominated cinema history, and that the art form so rarely lives up to its capacity for introducing new sights and sounds to our worldview. In the 1980s, when the Chinese government granted Bernardo Bertolucci unprecedented access to the Forbidden City, an entire nation that had been ignored in popular world cinema suddenly became a new frontier for Western viewers. The promise of the project must have seemed overwhelming: at a time when good old camp like The Good Earth and Shanghai Express were still Hollywood’s paradigmatic depictions of the country, here was the most sensual of European masters taking on the role of a modern-day Marco Polo. He would come back to share with us treasures that had never appeared before on a movie screen. When the resulting achievement, The Last Emperor, became an international hit and a whirlwind success at the Academy Awards, it was a breakthrough for Chinese images in Western cinema. But behind the silk veils and looming structures of Bertolucci’s biggest blockbuster remains one of the strangest mainstream epics imaginable, a film that wears its compromises of style and perspective on its sleeve. Following the life of Pu Yi, who ascended the throne at the age of three, the film’s structure shifts back and forth from his early days as a purely symbolic ruler to his gradual movement away from the palace and later imprisonment in a Communist reeducation center. Doted on since infancy by eunuch servants who obey his every command, Pu Yi learns to live a life of seemingly unlimited privileges, but realizes he is trapped when he cannot even leave the grounds to mourn his biological mother who has died beyond the palace walls. Having never been instilled as a youth with any values other than that of his own (ultimately hollow) importance, he grows into little more than a marker of the times, a vessel for the ideologies he assumes in order to stay in power at least in name. He eventually falls prey to Japan, which establishes him as ruler of the puppet-state Manchuria.

Following the life of Pu Yi, who ascended the throne at the age of three, the film’s structure shifts back and forth from his early days as a purely symbolic ruler to his gradual movement away from the palace and later imprisonment in a Communist reeducation center. Doted on since infancy by eunuch servants who obey his every command, Pu Yi learns to live a life of seemingly unlimited privileges, but realizes he is trapped when he cannot even leave the grounds to mourn his biological mother who has died beyond the palace walls. Having never been instilled as a youth with any values other than that of his own (ultimately hollow) importance, he grows into little more than a marker of the times, a vessel for the ideologies he assumes in order to stay in power at least in name. He eventually falls prey to Japan, which establishes him as ruler of the puppet-state Manchuria.

The challenge of the film is to dramatize the struggle of a man who has little courage or wisdom to impress an audience, a man who was revered in his own cocoon-like remnant of China’s dying feudalist system, and who had only ever possessed the mere image of authority. Bertolucci doesn’t paint a portrait of a sympathetic or passionate person, so he is lucky to have chosen John Lone as the leading man. Playing Pu Yi from young adulthood to old age, and aided by some expert and subtle makeup work, Lone delivers the film’s most emotionally resonant performance by making variations on an unwavering emotional monotone. With more resignation than externalized despair, he manages to shape a character of compelling humanity and compromised dignity, communicating through perfectly maneuvered facial expressions (wounded but never pitiable). The title character is a cipher, but the restrained elegance of Lone’s interpretation helps anchor a film that insists on virtuosity on every sensory level. From the moment it enters the Forbidden City, the film dares us to take in all the beauty Bertolucci has laid out for us. It is as if he believes these long-storied palaces and courtyards were constructed for the sole purpose of being filmed by him. But The Last Emperor is not only a magnificent example of location shooting; it also counts as one of the great collaborations of cinematographer, art director, and costume designer, that relationship which has always been holy in the tradition of epic filmmaking. This is lavishness that doesn’t normalize; there is always something new to be awed by, which may be compensation for the absence of other traditional epic tropes that hook a viewer. There is no sweeping romance to speak of here, and the sex in the film is a collection of recycled gestures from The Conformist. Nor is there any suspense to relish in the film’s political intrigue, nor the epic’s usual expansive sense of space in the sets’ imprisoning enclosures.

The title character is a cipher, but the restrained elegance of Lone’s interpretation helps anchor a film that insists on virtuosity on every sensory level. From the moment it enters the Forbidden City, the film dares us to take in all the beauty Bertolucci has laid out for us. It is as if he believes these long-storied palaces and courtyards were constructed for the sole purpose of being filmed by him. But The Last Emperor is not only a magnificent example of location shooting; it also counts as one of the great collaborations of cinematographer, art director, and costume designer, that relationship which has always been holy in the tradition of epic filmmaking. This is lavishness that doesn’t normalize; there is always something new to be awed by, which may be compensation for the absence of other traditional epic tropes that hook a viewer. There is no sweeping romance to speak of here, and the sex in the film is a collection of recycled gestures from The Conformist. Nor is there any suspense to relish in the film’s political intrigue, nor the epic’s usual expansive sense of space in the sets’ imprisoning enclosures.

Banking on keeping the audience’s attention with the newness of its images, The Last Emperor is caught in the awkward position of having to reconcile its orientalist curiosity with its historical reverence, its markedly Western perspective with its desire to immerse audiences in authentic details of an insular world. What results from Bertolucci grafting his European sensibilities onto these Chinese landscapes? First off, it’s important to discuss the disorienting effect of having a predominantly Chinese cast deliver dialogue almost exclusively in English—an issue that is easier to raise now that a number of recent, popular American movies have been made in foreign languages (Letters from Iwo Jima, The Kite Runner). This choice emphasizes the alien quality that Bertolucci surrounds his characters in; for instance, the youngest versions of Pu Yi that we encounter in the film sound downright supernatural when they open their mouths and deliver the script’s stilted lines in vaguely Chinese-American accents. The strategy is full of pitfalls, and the wheels seem to come off completely when the emperor’s Scottish tutor arrives and, suddenly, the adolescent Pu Yi’s English becomes shakier as if to remind us that this is not his native language. But where a film like Memoirs of a Geisha was offensive for its substitution of Japanese with broken English, The Last Emperor is uncomfortable with a purpose, as it constantly keeps us aware that this interpretation of history is being translated through an outsider’s lens. At the same time, though, this reading of the film reveals one of the deepest flaws in screenwriter Mark Peploe’s writing: rarely escaping the caricatured cadence of their speech, all his characters remain merely conceptual and almost indistinguishable from each other in personality. Language is only one factor in the film’s negotiation of East and West. That struggle is embedded in Bertolucci’s exoticizing gaze, which never fails to relish the details of palace customs, such as a turtle swimming in a bowl of soup or a dance by Tibetan lamas. It is not Bertolucci’s goal to get us acclimated to our surroundings; at times, the Forbidden City is shot like a busily designed sci-fi/fantasy set, turning foreign style into gaudy artifice. But this is a film that makes a case for the exoticizing gaze as a mode native to the movie camera, and for exoticism as a natural interest of the cinema, insofar as the act of filmmaking is tied to the creation of spectacle. In its position in the chronology of film history (predating Zhang Yimou’s 1990 Ju Dou, the first mainland Chinese film to be nominated for a foreign-language Oscar), there is no way for The Last Emperor to dissociate from notions of the “exotic.” But the perspective from which it regards the Forbidden City seems accurate not only to the way foreigners would view it, but also to the way Chinese people are encouraged to view their own history—as a tourist attraction or amusement park—in the wake of headlong modernization. The changes that have occurred in twentieth-century China have occurred at such a speed that it is impossible for the splendors of the past to appear anything but alien to the contemporary experience. In the end, it is a double-edged sword that the film keeps the beast of Chinese history (rather than East-West relations) at the center of its attention. While this focus is a rare achievement for Western cinema, it also seems to have struck fear in the screenwriter, who seems intimidated by his own material, or by all the visual magicians bringing it to life along with him. Instead of offering us some much-needed characterization, Peploe substitutes the kind of existential numbness he brought to Antonioni’s The Passenger.

Language is only one factor in the film’s negotiation of East and West. That struggle is embedded in Bertolucci’s exoticizing gaze, which never fails to relish the details of palace customs, such as a turtle swimming in a bowl of soup or a dance by Tibetan lamas. It is not Bertolucci’s goal to get us acclimated to our surroundings; at times, the Forbidden City is shot like a busily designed sci-fi/fantasy set, turning foreign style into gaudy artifice. But this is a film that makes a case for the exoticizing gaze as a mode native to the movie camera, and for exoticism as a natural interest of the cinema, insofar as the act of filmmaking is tied to the creation of spectacle. In its position in the chronology of film history (predating Zhang Yimou’s 1990 Ju Dou, the first mainland Chinese film to be nominated for a foreign-language Oscar), there is no way for The Last Emperor to dissociate from notions of the “exotic.” But the perspective from which it regards the Forbidden City seems accurate not only to the way foreigners would view it, but also to the way Chinese people are encouraged to view their own history—as a tourist attraction or amusement park—in the wake of headlong modernization. The changes that have occurred in twentieth-century China have occurred at such a speed that it is impossible for the splendors of the past to appear anything but alien to the contemporary experience. In the end, it is a double-edged sword that the film keeps the beast of Chinese history (rather than East-West relations) at the center of its attention. While this focus is a rare achievement for Western cinema, it also seems to have struck fear in the screenwriter, who seems intimidated by his own material, or by all the visual magicians bringing it to life along with him. Instead of offering us some much-needed characterization, Peploe substitutes the kind of existential numbness he brought to Antonioni’s The Passenger.

The Last Emperor stands alongside Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi as a hugely popular ’80s film by a Western director in awe of Asia. Both of these biopics (and their runaway Oscar success) constituted a new kind of prestige picture, one that stroked the viewer’s self-regard by having him re-embrace the outside world but that also encouraged an aloof reaction with an enigmatic figure at its center. That Bertolucci’s film has always been the superior work is not only due to the visual genius on display in every frame. It is also because, in the end, it claims no authority over the history and culture it shares with us. Skimming the surface of the mind-boggling complexities of Chinese history, The Last Emperor can be both criticized and praised for the dissatisfaction it leaves in its audience. This is a film that seeks to engage that suspension of belief required by the most radical social upheavals, to inhabit that liminal space of historical transition. So perhaps it is right that Bertolucci would plant us behind a gauzy curtain rather than on the solid ground of the straightforward epic—even when such honorable distance is at times the film’s undoing.

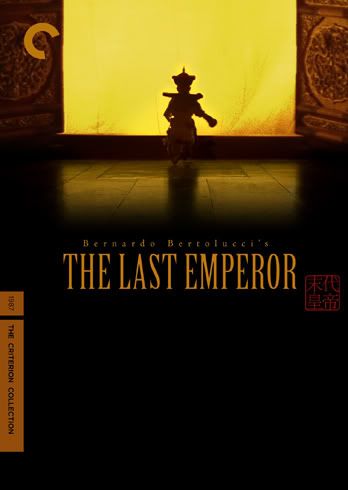

Image/Sound/Extras: It would be hard to imagine a more satisfying treat for a Last Emperor and/or Bertolucci fan than Criterion’s new four-disc package. The company has outdone itself with a level of meticulousness and generosity rarely lavished on a single movie, and it’s difficult to think of a film more appropriate for such a comprehensive treatment. Despite being deeply flawed, Bertolucci’s most widely seen film deserves our continued attention and fascination for the ways in which it foregrounds almost every element of old-fashioned movie magic. Encountering the film in this beautiful edition, one is left with little question as to how it swept all the technical Oscars of its year. Two major issues surround this release. Disc 1 presents the 165-minute cut seen in theaters in 1987, while Disc 2 offers the television version (which is 53 minutes longer). In a statement on the Criterion blog, the DVD’s producer, Kim Hendrickson, corrects the assumption that the TV version is the “director’s cut” (as it has been promoted on the previous Artisan DVD) and shares a correspondence with the director in which he admits to finding the longer cut “not much different from the other one, just a little more boring.” The TV version was originally completed to fulfill a contractual obligation, but Bertolucci has always considered the theatrical release as definitive. Evaluating the two versions side by side, though, reveals what several critics (including myself) have felt: that the longer cut is the richer experience. While it doesn’t add much in terms of narrative (except for additional prison scenes and one minor character) or historical depth, it smoothes out many of the transitions that seem jerky in the theatrical version, and makes certain scenes more resonant simply by extending them.

Two major issues surround this release. Disc 1 presents the 165-minute cut seen in theaters in 1987, while Disc 2 offers the television version (which is 53 minutes longer). In a statement on the Criterion blog, the DVD’s producer, Kim Hendrickson, corrects the assumption that the TV version is the “director’s cut” (as it has been promoted on the previous Artisan DVD) and shares a correspondence with the director in which he admits to finding the longer cut “not much different from the other one, just a little more boring.” The TV version was originally completed to fulfill a contractual obligation, but Bertolucci has always considered the theatrical release as definitive. Evaluating the two versions side by side, though, reveals what several critics (including myself) have felt: that the longer cut is the richer experience. While it doesn’t add much in terms of narrative (except for additional prison scenes and one minor character) or historical depth, it smoothes out many of the transitions that seem jerky in the theatrical version, and makes certain scenes more resonant simply by extending them.

The more controversial point that must be raised about this DVD regards the involvement of Storaro, who overlooked and approved the transfer. As has been discussed in detail already on a number of DVD review sites, the cinematographer has tried to unify the aspect ratios of his films with the 2.00:1 format Univision, which he devised in 1998 out of fear that his images would be compromised on TV screens. I have not been able to compare Last Emperor’s original 2.35:1 frame with this cropped version, nor do I consider myself a strict purist, but—as many film enthusiasts have noted—home viewing has changed a lot in the decade since Storaro raised his concerns. That this legendary cinematographer (certainly one of the cinema’s great living visual stylists) would retroactively mutilate his own compositions is not a choice easily sympathized with, even if his Univision format once seemed a practical solution to a real problem. However, according to Criterion’s most recent statement on the issue, the original aspect ratio was wider than intended, and 2:1 was always Storaro’s ideal. The cropping isn’t likely to distract most viewers, though, since the image quality on Disc 1 seems to me almost flawless (though it is considerably grainier on Disc 2), and the transfer is a vast improvement on the abysmal Artisan release that has circulated since 1999. The last two discs compile an overwhelming array of supplemental material, which together work to dramatize the process of epic filmmaking to greater effect than almost any other set of DVD features I can think of. Four lengthy featurettes cover a wide terrain. "The Italian Traveler" engages Bertolucci the visionary, featuring him philosophizing on the voiceover, and chronicling his movement East after his proposed adaptation of Dashiel Hammett’s Red Harvest fell through. Two other hour-long documentaries (one produced by BBC) follow the making of the film and offer some incredible behind-the-scenes moments, including footage of Gabriella Cristiana discussing editing choices with Bertolucci. The most recent of the four featurettes is a new collection of interviews with the film’s cinematographer, art director, costume designer, and editor, reminiscing in great detail on their Oscar-winning labors. Rounding out the set is a preproduction video of Chinese locations, which gives viewers a portrait of the country as it looked in the late ’80s, and a handful of interviews that provide insight into the historical background and the artistic process behind the film.

The last two discs compile an overwhelming array of supplemental material, which together work to dramatize the process of epic filmmaking to greater effect than almost any other set of DVD features I can think of. Four lengthy featurettes cover a wide terrain. "The Italian Traveler" engages Bertolucci the visionary, featuring him philosophizing on the voiceover, and chronicling his movement East after his proposed adaptation of Dashiel Hammett’s Red Harvest fell through. Two other hour-long documentaries (one produced by BBC) follow the making of the film and offer some incredible behind-the-scenes moments, including footage of Gabriella Cristiana discussing editing choices with Bertolucci. The most recent of the four featurettes is a new collection of interviews with the film’s cinematographer, art director, costume designer, and editor, reminiscing in great detail on their Oscar-winning labors. Rounding out the set is a preproduction video of Chinese locations, which gives viewers a portrait of the country as it looked in the late ’80s, and a handful of interviews that provide insight into the historical background and the artistic process behind the film.

One of the treasures of this set is a commentary featuring Bertolucci, Jeremy Thomas, screenwriter Mark Peploe, and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto. Running the entire length of the theatrical version, the talk could easily have become boring, but the reminiscences from all participants are instead uniformly entertaining. Another gem in the box is an elegant 96-page booklet, with David Thomson’s astute appreciation of the film as exemplary “tourist cinema,” a brief but deeply felt Film Comment article written by Bertolucci, interviews with Ferdinando Scarfiotti and actor Ying Ruocheng, and a piece by Bertolucci’s personal assistant, followed by his shooting diary. What is extraordinary about Criterion’s work here is that the wealth of extras does not overwhelm or overstate the value of The Last Emperor. Instead, it elaborates on what is indisputably brilliant and interesting in the movie (its visual splendor; its reflection of a certain historical and aesthetic moment), and offers a balanced portrait of a kind of filmmaking that is both auteur-driven and highly collaborative.

Andrew Chan is a poet and film critic currently studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the creator of the blog Movie Love.

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

The Criterion Collection #422: The Last Emperor

Labels:

Andrew Chan,

Bernardo Bertolucci,

The Last Emperor

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment