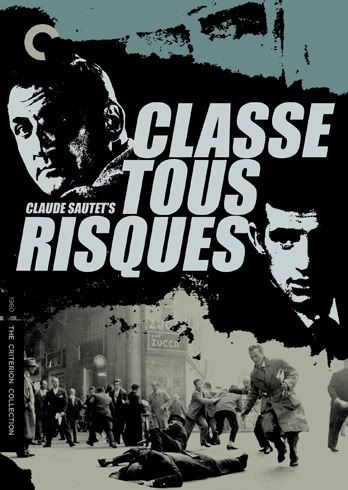

By Andrew Chan Until recently, Claude Sautet’s Classe Tous Risques was a long forgotten noir relic. A commercial flop in its own country, it was only released briefly in the U.S. in a dubbed version called The Big Risk before it fell completely out of sight. But thanks to a Rialto Pictures re-release in 2005, and the attraction of lead performances from stars most consider among the immortals, it has the air of a major new discovery. Following hopeless fugitive Lino Ventura as he sneaks his way from Milan to Paris with wife and children in tow, Sautet’s first major film adopts some of the mood and energy from American crime movies but—like a handful of French films before and after it—tries to endow the genre with a conscience. Responsibility to friends and family humanizes even the most heartless, and Classe Tous Risques takes as its subject the masculine codes of honor that are upheld and broken by those who dare to live outside the law.

Until recently, Claude Sautet’s Classe Tous Risques was a long forgotten noir relic. A commercial flop in its own country, it was only released briefly in the U.S. in a dubbed version called The Big Risk before it fell completely out of sight. But thanks to a Rialto Pictures re-release in 2005, and the attraction of lead performances from stars most consider among the immortals, it has the air of a major new discovery. Following hopeless fugitive Lino Ventura as he sneaks his way from Milan to Paris with wife and children in tow, Sautet’s first major film adopts some of the mood and energy from American crime movies but—like a handful of French films before and after it—tries to endow the genre with a conscience. Responsibility to friends and family humanizes even the most heartless, and Classe Tous Risques takes as its subject the masculine codes of honor that are upheld and broken by those who dare to live outside the law.

The rediscovery of Classe Tous Risques is, in a way, doubly special, as it leads us to reexamine the work of someone who is not an acknowledged master. Sautet’s career is notable for its lack of ostentation. Having begun as a highly respected assistant director in the ’50s, known for fixing the weak spots in a script and taking the reins from inept filmmakers (Truffaut once called him the “mender of French cinema”), he made a name for himself as a skilled and competent craftsman but not as an auteur. Against the two great superstars of the French New Wave, both of whom made their debuts right around the time Classe Tous Risques was released, he had neither the stylistic flair nor the youthful preoccupations to hold his own. What anchored his films was not the nouvelle vague’s cinephilia or ideology, but rather the ordinary human concerns he found at the center of big genre constructions like the criminal underworld or the comic ménage a trois. For him, even the fantasies of genre were subject to the cruel disappointments of real life. I can’t claim any special expertise on Sautet, having only seen the four titles (out of the 14 features he made) currently available on American DVD. But looking back at what I’ve seen of this unsung oeuvre, what strikes me are the affinities linking works as disparate as his first gangster film and the not-quite-romantic dramas for which he later became famous. Consider the lovely César and Rosalie, which was a hit for him in 1972, and the intriguingly understated, mostly unarticulated passion of Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud, which in 1995 became his swan song. Both films introduce an amiable, well-liked man in the autumn of his years falling in love with a young woman. Both are leisurely paced and visually sunny, but also characterized by midlife male frustration. This fascination with aging—with the male’s stumbling transition from one self to another, milder, less free self—can be found in Classe Tous Risques, where Ventura must face up to the responsibilities of a grown man just as the sins of his youth are catching up with him.

I can’t claim any special expertise on Sautet, having only seen the four titles (out of the 14 features he made) currently available on American DVD. But looking back at what I’ve seen of this unsung oeuvre, what strikes me are the affinities linking works as disparate as his first gangster film and the not-quite-romantic dramas for which he later became famous. Consider the lovely César and Rosalie, which was a hit for him in 1972, and the intriguingly understated, mostly unarticulated passion of Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud, which in 1995 became his swan song. Both films introduce an amiable, well-liked man in the autumn of his years falling in love with a young woman. Both are leisurely paced and visually sunny, but also characterized by midlife male frustration. This fascination with aging—with the male’s stumbling transition from one self to another, milder, less free self—can be found in Classe Tous Risques, where Ventura must face up to the responsibilities of a grown man just as the sins of his youth are catching up with him.

In contrast to the sympathy Sautet extends to the men in César and Nelly, the women (Romy Schneider and Emmanuelle Béart) remain about as enigmatic as the trio of female characters in Classe Tous Risques. Defined by the vagueness of their whims, they are gauzily emotional, steely and unknowable, as if Sautet were paralyzed by the thought of having to enter a woman’s psychology. Accordingly, the representations of and attitudes toward love in these films are uniformly ambivalent, and remarkable for being neither condescending to that emotion nor confined by its intensity. When Ventura—almost at the end of his rope—takes time to fall in love with some random chambermaid, the plot twist serves as nothing more than an evanescent moment of grace, requiring minimal dramatization and no further explanation. Even at the end, love is possible, though it is clear it won’t absolve anyone’s sins or compensate for the greatest human weaknesses. While Sautet’s films profess to be grounded in and conflicted over adult fears and dilemmas, there is still something inexplicably remote about them. In César and Rosalie, the lack of intimacy we feel toward the characters allows us to buy into the central love triangle’s frequent and absurd rearrangements. But in Classe Tous Risques’ case, this remove becomes an impediment, keeping the film just out of reach of the ranks of Touchez pas au grisbi, Rififi, and Bob le flambeur, even in the moments when it thrills and moves us. In the effort to avoid melodrama—a difficult act to pull off with those children in jeopardy—it sometimes feels stiff and stifled rather than suave. There is no scene here comparable to the grudging tenderness of Jean Gabin and his best friend sharing a hotel room, or the twinkle in Roger Duchesne’s eyes when he acts as a father figure to a duo of street kids—no scene that gives us a feel for the genuineness of the gangster’s heart of gold and the depth of his family crisis, while also revealing the thug’s capacity for brutishness.

While Sautet’s films profess to be grounded in and conflicted over adult fears and dilemmas, there is still something inexplicably remote about them. In César and Rosalie, the lack of intimacy we feel toward the characters allows us to buy into the central love triangle’s frequent and absurd rearrangements. But in Classe Tous Risques’ case, this remove becomes an impediment, keeping the film just out of reach of the ranks of Touchez pas au grisbi, Rififi, and Bob le flambeur, even in the moments when it thrills and moves us. In the effort to avoid melodrama—a difficult act to pull off with those children in jeopardy—it sometimes feels stiff and stifled rather than suave. There is no scene here comparable to the grudging tenderness of Jean Gabin and his best friend sharing a hotel room, or the twinkle in Roger Duchesne’s eyes when he acts as a father figure to a duo of street kids—no scene that gives us a feel for the genuineness of the gangster’s heart of gold and the depth of his family crisis, while also revealing the thug’s capacity for brutishness.

Ventura is great for his role and instantly relatable, his iconic face exuding more life-size decency than movie-size courage or charisma. But here he is largely incapable of communicating the sorrowfulness of a Bogart or the humor of a Gabin—qualities that make a cliché-ridden genre come alive with inner drama. It is Belmondo, with his mixture of toughness, seduction, and angelic innocence, who emerges as the film’s most alluring element, even as Sautet’s elliptical style keeps the character mostly inscrutable. As the hapless hero’s saving grace, Belmondo (fresh off a star-making turn in Breathless) offers the perfect foil to Ventura. More or less at peace with the contradictory extremes of criminal life, he’s as suave as any of the great men of noir, and separate from all the film’s middle-aged hand-wringing. Sautet’s vision was able to recognize human fragility without turning soft, and was willing to accept the ultimate dissatisfaction in relationships and social life. Where the rules of love fail the characters in Sautet’s later romances, the unforgiving nature of adult society and the irresoluteness of male friendship are what lead Ventura to his inescapable destiny. These darker, more personal undercurrents can easily go unnoticed when Classe Tous Risques is lumped with other pre-New Wave crime flicks, and when César and Nelly are marketed to appeal to the middle-brow tastes Truffaut famously ridiculed in his rants against “la qualité française,” along with the kind of movies that now get exiled to Blockbuster’s foreign section. If a director as subtle and sophisticated as Sautet still fails to inspire much excitement, it’s because he was always, in the words of Jonathan Rosenbaum, aesthetically conservative, even as he tried to breathe new life into tired old formulas. His Classe Tous Risques is not as cold-blooded or urgently told as the finest Hollywood noirs, or as boldly atmospheric as a Jean-Pierre Melville film, or even as entertaining as that wonderful Italian gangster comedy, Mafioso, just recently released on Criterion, which shares the same juxtaposition of the demands of domestic, private life with the relentless pull of the underworld.

Sautet’s vision was able to recognize human fragility without turning soft, and was willing to accept the ultimate dissatisfaction in relationships and social life. Where the rules of love fail the characters in Sautet’s later romances, the unforgiving nature of adult society and the irresoluteness of male friendship are what lead Ventura to his inescapable destiny. These darker, more personal undercurrents can easily go unnoticed when Classe Tous Risques is lumped with other pre-New Wave crime flicks, and when César and Nelly are marketed to appeal to the middle-brow tastes Truffaut famously ridiculed in his rants against “la qualité française,” along with the kind of movies that now get exiled to Blockbuster’s foreign section. If a director as subtle and sophisticated as Sautet still fails to inspire much excitement, it’s because he was always, in the words of Jonathan Rosenbaum, aesthetically conservative, even as he tried to breathe new life into tired old formulas. His Classe Tous Risques is not as cold-blooded or urgently told as the finest Hollywood noirs, or as boldly atmospheric as a Jean-Pierre Melville film, or even as entertaining as that wonderful Italian gangster comedy, Mafioso, just recently released on Criterion, which shares the same juxtaposition of the demands of domestic, private life with the relentless pull of the underworld.

But one trick that Sautet quietly pioneered in both Classe and his later romances is sure to leave a deep impression on anyone interested in taking a closer look at the parallels in his work. His great trademark is a harsh, clipped narrative brevity: deaths and separations and ends of relationships coming so unceremoniously, with so little fanfare, that they show us the swiftness with which life’s changes—and a film’s climax—can occur. In Sautet’s world, as in ours, people depart without warning, without proper goodbyes. And at the end of Classe Tous Risques, Ventura, too, has vanished like an afterthought of the camera, perhaps no luckier or more tragic than the rest of us.

Image/Sound/Extras: The Criterion Collection’s one-disc package boasts a typically beautiful transfer, as well as an impressive collection of excerpts from interviews conducted by French critic N.T. Binh. These include conversations with Sautet, who shares his early experiences in the film industry, and novelist and screenwriter José Giovanni, who relates the true story that inspired him to write Classe Tous Risques. Also included is an old interview of Ventura looking back on his career. Along with the highly informative essays in the set’s booklet—most notable of which is a tribute by Bertrand Tavernier, reminiscing on his double-friendship with mentors Sautet and Giovanni—these supplementary materials emphasize the close bonds forged during the filmmaking process, an insight that complements the film’s focus on the complicated loyalties of male relationships.

Andrew Chan is a poet and film critic currently studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the creator of the blog Movie Love.

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

The Criterion Collection #434: Classe Touse Risques

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment