By Andrew Chan Shortly after making a then-controversial but now little-seen gem named Le Bonheur, Agnès Varda wrote that she had envisioned the film as “a beautiful summer fruit with a worm inside.” More than forty years later, one hears in this statement echoes of Buñuel’s anti-bourgeois perversity, Sirk’s subversion of lush surfaces and narrative clichés, as well as the basis for a whole tradition of American films (exemplified by David Lynch on one end and American Beauty on the other) that claim to expose the demons lurking behind the white picket fence. Then and now, there is a great pleasure in watching forces of chaos and insanity eat away at the glamour of cinema. When Le Bonheur (meaning “happiness”) opens to the carefree strains of Mozart and images of sunlight, sunflowers, and family members hand-in-hand, the contemporary viewer is immediately clued into the joke, having been taught by years of hyper-ironic filmmaking to respond to these symbols with scorn. We can already guess the film is about the tyranny of eternal happiness. What follows is, indeed, a story that demolishes the initial portrait of domestic bliss, replacing it with a version that is cruel and animalistic. But the predictability stops there. The power of Varda’s film is that it remains startling even in our savvy era, leaving us as uncertain and suspicious of its intentions as its first audiences must have been.

Shortly after making a then-controversial but now little-seen gem named Le Bonheur, Agnès Varda wrote that she had envisioned the film as “a beautiful summer fruit with a worm inside.” More than forty years later, one hears in this statement echoes of Buñuel’s anti-bourgeois perversity, Sirk’s subversion of lush surfaces and narrative clichés, as well as the basis for a whole tradition of American films (exemplified by David Lynch on one end and American Beauty on the other) that claim to expose the demons lurking behind the white picket fence. Then and now, there is a great pleasure in watching forces of chaos and insanity eat away at the glamour of cinema. When Le Bonheur (meaning “happiness”) opens to the carefree strains of Mozart and images of sunlight, sunflowers, and family members hand-in-hand, the contemporary viewer is immediately clued into the joke, having been taught by years of hyper-ironic filmmaking to respond to these symbols with scorn. We can already guess the film is about the tyranny of eternal happiness. What follows is, indeed, a story that demolishes the initial portrait of domestic bliss, replacing it with a version that is cruel and animalistic. But the predictability stops there. The power of Varda’s film is that it remains startling even in our savvy era, leaving us as uncertain and suspicious of its intentions as its first audiences must have been.

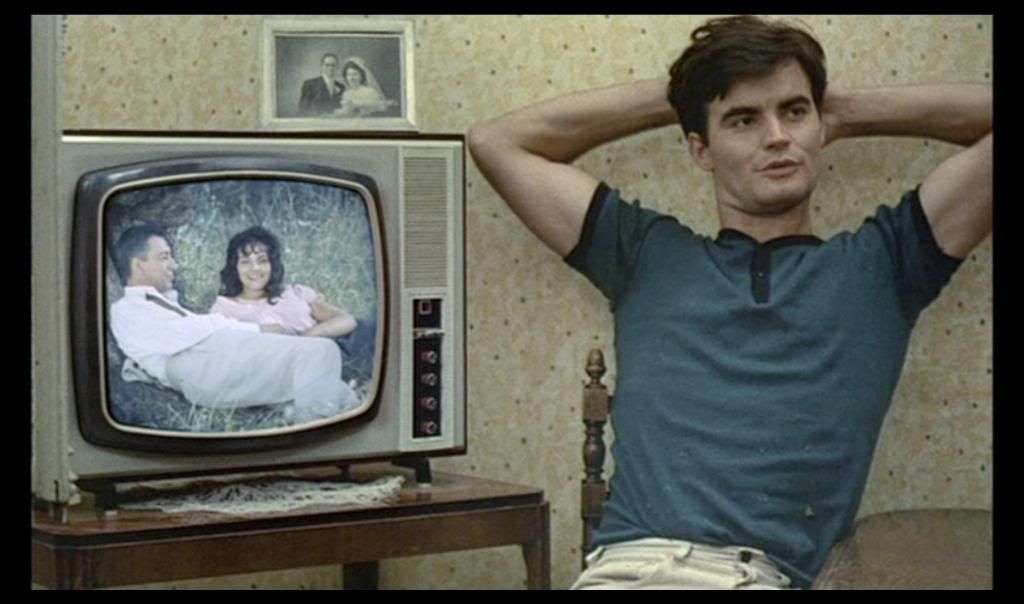

Like the title character of Varda’s 1985 film Vagabond, husband-father-philanderer François (Jean-Claude Druout) disregards the codes that dictate how life should be lived in Western society; the crucial difference here is that he inhabits a world of his own making, and is therefore free from being victimized for his behavior. Early scenes show him frolicking through nature with his two unnaturally obedient children, and sometimes making love to his beautiful wife on a blanket in the grass. When he falls for another woman, he does so with the innocent affection of a boy. He discovers, to his delight and convenience, that the adulterous affair enhances rather than detracts from his marriage, and he expects his wife to approve of the new circumstances. “Happiness works by addition,” he explains. If she is devastated by his admission, you don’t see it for a second on her face; love continues without question, at least until the plot twists toward an inevitable but ambiguous tragedy. Part of the shock of the film is the insular space in which this cruelty occurs. There is no one to condemn François for his charmed life; only we, the audience, can submit an objection. The film buries the rules of moral society so deep within itself that it relies on us to provide those reference points, even as it gets in the way of our doing so. Varda performs a high-wire enactment of the egotistical, patriarchal psyche, taking the world exactly for what it is in the man’s imagination, and unifying so thoroughly with his perspective that his selfishness becomes all the more disturbing. Despite its resolutely sunny disposition, the film—interpreted as pure satire—is as acidic as anything by Catherine Breillat in its depiction of male-female romance, and as delirious in its mixture of sexual openness and sexual humiliation.

Part of the shock of the film is the insular space in which this cruelty occurs. There is no one to condemn François for his charmed life; only we, the audience, can submit an objection. The film buries the rules of moral society so deep within itself that it relies on us to provide those reference points, even as it gets in the way of our doing so. Varda performs a high-wire enactment of the egotistical, patriarchal psyche, taking the world exactly for what it is in the man’s imagination, and unifying so thoroughly with his perspective that his selfishness becomes all the more disturbing. Despite its resolutely sunny disposition, the film—interpreted as pure satire—is as acidic as anything by Catherine Breillat in its depiction of male-female romance, and as delirious in its mixture of sexual openness and sexual humiliation.

But art fueled by contempt alone is likely to run out of steam and, for this reason, what we first see as Varda’s unremittingly ironic tone always threatens to get heavy-handed. To fully appreciate how daring Le Bonheur is, we need to accept that our reading of the film as ironic is, in part, a partisan reaction, one that aligns with a certain side in the ongoing war of sexual mores. Yes, the film is an obvious attack on gender norms that discourage women from voicing their opinions and contradicting men’s desires; Varda sets up a masculine paradise in which lust and love have no emotional consequences, and asks us if we find it desirable. But in the peak decade of the sexual revolution, could she have meant at least some of her questionably utopian vision sincerely? Is François an unexpected hero, a man we should admire for being honest and unembarrassed with his desires? There is no way we can react to the ideal or nightmare presented in the film without revealing our own feelings on the current fads of sexual liberation, on polyamory in particular. But to really engage with the film’s ideas on love, sex, death, and family, we have to entertain the possibility that this version of paradise might somehow, in fact, be desirable. We might ask: If traditional notions of nuclear-family happiness are illusions anyway, then why should the idea of open marriages be so offensive to us? If we recognize that the messy nature of love has been obscured by our overly romantic expectations, then why is it so difficult to accept that multiple, simultaneous loves might be as sustainable as monogamous ones? Are our deep emotions and commitments just falsehoods we use to maintain the artificial separation between the human and the animal? Even as Varda has us consider such questions, her conclusion about this exclusively male fantasy is clear. Whether we view Le Bonheur as dystopian (because its women are interchangeable and disposable) or utopian (because it embraces the full range of human beings’ unpredictable impulses) may, in the end, be immaterial. The film constructs an Eden, a world pre-shame, in which an individual’s feelings are wholly legitimate and never clash with those of anyone else. Varda establishes a vital link between morality and emotion, but the world she has created exists outside of both, and therefore outside reality. One of the most fascinating conflicts that arises in Le Bonheur (a film essentially about denying the existence of conflict) stems from the audience’s unshakable uncertainty of how to apprehend this self-conscious dream world. The film plants itself firmly in the leading male’s psychology, but it never exists in actual (rather than merely conceptual or symbolic) space. The characters are cardboard cutouts who never breathe, let alone choose, for themselves. At times, before its devastating cumulative effect sinks in, the film strikes one as stalling at the level of experiment, never quite making successful art or argument. But what consistently surprises is that, even through Varda’s caked-on style, François’ behavior still manages to unsettle us.

Even as Varda has us consider such questions, her conclusion about this exclusively male fantasy is clear. Whether we view Le Bonheur as dystopian (because its women are interchangeable and disposable) or utopian (because it embraces the full range of human beings’ unpredictable impulses) may, in the end, be immaterial. The film constructs an Eden, a world pre-shame, in which an individual’s feelings are wholly legitimate and never clash with those of anyone else. Varda establishes a vital link between morality and emotion, but the world she has created exists outside of both, and therefore outside reality. One of the most fascinating conflicts that arises in Le Bonheur (a film essentially about denying the existence of conflict) stems from the audience’s unshakable uncertainty of how to apprehend this self-conscious dream world. The film plants itself firmly in the leading male’s psychology, but it never exists in actual (rather than merely conceptual or symbolic) space. The characters are cardboard cutouts who never breathe, let alone choose, for themselves. At times, before its devastating cumulative effect sinks in, the film strikes one as stalling at the level of experiment, never quite making successful art or argument. But what consistently surprises is that, even through Varda’s caked-on style, François’ behavior still manages to unsettle us.

Le Bonheur emerges as a harsh critique of free love, as well as an empathetic exploration of its allure. The film’s visual splendor is both celebratory and elegiac. In Varda’s eyes, nature turns hideous, just like those feelings that (however “natural” to us) reveal our inhumanity. Varda knew something about the eye-candy of Technicolor (as perfected by her husband Jacques Demy in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) and the soft, nostalgic palette of Impressionist painting, both of which she approximates in Le Bonheur’s cinematography. She knew those colors, like happiness itself, could never escape a look of fragility and impermanence: the sense that, with just a bit of rain, they would all wash away. Le Bonheur may be numbered among the many precursors to radical works such as Blue Velvet and Fat Girl, but Varda’s film is moving in ways that a Lynch or Breillat could never be. Even the best of contemporary art dealing with the horror of the quotidian is usually snide and self-congratulatory, and never dares to confront the sweet emotions that can lead us to unintended cruelty, or the ingenuousness with which we harbor our most selfish desires. That good can produce evil, and that the beautiful coexists with the terrible, are facts that the typical movie (at most) only pays lip service to. Varda doesn’t deploy her stylistic audacity in order to disguise a lack of nuance or ambiguity. Even in a film as radically stylized as this, she lets all paradoxes stand so that the most improbable idyll becomes a mirror for our most complicated realities. The summer palette and sunflower imagery might scream irony at first, but it’s not the kind of eye-rolling sarcasm that you can trust or participate in. Instead, it’s disorienting, a trapdoor that opens onto a profoundly uncomfortable moral dilemma.

Le Bonheur may be numbered among the many precursors to radical works such as Blue Velvet and Fat Girl, but Varda’s film is moving in ways that a Lynch or Breillat could never be. Even the best of contemporary art dealing with the horror of the quotidian is usually snide and self-congratulatory, and never dares to confront the sweet emotions that can lead us to unintended cruelty, or the ingenuousness with which we harbor our most selfish desires. That good can produce evil, and that the beautiful coexists with the terrible, are facts that the typical movie (at most) only pays lip service to. Varda doesn’t deploy her stylistic audacity in order to disguise a lack of nuance or ambiguity. Even in a film as radically stylized as this, she lets all paradoxes stand so that the most improbable idyll becomes a mirror for our most complicated realities. The summer palette and sunflower imagery might scream irony at first, but it’s not the kind of eye-rolling sarcasm that you can trust or participate in. Instead, it’s disorienting, a trapdoor that opens onto a profoundly uncomfortable moral dilemma.

Image/Sound/Extras: Perhaps the least-known of the four films in The Criterion Collection’s 4 by Agnès Varda, Le Bonheur comes to us in vibrant color, gorgeously restored; as we learn from one of the disc’s many supplements, the film had to be reconstructed because the 1963 Eastman negative had gone completely pink and beige. According to Varda, who makes several charming appearances throughout the box-set and is listed as “Consulting Producer” in the DVD credits, this version looks identical to the original. Two featurettes consist of reminiscences by the cast on the film's production and reception. In an interview with the lead actresses Claire Drouot (the real-life spouse of Jean-Claude Drouot) and Marie-France Boyer, we learn some heartfelt, down-to-earth lessons on matrimony. Drouot, who after almost 45 years is still married to the film’s star, offsets Le Bonheur’s sharp satire with some practical advice: “There’s no user’s manual. [Marriage is] a craft, it’s like knitting. You take two needles, and you knit. That’s all.” In another short piece, Jean-Claude Drouot—now scruffy, broad, and deep-voiced—returns to the setting of Fontenay-aux-Roses in southwestern France to speak with locals who remember witnessing the film in production. Also included in the package is some black-and-white TV footage chronicling the making of Le Bonheur, during which we catch a glimpse of Varda in the director’s chair sharing a few words with her husband, the great Jacques Demy.

Two featurettes consist of reminiscences by the cast on the film's production and reception. In an interview with the lead actresses Claire Drouot (the real-life spouse of Jean-Claude Drouot) and Marie-France Boyer, we learn some heartfelt, down-to-earth lessons on matrimony. Drouot, who after almost 45 years is still married to the film’s star, offsets Le Bonheur’s sharp satire with some practical advice: “There’s no user’s manual. [Marriage is] a craft, it’s like knitting. You take two needles, and you knit. That’s all.” In another short piece, Jean-Claude Drouot—now scruffy, broad, and deep-voiced—returns to the setting of Fontenay-aux-Roses in southwestern France to speak with locals who remember witnessing the film in production. Also included in the package is some black-and-white TV footage chronicling the making of Le Bonheur, during which we catch a glimpse of Varda in the director’s chair sharing a few words with her husband, the great Jacques Demy.

Perhaps the most interesting extra feature is a 15-minute discussion among a diverse gathering of French intellectuals who either remember seeing the film upon its release or have just encountered it recently for the first time. The comments are not always enlightening, but their exchanges evoke a time and culture in which art films were seen as instigators of philosophical discussion. It is surprising to hear some suggest that Le Bonheur is not a completely mordant comedy, and that it might have its share of genuinely utopian values.

Most inconsequential and irrelevant among the extras are two shorts on the general meaning of happiness, in literary history and on the streets of contemporary France. Most valuable, by far, is the inclusion of Du côté de la côte (1958), Varda’s wonderfully cheeky 25-minute travelogue of the French Riviera. Along with 2000’s The Gleaners and I, this short demonstrates Varda’s gift for inserting playful imagery into a genre as traditionally sober as the documentary. The film, like all her best work, shows her preference for a complex, pliant tone that can express her whimsy, outrage, and melancholy.

Andrew Chan is a poet and film critic currently studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the creator of the blog Movie Love.

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

The Criterion Collection #420: Le Bonheur

Labels:

Agnès Varda,

Andrew Chan,

Le Bonheur

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment